Yumna Kassab

Subscriber Only Access

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Accessibility Tools

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

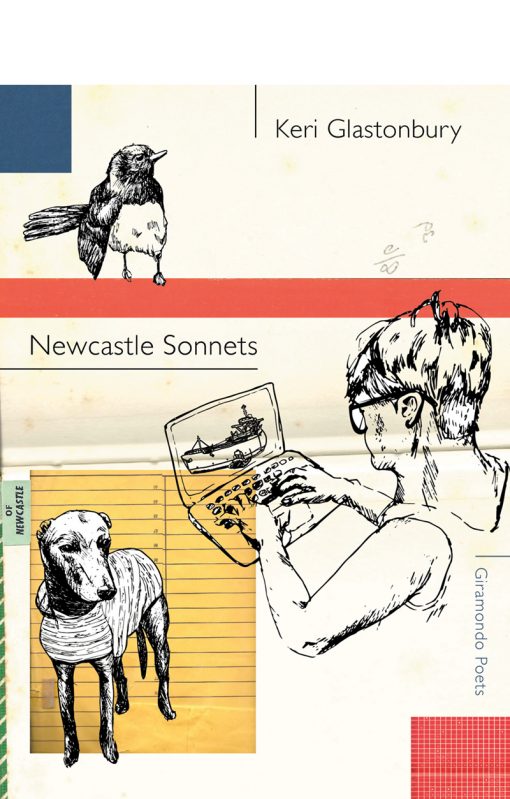

Newcastle Sonnets

Newcastle Sonnets

By Keri Glastonbury

Giramondo

ISBN 978-1-925336-89-4

Reviewed by ERIN MCFADYEN

Keri Glastonbury’s Newcastle Sonnets are at their most mimetic when firing off their dazzling one-liners. The collection is interested in the processes of de- and re-composition that make up, continually, the post-industrial suburbanscape of Newcastle. Taking the city as a kind of monkey-bars apparatus for throwing together and for tumbling apart, the Sonnets treat language the same way as the landscape. They revel in the (re)generative potential of double-meanings, puns, and hyper-specific referentiality, but also, in the end, searing take-downs of local teens and late capitalism alike, delivered with a glimmer to the gut.

The weirdly quick, mercurial march of gentrification is right at the centre of Glastonbury’s target. There’s certainly a pleasure in the poet’s sharp wit, if not an entirely easy one for readers complicit in enjoying her knowing ivory tower in-jokes. Glastonbury might, for example, follow the humour of recognition, in passages like

There are still flashers at bus stops

but now the grapevine is virtual

& kids have Fjällräven Kanken backpacks

in candy colours

with wonderful pastiche puns:

The unbearable lightness

of rail (34)

These lightnesses, slightly unbearable though our delight in them may be, are fast hits of readerly reward. Often several times over in each sonnet, we’re given viscerally indulgent lines like ‘What is Batman’s guilty pleasure? / Clive Palmer’s soft, shitty body,’ (35) or ‘the thick oatmeal / of Sandliands’ face’ (8). We can smile, satisfied, at jokes overlaying the literary and the local — ‘Tess of the Erskinevilles’ (7) — and at speculative questioning with one foot in the university and the other in the clouds: ‘what if John Forbes had lived / to live tweet during Q&A?’ (6).

These moments offer us something like shining hard lollies of poetry, sugar hits immediately delicious on the tongue. It’s tempting to suggest that they puncture, redirect, or interrupt what Glastonbury elsewhere describes as a Novocastrian ‘ambient attention’ (4). We can consider that they give us all of our reward at once, a high-energy hit; the laugh, the immediate vision of reference points coming together. Conversely, we can also think of them as spilling our attention outwards, simultaneously in all the directions of the poet’s many gestures: across landscapes, across literary history, across registers and experiences both haptic and intellectual. In both ways, these joyfully — and, yet, not uncritically — hilarious poems lean into the kind of attention deficit that Glastonbury describes in ‘2 Hours South’:

A farrago of ways to be jealous, ways to be vicarious

ways to suffer, swiped away like old screens (71).

