Samantha Trayhurn reviews Traverse by Tineke Van der Eecken

Subscriber Only Access

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Accessibility Tools

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

We were thrilled and honoured to have participated in an exciting, free public event at the World Literature and Global South Conference (23-25 August, 2019) co-hosted by Peking University and the School of Languages at the University of Sydney, convened by Professor Yixu Lu.

The Global South Salon is a creative submersion into the colloquium themes from diaspora writers and translators who live and work in Sydney, and whose ancestries trace to the Global South. They have lived in the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Africa, Mexico and Australia. They share resistant imaginaries.

The writers were introduced by Dr Toby Fitch with a brief introduction by award-winning poet Dimitra Harvey.

Featuring six award winning writers: Mario Licon Cabrera, Anuapama Pilbrow, Lachlan Brown, Debbie Lim, Michelle Cahill, Christopher Cyrill.

This stellar conference featured authors from Argentina, China, Egypt, Indonesia, the Phillipines, Myanmar, New Caledonia, and New Zealand, with keynotes by Alexis Wright and Gauri Viswanathan. Alexis Wright is an Indigenous Australian writer best known for winning the Miles Franklin Award for her 2006 novel Carpentaria and the 2018 Stella Prize for her “collective memoir” of Leigh Bruce “Tracker” Tilmouth. Gauri Viswanathan is the author of Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India (Columbia, 1989; 25th anniversary edition, 2014) and Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief (Princeton, 1998) which won several awards.

The conference also featured a launch of a documentary screening of Gangalidda political leader Clarence Walden, a witness to the cruel racism experienced by Aboriginal people during the 1950s and 60s on the remote Doomadgee Mission in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The documentary addresses the enormity of the political struggles with governments and mining companies in the modern era. Here is a link to the ABC’s audio recording of Nothing But the Truth,

(Credits: Interviewer: Alexis Wright. Sound Engineer: Russell Stapleton / Ben Denham. Producer: Ben Etherington)

The creative component of the conference is curated by acclaimed author and academic, Nicholas Jose.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

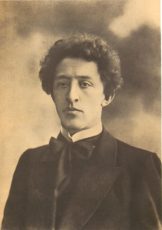

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok was born in 1880 and died in 1921. He is celebrated as the foremost of the Russian symbolists. His first book was entitled Verses about the Beautiful Lady.

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok was born in 1880 and died in 1921. He is celebrated as the foremost of the Russian symbolists. His first book was entitled Verses about the Beautiful Lady.

| Ночь,улиа, фонарь, аптека Ночь, улица, фонарь, аптека, Бессмысленный и тусклый свет. Живи ещё хоть четверть века — Всё будет так. Исхода нет. Умрёшь — начнёшь опять сначала И повторится всё, как встарь: Ночь, ледяная рябь канала, Аптека, улица, фонарь. | Night, a street-lamp and a chemist’s Night, a street-lamp and a chemist’s. This lustreless, meaningless globe. Have twenty more years, or some more. No one’s ever known an exit. You’ll die. Start it all over again: everything repeats the past. Night, an ice-cold ripple in the canal, a street-lamp and a chemist’s. |

|---|

Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, The Collection of Space. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra.

Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, The Collection of Space. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra.

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was born in 1892. She left Russia in 1922, returned in 1939, and was to die two years later. She is celebrated as one of the greatest Russian poets of the Twentieth Century. Her first book was entitled Evening Album.

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was born in 1892. She left Russia in 1922, returned in 1939, and was to die two years later. She is celebrated as one of the greatest Russian poets of the Twentieth Century. Her first book was entitled Evening Album.

