Jack Stanton reviews The Grass Library by David Brooks

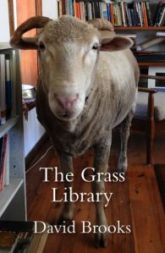

The Grass Library

The Grass Library

by David Brooks

ISBN 978-0-6482026-4-6

Reviewed by JACK STANTON

“If only ethics operated on the one plane,” (137), David Brooks laments in The Grass Library, which, like his previous work, evades neat classification but falls somewhere in between memoir and philosophy. On one level, The Grass Library urges his readers to reconsider their relationship with our fellow earthlings, through his own disenchantment with eating animals. To summarise the narrative, however, would be reductive. On the macro level, the story begins when Brooks and his wife T. Become vegan, beginning a chain of events that results in them exchanging their life in Sydney for a farm in the Blue Mountains. This is precisely what makes the book interesting: he knows how to locate and illuminate the ideologies that underpin daily life, in a way that blooms naturally from his own experiences.

From what I take away, Brooks’s central argument is that our dominion over animals is mostly a product of a particular state of mind, an entitlement, which “has difficulty navigating the rough terrain of reality” (213), a difficulty enforced by ancient social/cultural/historical “fences” established between animals and humans. For Brooks, these fences are ideological, fixed in the ways we talk about animals.

Indeed, writing about animal rights and vegan/vegetarian activism has a long literary tradition behind it, one that Brooks self-consciously writes within. He is in good company, the likes of Tolstoy, Kafka, Mary Shelley, and Plutarch. Tolstoy was famed for denouncing eating animals as profligate and senseless. “A man can live and be healthy without killing animals for food,” he writes, “therefore, if he eats meat, he participates in taking animal life merely for the sake of his appetite.” What Tolstoy saw as moral responsibility actually reversed the hierarchy of power, with humans, at the pyramidion, seeking to protect rather than exploit those beneath them.

Brooks writes about his metamorphosis from an omnivorous Sydneysider to owner of his refuge farm in the Blue Mountains, a fresh vegan seeing the world anew, all the while trying to find a harmony with animals, forever writing down his observations of how humans should (or were meant to) live. I use this word, metamorphosis, rather than a less-decorative cousin, such as ‘change’, because there’s something essentially creatural in Brooks’s becoming. He transgresses “fences”, (51) a metaphor for boundaries within the human mind and language. “You don’t realise the guilt you’ve been carrying around until you no longer feel it,” he writes. (10)

On the surface, The Grass Library tells a simple story. In the Blue Mountains, he begins to establish a sanctuary for wayward animals, most notably their dog Charlie and four sheep: Henry, Charlie, Orpheus, and Pumpkin. But in true essayist style, Brooks tells the reader they’re in for more than what’s on the narrative surface—“this book isn’t about veganism, or guilt,” he writes, “but ultimately and more simply it’s about discovery and wonder: wonder, and wondering.” (10)

Which is true: Brooks doesn’t moralise. He focuses on identifying problems about writing about animals in the first place, because already I’d started to encounter these [problems], the way the language seems stacked against them, conditioning us, subliminally, to keep up the cruelty. (17)

Here, I agree with Brooks. Consider the French: fruit de la mer. Fruit of the sea. This is what Brooks means by a “fence” in language.

But before getting too far ahead, a brief aside á la subliminal conditioning. When Brooks suggests “if something seems untenable then perhaps is it because it suits the status quo to have it seem so” (17), he is urging readers to challenge their hardwired, default setting. In his speech ‘This is Water’, U.S. writer David Foster Wallace argued that our default setting is the belief that we are the absolute centre of our own universes. He further argued that being able to recognise your default setting and push against it was the “no bullshit” real life value of a liberal arts education.

But are these just semantics? Or do the words we use to talk about animals have real life meaning in our treatment of them? Predictably, Brooks argues in favour of the importance of language and its relationship to reality, quoting Friedrich Nietzsche’s phrase “we see all things through the human head and cannot remove that head.” (25) Here’s an example. While discussing his first two adopted sheep, Henry and James, Brooks writes against traditional wisdom, which advises don’t give them names . .. because then you won’t be able to use them, by which is meant kill them, or to do so readily the other things you need to do to them. (52)

This juncture in language is best seen through binaries, such as pet/livestock, common/endangered, wild/tame, and so forth. These distinctions “masquerade as recognition of some value inherent in the animal itself.” (74) In other words, the use (or misuse) of language positions animals as property, closer aligned to a ‘thing’ than a person, and, Brooks opines, people don’t often name their property; it’s considered strange to befriend your fridge.

In Katoomba, Brooks witnesses two tragedies. During the first, he sees ducklings swimming in his pool. Some have drowned. Their mother swims beside them, idle, either confused or unsure about what’s happened. He scolds himself. The ducklings have drowned because the pool’s water level has declined. The tired ducklings couldn’t escape.

The second tragedy is even more minuscule. A cicada trapped inside its own shell, midway through its metamorphosis. It’s here, using the microscopic world as a gateway to the philosophical one, that Brooks’s The Grass Library is at its most compelling. He creates this gateway by pondering the above two tragedies, thus:

If the word tragedy can’t accommodate a drowned duckling or a cicada trapped in its own larval shell then we must ask not only how much of its use to us is a tool for defence of our own self-centeredness and misguided mastery, but also how many other of our implicit, unquestioned, and seemingly innocent assumptions might be the same. (129)

Like any considered perspective, Brooks pre-empts and refutes the stances contrary to his own. He isn’t bothered by accusations of anthropomorphising, responding with an accusation of his own, namely that “barbarity itself begins with the thought that we are so different from the creatures we live amongst that we cannot know or even hazard how they feel.” (25) Yet another fence in the mind.

Besides, what Brooks has set out to achieve in The Grass Library pretty much depends on being able to speculate on, and empathise with, the animals he lives alongside. He describes the book as a narrative turned “upside-down” (68), not about his life with T. in the mountains, or only ostensibly so. Instead he has devised a narrative in which “the animals that are normally suppressed or swallowed by a story, or serve as accessory to it, have been brought toward the ‘fore’, and humans play a more supporting role.” (68)

And true to the upside-down nature of this meditation on animals in philosophy is a scene from the opening pages that has stayed with me, a scene in which Brooks sees a spectre from his past, a version of himself wandering along Martin Place, while he was protesting the use of battery cages. Brooks, a senior lecturer at USYD, is crammed into a cage in Martin Place, wearing a chicken mask—watching the vice-chancellor of my university walk by, brushing aside some of my fellow protestors in the same cavalier way I might have used myself a year or so before. (11)

Yes, the anecdote is attractive for its amusing imagery. But it also conveys a powerful second image behind the immediately comic idea of Brooks wearing a chicken mask, because here we see the strength of Brooks’s metamorphosis of the mind. Throughout The Grass Library he has tried to see the world through their eyes, wearing an animal mask while he writes.

JACK CAMERON STANTON is a writer and critic based in Sydney. His work has appeared in The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney Review of Books, Southerly, Mascara Literary Review, Overland, and others. He teaches at UTS.