And, yet, to pin these poems as insufficiently attentive would be misrepresentative. Indeed, there’s a way in which they’re exactly the opposite; Glastonbury’s investment in the particularities of the ‘little big smoke’ of Newcastle signals a poet invested in deep attentiveness. Indeed, Glastonbury is critical of views of regional life which deal in broad strokes, in cliché, or in snobbish selectivity. In ‘The White Bird,’ for example, she’s unimpressed that

The metropolitan critic comes to town

& goes only to the regional gallery

— a poetry of complaint, misses the authenticity

of the drying paint. The blacks,

the Prussian Blues (72).

There is certainly a will to recenter the regional in this attitude and in the poems which enact it, positioning Newcastle the minor metropole not simply as secondary or merely aspirational, but as real and affecting and deserving of references that Melbournians might have to Google to get.

Attentiveness to these kinds of details, these minutiae, might be a kind of love. This would be fitting, perhaps, given the nominally generic form of the pieces here — I mean, given that these poems refer to a history of, and are, sonnets. The most obvious point of reference here might be Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, which Glastonbury mines and mimes in poems like ‘Just Quietly Babe.’ Glastonbury’s opening line here — ‘Dear Hamish, hello. It is 5.15am. / Guess we’re more West Coast…’ (29)— walks behind the eminently East Coast Berrigan, whose second sonnet begins ‘Dear Margie, hello. It is 5:15 a.m’ [1]. Equally explicit, though less exegetical, is Glastonbury’s gesture to Shakespeare in ‘The Pink Flamingo (of Trespass).’ In this instance, ‘the Tromp family’s psychedelic road trip / unfolds like a Netflix folie a deux / as Shakespeare’s Sonnet 127 is read in Noongar’ (67). Sonnet 127 is the first of Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’ sequence. Here, double meanings help to figure an ostensibly unconventional object of love:

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were, it bore not beauty’s name;

But now is black beauty’s successive heir,

And beauty is slandered with a bastard shame:

For since each hand hath put on Nature’s power,

Fairing the foul with Art’s false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name, no holy bower,

But is profaned, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress’ eyes are raven black,

Her eyes so suited, and they mourners seem

At such who, not born fair, no beauty lack,

Sland’ring creation with a false esteem:

Yet so they mourn becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so. [2]

If ‘beauty’ comes apart from ‘fairness,’ (as in lightness) here, and attaches itself instead to the raven black of the apostrophised woman’s eyes, ‘fairness’ becomes a truly polyvalent term. Both beautiful and opposed to beauty — because it is the opposite of darkness — fairness’s ambivalence is its foundational feature.

Glastonbury’s gesture to doubleness fits her approach to the sonnet form itself. Even with her clear references to the sonnet in its various historical guises, she’s interested in challenging precisely what this form can do, and what it can reasonably ask poets to do. We might configure her use of the form using Berrigan’s phrase, imagining these works as ‘Poem(s) in the Modern Manner’ [3]. The poems in Newcastle Sonnets are 14 lines long, getting us over the line for formally recognisable Elizabethan sonnets, but rhythmically and in rhyme (as well as in geography, in topography, in politics) we are a long way from London. Her treatment of the sonnet shortens and stretches out the lines, swings the rhythm. So considered, Glastonbury can be seen as, at times, crafting an exposed-brick iteration of this historical form, drawing attention to its structural foundations if only to ironically distance herself, and the aesthetic she ends up with, from them. In this, she makes the sonnet something exciting and relevant for the kinds of readers she might teach in her ‘cushy lecturing job in a regional town’ at the University of Newcastle:

…an anthroposcenester, the full cast

of Girls in every class, like every town

has a Kurt Cobain… (77)