| Сад За этот ад, За этот бред, Пошли мне сад На старость лет. На старость лет, На старость бед: Рабочих — лет, Горбатых — лет... На старость лет Собачьих — клад: Горячих лет — Прохладный сад... Для беглеца Мне сад пошли: Без ни-лица, Без ни-души! Сад: ни шажка! Сад: ни глазка! Сад: ни смешка! Сад: ни свистка! Без ни-ушка Мне сад пошли: Без ни-душка! Без ни-души! Скажи: довольно мýки — нá Сад — одинокий, как сама. (Но около и Сам не стань!) — Сад, одинокий, как ты Сам. Такой мне сад на старость лет... — Тот сад? А может быть — тот свет? — На старость лет моих пошли — На отпущение души. | Jardin To cope with this underworld you’ve sent me, and madness, make it a garden for the years that age. For the years that age, for the griefs I’ve to live through, the years of work coming and the groanings in my back. For the years that age. Bone for that dog. For the hell-burnt years. A garden in the breeze for their refugee. Bless me with a garden and nobody there, a soulless place. Garden no one steps in. Garden no one looks in. A laughterless garden, a no whistling there garden Earless, bless me with a garden. Nothing has a scent there, not a soul. Speak: you’ve tortured enough. A garden on its own. But don’t come near me here or there. Yes, he says, it’s as alone as me. That’s your garden for me and the years I age. That. Or your paradise? Bless me in the years that age. Deliver me from here. |

|---|

Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, ‘The Collection of Space’. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra.

Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, ‘The Collection of Space’. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Paul de Brancion is the author of about fifteen novels and poems. He is regularly involved in transversal artistic projects, with contemporary art centres or music composers (T. Pécou, J-L. Petit, G. Cagnard, N. Prost, …). He lives and works between Paris, Corsica and Nantes. Where he organises and presents “Les Rendez-vous du Bois Chevalier”, annual events dedicated to literature, science and poetry.

Paul de Brancion is the author of about fifteen novels and poems. He is regularly involved in transversal artistic projects, with contemporary art centres or music composers (T. Pécou, J-L. Petit, G. Cagnard, N. Prost, …). He lives and works between Paris, Corsica and Nantes. Where he organises and presents “Les Rendez-vous du Bois Chevalier”, annual events dedicated to literature, science and poetry.

He is editor-in-chief of the magazine Sarrazine, president of the Union des Poètes & Cie and representative in France of the WPM (World Poetry Movement).

| 36 Ça fait tout drôle, ce manque de légèreté. Des maisons, des meubles, des tapis, des mauvais livres, une sorte d’indélicatesse du goût. Comment peut-on survivre à cet environnement d’un si mauvais genre ? Profusion, c’est le mot en français. Excès. Mor avait quelque chose d’excessif que je craignais infiniment. Il était dangereux pour moi d’être en relation avec elle. Même mon amour pour elle était inconvenant. Elle parlait très vite et beaucoup. Un déluge de mots était prononcé et je m’éloignais en marchant le plus loin possible du courant continu de ses phrases. Elle était le maître de la vérité. Elle priait et sa prière était un écroulement. Elle ruisselait devant le Seigneur Dieu. Comment peut-on dire cela sans être fauteur de scandal ? Je n’arrive pas à rassembler une idée globale ou une image fixe. Toujours mouvante, elle était toujours mouvante, émouvante, éprouvante, épouvante, Mor. 43 Cette nuit cauchemar, cauchemère, j’en ai honte. Je crois qu’elle est tombée par terre dans l’entrée de damier noir et blanc froide et humide de l’enfance. Elle portait une longue robe bleu-gris sombre qui collait à son corps. Elle était allongée, elle se sentait faible. Je suis venu pour l’aider. Elle n’a pas appelé. Elle était allongée sur le sol, ses yeux étaient fermés et le teint blafard. Je sentais son cœur qui battait la chamade. C’est la fin pensai-je avec émotion. De fait, elle est morte du cœur, d’une faiblesse du cœur et non du cancer qui rongeait ses entrailles. Voilà, cela arrive enfin. Presque soulagé parce que j’ai attendu ce moment précis toute ma vie. Je les considérais, elle et le vieux panard mon père comme immortels, éternels, alors c’était cela, ils pouvaient bien mourir, eux aussi. On y était arrivé. Le grand passage de Mor. Elle est morte d’une attaque cardiaque. Elle avait pris beaucoup de médicaments. Son corps était en train de pourrir. Il a été décidé de ne pas lui inoculer des produits stabilisateurs qui empêchent qu’elle ne pourrisse de l’intérieur. Mauvaise décision Translator’s note: In Danish, 'Mor'means Mother. The original version of this poem was written in French, Danish and English. French and English were common to mother and son but Danish was his alone. | 36 It feels weird, this lack of lightness. Houses, furniture, carpets, bad books, a sort of indelicacy of taste. How can one survive in such a hopeless kind of environment? Profusion, that’s the word in French. Excess. There was something excessive about Mor that I feared greatly. It was dangerous for me to have a relationship with her. Even my love for her was unseemly. She spoke very quickly and a lot. A deluge of words was delivered and I walked as far away as possible from Mor’s continual stream of sentences. She was the master of Truth. She prayed and her prayers tumbled down. She gushed in front of the Lord God. How can one say that without stirring up a scandal? I can’t put together an overall idea or a fixed image. Always moving, she was always moving, emotional, difficult, frightening Mor. 43 That nightmare of a night, nightmother, I’m ashamed of it. I think she fell over on the cold and damp black and white checked porch of our childhood. She was wearing a sombre long blue-grey dress that clung to her body. She was stretched out, she felt weak. I came to help her. She didn’t call out. She was lying on the floor, her eyes closed and her complexion pale. I felt her heart beating wildly. This is the end, I thought emotionally. In fact, she died of a heart disease, a weakness of the heart, and not of the cancer that gnawed at her entrails. There it was, happening at last. I am almost relieved because I’ve waited all my life for this precise moment. I always considered them, her and that old dog my father, everlasting, then this was it, they too could die. It had happened. Mor’s great passing. She died of a heart attack. She took a lot of medicines. Her body was rotting away. It had been decided not to inject her with any stabilising drugs to stop the deterioration of her insides. Bad decision. |