Yet, exposed brick doesn’t always signal the fresh, the new, or the thrilling for Glastonbury, who also sees ‘the pebblecrete poles of the East End / speaking to an historicist melancholy’ (11). Indeed, in ‘The Sea Folding of Harri Jones,’ Glastonbury pictures stone not so much as reconstruction, but as ruin:

Someone’s doing parkour on the military ruins,

no one is washing up in Shepherds Hill cottage,

the ghost of artist-in-residence past… (56)

Looking back and documenting decay — as well an enacting it formally, in protracted blank space and grammatical cul-de-sacs — is always at the centre, then, of Glastonbury’s vision of the gentrifying city, and the new sonnet that she writes it in. For this reason, I want to offer the possibility of reading Gastonbury’s attention to Newcastle not only as ‘ambient,’ but also as meaningfully ambivalent. These aren’t poems written by a ‘metropolitan critic,’ but nor are they really poems of home. Glastonbury, indeed, has commented publicly on her arrival in Newcastle as an adult, and her dual senses of intrigue and distance from it at this time [4]. Hers are poems which register decay and hold gentrification in contempt, while still revelling in the vibrancy of locality, sparkling with gleefully specific references, in a voice that might almost sound proud. Perhaps Glastonbury formulates her own attitude most aptly: Newcastle Sonnets feels ‘post-celebratory’ (71), deflating the glamour of new money and construction, but also finding reparative feeling in the forgotten corners of a city living in the shadow of its historical self:

From below the bridge the neon reflections could be koi,

everyday rewards glimmering in karmic glissando (41).

Notes

1. Ted Berrigan, ‘II,’ in The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, by Alice Notley, with Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan (Berkley: University of California Press, 2005), p. 3.

2. Colin Burrow (ed.), The Complete Sonnets and Poems (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 635

3. Berrigan, ‘Poem in the Modern Manner,’ in Collected Poems, 6.

4. Jim Kellar, ‘Newcastle poet minces no words capturing a city in transition,’ Newcastle Herald, 19 August 2018.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Janette Chen is a Chinese-Australian writer from Lidcombe. She is a member of Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement and the 2019 winner of the Deborah Cass Prize.

Janette Chen is a Chinese-Australian writer from Lidcombe. She is a member of Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement and the 2019 winner of the Deborah Cass Prize.

Wall of Men

Every time mum starts the car, Teresa Teng starts singing. Mum’s 80s Chinese pop ballads blare from the stereo as we pull out of the driveway. Mum is driving me to Lidcombe train station so I can trek it to Veina’s house in Turrella. Outside it’s so hot the heat makes the fibro walls our house look wobbly. I put the windows all the way down because we never use the air con. Teresa Teng’s voice drifts down the street from our car. She sounds so sweet even when she’s accusing her lover of lying to her. As we drive, Mum asks me if Veina has a boyfriend yet. Mum’s face looks dry and red from the heat. She has so many red hairs now, which are white hairs dyed with henna she bought from the Arab shops in Auburn. She glances at me as we slow at a red light and turns off the music. Since I finished high school two months ago, Mum has asked me four times already if there will be any boys when I go out.

‘No, Ma,’ I sigh as we start moving again. It was technically true. As far as I knew, Veina is texting a guy called Andre and hanging out with some guy called Jason but she’s never called either of them her boyfriend.

‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ she asks in Cantonese.

‘Noooo, Ma,’ I groan. Mum flicks her black eyes at me and then back at the road.

‘I was the same age as you are now when I first got married,’ she says. ‘Your Ba is not my first husband.’

I hold my breath. This is the first time Mum has told me about her first marriage but I already know. I overheard her talking to Dad in the kitchen once about a fortune teller she saw back in Guangzhou when she was 17. ‘He told me I would be married twice and he was right about that,’ I had heard her say. In traffic, we inch past an empty lot of weeds and rubble that is fenced off with a glossy sign advertising new apartment blocks. ‘I was so in love with my first husband,’ Mum says. ‘But one day he started locking doors. He started swearing at me. When he slapped me, I thought it would only be one time.’