|---|

Formerly a music educator and writer, Elaine Lewis created the Australian Bookshop in Paris in 1996. She met poet Jacques Rancourt and began translating for the Franco-anglais Poetry Festival. Her book Left Bank Waltz was published by Random House Australia in 2006. She is currently co-editor and book review editor of The French Australian Review, the journal of the Institute for the Study of French Australian Relations and is a committee member of AALITRA (Australian Association for Literary Translation). She has translated poetry from Guadeloupe, Haiti, Switzerland, Canada, La Réunion, Belgium and France, published in La Traductière and Etchings (Ilura Press).

Formerly a music educator and writer, Elaine Lewis created the Australian Bookshop in Paris in 1996. She met poet Jacques Rancourt and began translating for the Franco-anglais Poetry Festival. Her book Left Bank Waltz was published by Random House Australia in 2006. She is currently co-editor and book review editor of The French Australian Review, the journal of the Institute for the Study of French Australian Relations and is a committee member of AALITRA (Australian Association for Literary Translation). She has translated poetry from Guadeloupe, Haiti, Switzerland, Canada, La Réunion, Belgium and France, published in La Traductière and Etchings (Ilura Press).

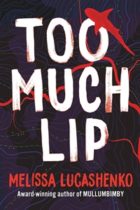

Too Much Lip

Too Much Lip

by Melissa Lucashenko

University of Queensland Press

ISBN: 978 0 7022 5996 8

Reviewed by CAITLIN WILSON

Talking Back: Too Much Lip, Melissa Lucashenko

If this book were a sound, it would be the roar of a motorcycle down an empty road; bold, and for the moments when it’s in your path, dominating of all your senses. This book swallowed me and churned me in its guts and, as all good books should, spit me back out, a little bit different.

Its premise is not unfamiliar: a woman is called to return to her home as her grandfather nears death to say goodbye, and finds more waiting for her than she had anticipated. But Lucashenko renders this framework classic rather than clichéd. Melissa Lucashenko’s name has been synonymous with vivid characters negotiating the complexities of belonging since her debut novel Steam Pigs was released in 1997. Tangled and tumultuous relationships are her hallmark, and the Salters, the family around which Too Much Lip centres, are no exception. The story boils with emotion, and its characters carry scars both physical and invisible from their shared past.

In Too Much Lip, a stranger rides into town, “but it wasn’t a stranger, it was Kerry”— the novel’s observant, funny and immediately likeable in a she-says-what-we’re-thinking way protagonist. She roars into frame on the back of Harley, headed to her hometown of Durrongo in Bundjalung country, northern New South Wales. Kerry is a marvellously difficult woman to pin down—a self-described lesbian who falls for a man, a ‘lone wolf’ who thinks often of her ex-girlfriend and cares deeply for family, almost despite herself. The novel doesn’t dwell overly on romance, but Kerry’s burgeoning relationship with her handsome former schoolmate, Steve Abarco, complicates her understanding of herself. Kerry never calls herself bisexual rather than a lesbian, a fact that was jarring at first. However, I came to see it as a part of her all-or-nothing image of the world, rather than any oversight on the part of the author. That the exception to her sexuality is a white man is even more of an about-face for Kerry, who treats the white ‘redneck’ townsfolk of Durrongo with earned suspicion:

“Had they realised at all that running was a bulwark against the taunts slung about so casually at Patto high? Nigger, nigger, pull the trigger. Kerry would sneer at the white faces mouthing the words- Abo, black bitch, boong- and picture their owners wheezing on the edge of the track as she floated past triumphant, her giant banner reading: Whatever, maggots.” ( 59)

Jim Buckley, the land-grabbing white mayor of Durrongo, slights Kerry nearly as soon as she arrives home, and threatens a beloved site of family history for the Salters. Drawn into the fight for her family’s land, Kerry is a reluctant activist, her cleverness and rage useful weapons against greedy developers. While it would be easy to call Jim Buckley the antagonist of the novel, he is only its human form: personifying white selfishness and the disrespect of Indigenous people that is all too persistent, in fiction as in historical fact. White Australia’s callous disregard for Indigenous people is the social and structural violence at work in this novel; and slaying it, or chipping away at it the best one person can, is Kerry’s heroic journey.

Too Much Lip is thus as much about repairing past damage and safeguarding against future destruction as it is about new romance. The Salters distance themselves from each other in ways literal and metaphoric. They are tough, loving, violent and soft by turns, never easy and certainly never dull. Kerry’s older brother Ken drinks and rages without quite knowing why, his son is entranced by the escapism the computer screen offers, and her mother’s Tarot cards guide her way through the world. Kerry and her middle brother, Black Superman, have put physical distance between themselves and Durrongo, and their sister Donna, missing since her sixteenth birthday, is a gaping hole of absence in the Salter family.

Despite—or perhaps because of?—its depth, Too Much Lip retains much of the dark comedy for which Lucashenko’s 2013 novel Mullumbimby was so well received. Winner of the Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, Mullumbimby also circled themes of the bittersweet familial obligation and the sacredness of land, though Too Much Lip arguably pushes Lucashenko to darker and more personal places. Lucashenko herself described the writing of Too Much Lip as “frightening” and “retraumatising”, and while the enduring rawness is evident, the novel reads as anything but fearful. Lucashenko’s characters feel real and personal. The first chapter is preceded by a quote from a 1908 court case, where an Indigenous woman has shot a man. This woman, Lucashenko reveals, was her great-grandmother, Christina Copson, and a source of inspiration for Too Much Lip’s incisive depiction of the white people in power in Durrongo.

Early in the novel, Kerry stumbles on a quintessentially-Australian image of sublime natural horror- a crow, having tried to eat a dead brown snake, has caught its head in the skeleton of the snake. This grotesquery is Australia writ-small; a penetrating force attempting to invade that which it does not understand. Three other crows that have gathered near the snake speak to Kerry in a mix of English and Bundjalung, a moment which allows Lucashenko to establish the uniquely Indigenous realism of her novel.

“The snake-crow tilted its mutant head at her.

‘Gulganelehla Bundjalung’. Speak Bundjalung. A test of good character.

‘Bundjalung ngaoi yugam baugal,’ she said. My Bundjalung is crap. The bird hesitated.” ( 9)

Moments like this evoke Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book: terming them as ‘magic realism’ undermines the deft translation of an Australian experience as real and complex as any described by a Tim Winton or Christos Tsiolkas text. Too Much Lip doesn’t gesture at universality, or attempt to speak for anyone. Instead, it speaks personally on shared issues of family, home and loss.