My muscles tense up when I imagine Mum being hit. We pass the Korean BBQ restaurants on the turn into the station and Mum parks crookedly in the drop-off zone. She keeps talking, her words spilling out like water. ‘He dragged me across our bedroom and strangled me until I realised that if this man loved me he would kill me with his love.’ I put my hand on Mum’s shoulder. I don’t know what else to do with this information. Mum brings her hand to mine and holds it tightly. ‘I know you’re a smart girl. But just be careful. The man you choose is the life you choose.’

Some dickhead in a white ute blasts his horn and cuts Mum off at the end of the sentence. I grab the plastic bag of cherries I’m bringing to Veina’s and tell Mum that I won’t be home for dinner.

On the train to Turrella, I sit in a three-seater behind a young Nepalese couple. The woman’s head is nestled in the space between the man’s shoulder and his brown ear. I think about how I used to see my parent’s wedding photo all the time as a kid. It was propped on the dresser in my parents’ bedroom. The man in the photo was my dad. The woman in the photo had skin as pale as the moon. Yi yi, I had called her, which means Auntie. I couldn’t believe it was my mum. This is because in real life, mum’s skin is the colour of wholemeal bread with lots of seeds in it. In real life, her lips are more brown than red. I knew so little about this other life she had before that photo was even taken.

I get off at Central and change platforms for the airport line. I had never heard of the suburb of Turrella until Veina moved there. Veina is my only high school friend who moved out of home immediately after graduating. Now she lives with four housemates and they all share one tiny bathroom. ‘Fun fact: The Streets ice cream factory used to be in Turrella,’ Veina said when she first told me she was moving. I believed the fun fact, I just couldn’t believe she was moving so far from Lidcombe, away from me. The afternoon heat wraps around me like a blanket when I step off the train. I am the only person standing on the platform. The plastic bag of cherries sweats in my hand.

Veina’s house is a long pink rectangle on a concrete block with a brown roof. When I arrive at the house, I’m sweating from my pits. I tap on the window of Veina’s room but when I get to the front door, it’s her housemate Peter who opens it.

‘Hello,’ he nods. Peter’s tiny head at odds with his massive shoulders. He steps back and holds the door for me. The thin white t-shirt he is wearing is stretched out around the collar and the skin around his neck is pale and pink. All I know about Peter is that he’s a backpacker from Slovakia. And he’s a prawn. He has a body good enough to eat and a head you can throw away. I realise Peter’s holding a big plastic rubbish bag and quickly step inside as he steps out.

The front door of the Turrella house opens straight into the living room with all its random old furniture, plus the sleek black chair Veina and I carried straight out of the new food court in Town Hall one time. I take off my sandals at the door. The pale blue tiles are cool beneath my feet but I know they’re dirty. I can see the dust and hair and dried boogers on the floor. The living room extends into the kitchen on the right, both overlooking the backyard where the laundry is still flapping on the lop-sided Hills Hoist.

Veina’s in the kitchen wearing a big faded black t-shirt with her hair is all over the place. She looks as if she only woke up a couple of hours ago and hasn’t gotten changed yet. Her kitchen is made up of custard coloured plastic laminate cupboards and drawers with golden brown trimmings. Veina gets me started on cutting up onions for our dinner: slut spaghetti. We started calling it that in Year 8 Food Tech because boiling pasta is easy. As I’m tossing onions into the hot pan, Veina tells me about the date Peter brought to the house the night before.

‘He was cooking chicken for this tiny Asian chick and was getting her a chair and everything. But it was like, all so he could fuck her,’ Veina says dryly. When she’s not wearing makeup, Veina looks like she’s fourteen but when she opens her mouth, her voice sounds like she’s smoked a pack a day for as long as she’s been alive. Today, Veina has a thick line of black gel eyeliner painted over her eyelids.