Indeed, one of the many remarkable feats this novel achieves is its determined peeling away of the layers of toxic masculinity to reveal the trauma at its core. The male characters in Too Much Lip, particularly the four generation of Salter men, carry heavy burdens that are revealed bit by aching bit through their interactions with each other and the women of the novel. Even the local landscape, so loved by the Salter family, imparts an omnipresent threat of violence:

“Maybe it was a dog to begin with, or a doob, for that matter. But make no mistake. That mountain’s a fist now, girl.” Pop told her, letting his arm drop. He looked at her in anguish.

“It’s a gunjibal’s fist waiting for us mob to step outta line, waiting to smash us down. We livin’ in the whiteman’s world now. You remember that.” (64)

Memories like this proliferate the novel, as the Salter siblings attempt to make sense of their past and protect their future. Lucashenko’s writing is never sentimental, and yet the careful revelation of the secret darkness rotting the heart of the Salter family is deeply moving. By lovingly sketching characters who are deeply flawed, Lucashenko hints at redemption without the need for saccharine prose. It was fascinating to read this book in the wake of the debate over the cogency of Erik Jensen’s decision to disqualify from the Horne Essay Prize “essays by non-Indigenous writers about the experiences of First Nations Australians”. While it’s a complex issue I wouldn’t presume to be able to solve, I was struck reading this book the importance of telling your own story, your own way. What makes Too Much Lip not only engaging while reading, but memorable, is its tangible roots, which burrow deeply into the realities of Australian existence, through the author, this country, and now, this reader.

Citations

Chernery, Susan. “Melissa Lucashenko: Too Much Lip was a frightening book to write”. The Sydney Morning-Herald. 27/07/18. https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/melissa-lucashenko-too-much-lip-was-a-frightening-book-to-write-20180724-h1326h.html

Lucashenko, Melissa. Too Much Lip. QUP. 2018. Pp. 9, 59, 64.

Wahlquist, Calla. “Horne essay prize scraps rule change after judges resign in protest”. The Guardian. 24/9/18. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/sep/24/horne-essay-prize-scraps-rule-change-after-judges-resign-in-protest

Wright, Alexis. The Swan Book. Giramondo Publishing, 2013.

CAITLIN WILSON is a Melbourne-based student and writer of criticism and poetry. Her poem was recently short-listed for the University of Melbourne Creative Arts poetry prize, and her criticism can be read in Farrago and The Dialog, among others.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Vishvarūpa

Vishvarūpa

by Michelle Cahill

ISBN 978-07340-4205-7

5 Islands Press, 2011

second edition UWAPublishing

ISBN: 9781760800352

Launch Speech by JUDITH BEVERIDGE

As Michelle tells us in the notes, Vishvarūpa is a Sanskrit word meaning: manifold, having all forms and colours. This aspect of diversity is beautifully played out in Michelle’s book. She ranges from different locales in and around Sydney, to Mumbai, to Dharamasala, around an impressive range of mythical and cultural references, and around voices, which are both personal and imagined.

This is a book of highly textured, rich, elegant poems that probe into Eros, power, mortality, place, dream, culture, myth. The particular way this book juxtaposes and interweaves Australian and Indian experiences makes it unique. Its contribution to contemporary poetry I’m sure will be regarded by many as highly significant, and a book that will act as an important touchstone for the way that different cultural experiences can be sustained and interwoven.

So Michelle is juggling quite a few balls with this book, yet I never had the sense that she was taking on more than she could manage, or that the risks were tipping her over, making her lose control. What is so impressive about the book is the singular strength, confidence and vigour of the language.

We as readers know when we are in the presence of language that’s being used in exciting, brilliant combinations, whose effect is immediately intoxicating. You’ll notice an astute control of diction in this book, a diction that can accommodate formal elegance, the vernacular, specialised knowledge, the mundane world. A diction that can range from words such as: tumuli, orogeny, haptic, myocardium, porcine, swithering, glutaraldehye: to crow, magnolia, butterfly, motorbikes, possum, rain.

We know as readers we have to be a little wary of poets who create dazzling surfaces, but who don’t, finally, have all that much beer under the foam. But with Michelle’s work there is a sense that text and texture are rightly married, that the poems are “imaginatively right”, that the rhythms move as the mind moves. Michelle’s poems flow exquisitely from phrase to phrase and line to line. She also has a remarkable ability to do jump-shifts that seem to change the tone quite drastically, yet still maintaining an overall coherence.

One of my favourite poems in the volume, “The Abbey” illustrates this point. This is an intensely evocative poem, full of a strange, unsettling sensuality, and it attains its power from the way in which beauty and menace play off against each other. There’s both a sense of the corporeal as well as a ghost-like insubstantiality, which provides a great deal of tension and suspense:

Why do you ask? Haven’t we already touched

as we lay on the lichen, the stones, uneven and

tessellated into a path, your hand on my dress.

We lay with forget-me-nots, whispered vows

resting our gaze. The air was heavy as the scent

of lilies stewed and spilt across the dry grass.

I felt the shock when you parted my hair.

I saw crushed petals falling from the sky

like paper moons in flawless pink and red.

I believe there was a dead dove, its neck swollen

as if it had been strangled. And I saw what looked

like one stagger into the shade of a fluted yew

We could hear the voices of those we knew,

the organ player’s notes receding from the abbey,

the sound of wooden bells. Or was it broken wings?

Impossible to read the names. How could we see

the living or the dead ghosts rise from their graves,

pacing, becoming frantic. Our eyes were stitched.

All that we saw was the soil, sweet and sad, leaves

beginning to fray, to curl, and the splatter of moss

sown like a seam through stone, a silent threnody,

a trickle beneath the earth’s skin as if something

stirred in darkness that was unspoken, the dove’s

wings, perhaps, or the heart weighing its secret.

(18)

This is a common feature in this book, the play of contradictions. Pablo Neruda in his essay “Toward an Impure Poetry” said that he wanted poems “smelling of lilies and urine”. There is something immensely appealing about juxtaposition, about the concurrence and interaction of unlike truths, of lines or sentences where one impression confronts another. In Vishvarūpa Michelle has made this her own aesthetic, she is often shifting her stance, or assertion and making us as readers feel the world as multi-toned, as manifold.

In the poem, “The Ghost Ship”, another one of my favourites, the scent of the albatross feathers are described in terms of both beauty and disgust:

a musk

pungent as magnolia, tossed with brine and bilge.

(19)

In the poem “The Chase” the speaker talks of:

the lavender scent of evening

which is a drug. It drives you to the periphery, the deepest part

of this gorge where we last crossed the river, our feet cold

amongst, the tangled roots and the rain.

(21)

In the poem “Tryptich of Wings” – the dead butterfly has one wing “bright as velvet” the other “Mendelian, a mosaic sequined with ants.”

In “Ode to Mumbai”, the speaker declares:

I hang in a gap between the sound and meaning of words

dipping my subconscious in different time zones, where

my bed is a temple and a brothel, where dream defines me.

(23)

I love the richness and all the compound, multi-layered impressions that Michelle evokes. She seems so able to make cosmos out of chaos. Her two poems about Mumbai – “Ode to Mumbai” and “City of Another Home” so adeptly portray the multitudinous and multifarious aspects of such a place. All the contrapuntal comings, goings and doings of a wide-range of people- from the haggling women, the taxis, the beggars, the spivs, the sadhus, the cows, the dogs, the middle class folk, the members of a Laughter Club, the auto-rickshaw drivers that inhabit Mumbai are all so seamlessly threaded through the poem, and by the end we get a sense of rightness and peace:

City of divine deliriums, the dogs are chained. the Laughter Club

members fatigue their raucous morning bellows from a plinth

of recreational park. the auto-rickshaw wallahs doze in the shade.