As I pour the contents of a jar of pasta sauce into a saucepan, Veina dumps a handful of oregano and the good bits of a green capsicum we found going soft in the fridge. ‘I always see him looking Asian chicks up and down and up and down,’ Veina says.

‘I would be looking him up and down and up and down if I lived here,’ I confess. But then, I imagine making out with him with his big nose sticking into the side of my face. His mouth would be dry and floury and his pale, slippery body would be squirming on top of mine, crushing me under a mattress of muscle. The thought of it makes my throat tighten.

Peter comes into the kitchen wearing only a pair of baggy track pants. The t-shirt he was wearing earlier is gone. I wonder if he just heard what I said and if all this skin is an invitation. I decline by only looking at him above the neck. His face is long and small in proportion to his wide shoulders and thick neck. His nose sticks out like an arrow. But then he goes to grab a Coke from the fridge and the long line of his back smooths and stretches.

‘Time to eat out this slut spaghetti,’ Veina says after putting the final touch: chilli flakes. In addition to being easy, slut spaghetti needs to be hot. Veina uses chopsticks to put the pasta into two bowls for us and we take them to eat outside.

I have one foot out the front door when it sounds like Peter is saying, ‘Hey, Jen, Jen, Jen, come back.’ His voice is deep and nasally. I turn around. Peter is standing right in front of me. His collarbones are at my eye level and they look like small, featherless wings that spread beneath his skin.

‘You forgot this,’ he says and hands me a fork.

‘Thanks,’ I say to the fork and hurry out the door after Veina.

The front yard is a concrete slab with an old single mattress on the floor. I brush off the dirt and dried leaves and sit down on the mattress next to Veina, leaning my back on the pink stucco exterior of the house. The air around us is starting to cool but the wall is warm against my back. Veina hands me a pair of chopsticks and starts slurping at her spaghetti, her head of black hair bobbing over her bowl. I put Peter’s fork on the floor beside the mattress.

A pair of lanky teenage boys walking a St Bernard are the only people out on the empty suburban streets. The long, pale arm holding the leash looks like a noodle stretching with every step the dog takes. Veina swallows her spaghetti and whistles at the boys. One of them turns around to look at us. He has dark eyes and hair and his skin looks warm and buttery. He might be Eurasian or it might just be the way he looks in the sunset.

‘You shouldn’t do that,’ I tell her.

‘They’re cute,’ Veina says, holding up her hand in greeting. She turns and grins at me. The liner around her eyes makes them look like black crescents with eyelashes.

‘Don’t worry, I know you’ve got it in you,’ Veina says. ‘You just need to be pushed out of the nest. Then you’ll fly like the skank bird you truly are.’

I roll my eyes and watch the boys walk away. In high school, Veina and I cut out all the pictures of cute boys from university brochures and stuck them on the wall in our Year Twelve common room. ‘So Many Opportunities at University’, the caption read. It was Veina’s idea. We called it the Wall of Men, and it was opposite the Wall of Ramen where we pinned up empty instant noodle packets. During our free periods, Veina smoked out the windows of the spare music rooms and I did maths practice papers next to the Wall of Men. The boys in those pictures all had smooth, white skin and were smiling straight at me.

Veina and I went to Sydney Girls High School, an uppity institution for Asian overachievers. Our school motto was ‘Labor Omnia Vincit’, which is Latin for ‘Homework Always Pays’. It was the motto of my mum and the mums of one thousand black-haired teenage girls pressing textbooks to their chests. The ATAR we got was the life we got. I stared back at the boys on the Wall of Men and wondered if they would still be smiling when I beat the living shit out of them at the HSC.

Now that we finished school, me and Veina are melting into lazy flesh bags in the summer. We move from the dirty mattress when the mosquitoes start to bite. Back in the house, the last light is coming through the kitchen window. I wash the cherries I had brought and inspect them under running water. They’re plump and brown and cold from the fridge. A lot of them are scarred or bruised or overripe. Dad had bought a big box of cherries for ten dollars at Flemington markets and my family has been eating cherries at home every night. I pick out a dodgy one, bite out its open sore and put the rest of the cherry in my mouth. It’s so sweet and so cold.