(39)

Some of the most powerful poems in the volume are the poems, which either speak about or assume the voices of various Hindu Gods and Goddesses. There’s ” Kālī from Abroad” ” Pārvatī in Darlinghurst, ” Durgā: a Self Portrait”, “Ganeśa Resurrected “”Laksmī Under Oath” to name some of them. Michelle has a great deal of fun with these destructive and capricious deities. She modernises them, flirts with them, taunts them, brings their faults and foibles to the fore. There’s a strong sense of the erotic, of taking these figures off their pedestals and revealing their feet of clay. These are multi-toned gods and goddesses revivified in contemporary settings.

Kālī is described as ” adroit in drugs and aphrodisiacs/ a nude dominatrix/ a feminist export with a sado-masochistic bent”. She wears “punk-blue leggings” and has “skull-and-scissor charms.”

Here’s the goddess Pārvatī speaking of the affair between herself and Shiva in the poem “Pārvatī in Darlinghurst”: The tone is sarcastic. Pārvatī is confident, fully empowered, full of her own intentionality and will:

We scorned the Purānas, our tryst no Himalayan

cave, but a hotel bed I had draped with stockings,

lingerie, and the crystal ice of a Third Eye. I admit

that’s why I spoke with the speed of an antelope.

It seems the acharyas were mistaken: I hadn’t

dated for marriage or adultery, nor with a wish

to deck his house with flowers or sweep his floors.

I am too busy, I declared, for dalliance or abstract

gossip. I have no interest in honeybees and birds.

All I wanted was a good time. I swear as the river

is my sister, that this guy was not my sun or my sky.

No way did it even enter my mind to have his kids.

His first wife’s ashes are scattered all over the city.

Goddamn it, Shiva is a walking disaster; whatever

he touches burns.

(57)

Again the language is uncompromising, beautifully weighted and nuanced.

I found that Vishvarūpa kept me engaged with its rhythms and patterns of sound, with its narrative power and sense of exact detail, with the way the imagery and tone negotiate the very subtle changes of mood or modes of feeling. I love the humour, the nostalgia, the regret, the obstinacy, the tenderness.

There is so much more I could say about Vishvarūpa, there are so many fine poems I haven’t touched on or mentioned. So I urge you to buy it and relish in the poems as I have. I’d like to end on a quote by Octavio Paz because I think it sums up that wonderful quality that Michelle’s poetry has:

Each time we are served by words, we mutilate them. But the poet is not served by words. He is their servant. In serving them, he returns them to the plenitude of their nature, makes them recover their being. Thanks to poetry, language reconquers its original state. First, its plastic and sonorous values, next the affective values; and finally the expressive ones.

Michelle has done all of this is in her book and I’d like to congratulate her and 5 Islands Press for the great gift of Vishvarūpa.

JUDITH BEVERIDGE is the author of six collections of poetry, all of which have won major Australian book prizes or been shortlisted. Devadatta’s Poems (Giramondo Publishing) was short-listed for the NSW and Qld Premiers’ poetry prizes and the Prime Minister’s Poetry Award. Hook and Eye, ed Paul Kane was published by Braziller in New York. Sun Music: New and Selected Poems, was published in 2018 by Giramondo.

out of emptied cups

out of emptied cups

by Anne Casey

ISBN: 978-1-912561-74-2

Launched by ELEANOR HOOKER

The Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote poetry is a ‘dividend from what you know and what you are’.

I am going to tell you about Anne Casey, the person, things I imagine you already know – Anne is a powerhouse, a force for good in a world where cynicism and doubt abound. She is collegiate, kind and considerate of her fellow poets, wherever they might live – just look at her social media, her reach and her conversations are global, she celebrates our successes and commiserates when we miss – that’s a rare thing and something to be cherished. Thankfully, Anne’s accomplishments and achievements have not changed her, she is too steady and noble a character to have her head turned by that.

The poems in out of emptied cups, Anne’s second collection with Salmon Poetry, make the unseen appear, whether it is beloved family members long gone, souls transitioning between this world and their next incarnation, or monsters (who are ever denied a hiding place in a Casey poem).

In many of Anne’s poems, tragedy and joy collide, and it is this collision that moves her poems toward: action – that which nudges us toward conscience, ecological consciousness, and self awareness, and, discovery – that which incites in us the wish to live well. I will talk about this later.