In the living room, Veina turns on the TV to watch If You Are the One on SBS. It’s starting to get dark now, but no one has bothered to turn on the lights. I join her on the lumpy brown couch. A new male contestant steps out of the single-man cylinder that lowers Chinese bachelors to the stage like a love delivery chute. He’s buff with tanned skin. Beijing Beefcake.

Veina and I give the male contestants a score from one to ten depending on how likely we would go on a date with them. We have different selection criteria to the female contestants date to get married. The women on the show want to know if the man has an apartment, a car and a high-paying job. The men want to know what the women look like without any makeup on. Veina and I heckle the television when the contestants talk that shit, which is every episode. We’re going to get our own apartments, cars and high-paying jobs. We don’t do maths practice papers because we like maths.

On screen, Beijing Beefcake smiles and waves at the audience as he walks out of the man capsule and on to the stage. The fabric of his white shirt strains against his pecs.

The back door opens with the broken flyscreen flapping around and Peter steps inside, hulking a basket of laundry against his bare chest. Veina offers him some cherries and Peter puts down his laundry and slides down the armrest of the couch. Now I’m sandwiched between him and Veina. I shift in my seat so we’re not sitting so close. My body thinks it wants one thing but my mind is in control. Don’t throw away the head for a prawn.

We all watch Beijing Beefcake’s pre-recorded video of his life as a personal trainer. I pick out a handful of super soft cherries with wide, open sores dried into dark scabs. I’m feeling stiff from sitting next to Peter. His abs look like skinless chicken nuggets set into two neat rows. They cuddle and curl against each other as Peter leans forward to spit a pip into the bowl. I look away when something starts buzzing beneath me. It’s Veina’s phone, half submerged in the crumby gap between the sections of the couch, vibrating deeper into the fold. I slip my fingers between the couch cushions and grab the phone.

‘Ugh, sorry,’ Veina says. ‘Mum calls every day to check on me.’ She answers the phone with a, ‘Wei’ as she walks off towards her room.

I move over to where Veina had just been sitting so there’s more space between me and Peter. He sneezes. His hands go from covering his nose to stretching across the back of the couch, bridging the distance I had just created between us. It’s cooling down. He needs to put a shirt on. On If You Are The One, Beijing Beefcake is sitting in his living room in a white singlet. I would give him a 6.8. Maybe 8 if he looked a little less inflated. He could be a 9 if he talked about something besides his muscles.

‘My big muscles give me big responsibilities,’ the yellow subtitles at the bottom of the screen translate as Beijing Beefcake nods at me through the television. ‘I swear to the whole nation I would never hit a woman. I can look after her and protect her,’ Beijing Beefcake says. He flexes one bare, bulging brown arm after the other. ‘She can kiss my biceps every day.’

Next to me, Peter shifts in his seat. I hope Veina will come out of her room soon so I don’t have to be alone with Peter. I stuff my mouth with three cherries and sink back into the sofa and stare at the TV. What would it feel like for his strong arms to hold me gently? As I imagine the tenderness of resting my head against his chest, a sharp pain shoots through my mouth. I hold my cheek with my head turned away like I had just been slapped. It feels like someone had cut the right side of my cheek with a pair of scissors. I lean forward and let the contents of my mouth drop into my other hand. The living room lights turn on.

‘Fuck your dad,’ I curse. ‘Oww.’

‘Are you okay?’ Peter says, putting his big, warm hand on my shoulder. It feels heavy there. I look up and see Veina walking across the room.

‘My dad says that when you bite yourself it’s because you’re not eating enough meat,’ she says. ‘Your mouth wants meat in it,’ Veina wiggles her eyebrows suggestively.

‘Ugh, well fuck your dad too,’ I say. I look down at the half-chewed cherries in my open palm. The wet, red flesh glistens like mashed and bloody brains.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.