Just as a cinematographer uses a camera, Anne uses language in her poems to create a visual aesthetic – in her poem ‘out of a thousand cups’ (the first poem in the collection) Anne employs a filmic pan to show us the ascent of a soul before its turnaround and return to re-emerge in a different form, and the effect is feather light.

She uses the same technique in ‘All Souls’, the final poem in the collection – shifting between the noises, sights and sounds of Australia, and those desperately poignant images of her mother, delivered of a terminal diagnosis and yearning for her child, twinned with a suffocating religious iconography, associated with old Ireland. All of this is in contrast to the openness and natural exuberance of her adopted homeland, where ‘rainbow lorikeets… ‘will swoop… lifting our hearts/out of emptied cups and away with them into/the heavens’ – a suggestion that Australia is the land where Anne will live out her days.

When I’m editing footage from a lifeboat rescue, I’m careful where to place transitions so as to move the story of the callout scene from scene – transitions are like a blinking eye, that, each time it opens it encounters another image, another time. Anne places her ‘transitions’ to masterful effect in her poem ‘if I were to tell you’, as she shifts our view place from place and person to person central to her life – the second verse is a heart-stopper and illustrates how in describing the personal, that moment of wanting to speak to a parent and remembering that they have died, Anne depicts a universal moment of grief. (I was brought back to a moment soon after my own Dad died when, alone in my car on my drive home, I called out ‘Dad?’ – I frightened myself, and the absence of a response was just desperate.)

This collection includes poems that are at once mysterious and captivating. ‘Wildness’ is a personal favourite, and though the wild creature is never named (and that restraint adds power to the poem,) Anne draws on the many tropes of woman as shape-shifter: selkie; of the woman-hare that links to the Otherworld (a notion central to Irish folklore – Aos Sí), and even to the concept of doppelgänger. At another level the poem is about woman denying her true nature, suppressing her instincts. Interestingly, at her launch, Anne gave an altogether different account of this poem – which shows how a reader imports meaning to a work.

and I will curl up

wrap myself in your shed skin

and marvel at its length

its strength

its tenderness

all that had held you back

your wildness denied

This haunting poem encapsulates one of the central themes in out of emptied cups, that of a woman navigating an often unforgiving world, but ultimately recovering self and strength through family and history, by loving and being loved.

If poetry is the closest art we have to silence, Anne’s poems frame the silences. She is fearless in observing what can and should be named, and what should remain unnamed.

Jane Hirshfield has said that one of the ‘laws of poetry seems to be that there can be no good poem of unalloyed happiness, that good poems always pull in two directions’, and this is certainly what Anne achieves in her book, that sudden shift, that collision, achieved purely by precision of words.

A wonderful example of this (and of an exquisite employment of visual metaphor and experimentation with form), is offered in Anne’s poem thank you for shopping with us – a remonstration that our eco-destruction will literally cost us our earth.

This collection is one of vitality and rhythm. It uses the music of words to make silence felt, and leaves the reader with the glad appreciation that there is so much more to poetry than meaning alone.

Before I conclude I would like to acknowledge the Trojan work Jessie Lendennie and Siobhan Hutson do at Salmon Poetry, their support for poets and especially women poets is phenomenal and is celebrated; the Press is an inspiration.

I will finish with another quote by Czeslaw Milosz written in 1996 and as pertinent today as it was then, and which relates both to Anne’s poetry and Salmon Poetry – ‘that poets today can form a confraternitas transcending distances and language differences may be one of the few encouraging signs in the current chaotic world order.’

Congratulations Anne, I wish you and your work every success.

Photograph: Anne Casey with Eleanor Hooker and Luka Bloom

ELEANOR HOOKER is an Irish poet and writer. She has published two poetry collections with Dedalus Press: A Tug of Blue (2016); The Shadow Owner’s Companion (2012). Her third collection will be published in 2020, she is working on a novel. Eleanor holds an MPhil (Distinction) in Creative Writing from Trinity College, Dublin, an MA (Hons) in Cultural History from the University of Northumbria, and a BA (Hons 1st) from the Open University, UK. Eleanor is a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London (FLS). She is a helm for Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.