Gareth Morgan reviews Ashbery Mode Ed by Michael Farrell

Subscriber Only Access

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Accessibility Tools

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

On Scars and Flying Horses:

Linda Christanty is an Indonesian author and journalist. Her writing has been recognized by various awards including the national literary award in Indonesia (Khatulistiwa Literary Award 2004 and 2010), award from the Language Center of the Ministry of National Education (2010 and 2013), and The Best Short Stories version by Kompas daily (1989). Her essay “Militarism and Violence in East Timor” won a Human Rights Award for Best Essay in 1998. She has also written script for plays on conflict, disaster and peace transformation in Aceh. It was performed in the World P.E.N Forum (P.E.N Japan and P.E.N International Forum) in Tokyo, Japan (2008). She received the Southeast Asian writers award, S.E.A Write Award, in 2013.

Linda Christanty is an Indonesian author and journalist. Her writing has been recognized by various awards including the national literary award in Indonesia (Khatulistiwa Literary Award 2004 and 2010), award from the Language Center of the Ministry of National Education (2010 and 2013), and The Best Short Stories version by Kompas daily (1989). Her essay “Militarism and Violence in East Timor” won a Human Rights Award for Best Essay in 1998. She has also written script for plays on conflict, disaster and peace transformation in Aceh. It was performed in the World P.E.N Forum (P.E.N Japan and P.E.N International Forum) in Tokyo, Japan (2008). She received the Southeast Asian writers award, S.E.A Write Award, in 2013.

Linda Christanty begins her short story “The Flying House of Maria Pinto” with a seemingly mundane encounter: an Indonesian soldier gets on a train, sits down next to a young woman reading a Stephen King novel, and tells her a story. The story he recounts is that of Maria Pinto:

“Maria Pinto was originally just an ordinary young girl who had once studied literature at a renowned university in Jakarta, and held out until the third semester before returning to the land of oranges and coffee. The people in that land died too early; they disappeared, committed suicide, went mad or plunged into the forest to unite the wild boar and the reindeer.”

Maria Pinto’s people give her ancient weapons and a flying horse, choosing her as their protector and commander.

“As of that moment, Maria Pinto had become the leader of treacherous troops, trapping the enemy in every zone, deterring those who only relied on tangible things; those who shunted aside fairytales and dreams.”

We as readers will not be able to set aside so easily the fairytale aspects of this short story; the soldier’s dreamlike narrative comes to overtake the rest of the plot. The woman on the train tries to ignore the overly chatty soldier, returning to her book until finally arriving at her destination. But after parting, the soldier is tasked with killing the enemy rebel target. He shoots at a figure on the street from a neighboring skyscraper and, when he goes to recover the body, discovers that this rebel is actually woman on the train who had listened to his story. Is the woman from the train the same enemy rebel from the soldier’s tale, Maria Pinto? That question remains unanswered, but what becomes clear is how political conflict finds its articulation in close, personal encounters and everyday stories.

Christanty is an Indonesian author known for approaching social and political issues in her writing. A student activist who participated in the movement that forced Indonesian dictator Suharto from power in 1998, Christanty has long dedicated her life to activism as well as the written word. After Indonesia’s return to democracy, she worked as a journalist and human rights advocate for women’s issues. For her activism, she was nominated for the N-Peace Award in 2012 in the Asia Pacific category and won the Kartini Award in 2014. Meanwhile, her fiction has won a range of national awards as well as Thailand’s prestigious Southeast Asian Writers Award in 2013.

According to the introduction to her collection, Final Party and Other Stories, in which the short story “The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto” was published in Debra Yatim’s English translation, “[Christanty’s] political activism is reflected in her prose . . . It is as if she feels the need to tell these things in order for us not to forget, and also maybe not to flinch when facing the demons of history.”

“The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto” is no exception. Though more implicit than her other stories in its political content, this narrative encodes questions of military violence and resistance. In fact, it is the inclusion of a second narrative plane–the mythical tale integrated into the direct encounter between the representative of the state (the soldier) and the representative of resistance (the woman)–that comes to command our attention and the progression of events itself. Indeed, the soldier’s story could be understood as a meta-narrative that reveals how this figure understands his own pursuit of this so-called “enemy.” The fascinating quality of “The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto,” and of Linda Christanty’s fiction more generally, lies not in literal depictions of conflict, but rather in the socially constructed narratives of conflict she interrogates through multiple layers of storytelling.

I spoke with Linda Christanty in Jakarta in 2019 as part of a series of interviews with contemporary Indonesian writers who represent Suharto’s New Order dictatorship in their work. The project is an effort to understand how authors construct counter-histories about an authoritarian past that the Indonesian state refuses to recognize for its brutality. As a U.S. American, I recognize the role my country played in supporting the anti-communist Suharto regime and turning a blind eye to the gross violations of human rights that took place. This traumatic past is not bounded by Indonesia’s nation-state boundaries; it is a history that incorporates global actors and that remains relevant beyond Indonesia. For foreigners, exploring how Indonesian writers revise and reconstruct narratives of the past can be a way to revisit questions of post-colonial, transnational leftism, which found its initial articulation through the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung before the Suharto era ruptured bourgeoning international solidarity between recently independent nations.

Christanty is well positioned to reflect on politically committed writing in Indonesia, both in terms of her role in her generation and independently, as an author. As a key figure in a literary movement that used words first for liberation against an authoritarian regime and then for the project of reckoning with that authoritarian past, Christanty has witnessed marked shifts in Indonesia’s literary scene. And, in her own short fiction, the question of how characters invent narratives to understand their own experiences of social upheaval remains central, whether in “The Wild-cherry Tree,” where we find ourselves immersed in the imaginative perspective of a young girl processing assault, or in “The Final Party,” where an informant who sent friends to prison copes with his choices while arranging his birthday party.

When Linda joined me in a bustling café in central Jakarta, we spoke about free expression under dictatorship, continuities in violence, literary categories, and the Western gaze on socially committed Southeast Asian fiction. Much in the line of “The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto,” the question that spanned each topic was narrative itself, and how the language we use to tell stories frames history.

*

Lara Norgaard (LN): The memory of Suharto’s New Order dictatorship is a near-constant feature of your short fiction. Almost all of your short stories in the English-language collection Final Party and Other Stories relate in some way to that period’s violence, though sometimes that connection is not immediately apparent. Some of the moments that I found especially interesting are ones in which this history is implied in language rather than made explicit. For example, in “The Final Party,” when a man who had worked as a state informant recounts how he explained his job to his daughter for her school project:

“One day, little Alma asked about his work.

‘What do you actually do, Papa?’

‘I’m a note-maker.’

‘Note-maker?’ Little Alma laughed.

‘Yes,’ he answered firmly.

But in his daughter’s report book, he wrote down: entrepreneur.”

On a level of language, how would you say Indonesian either contains the memory of Suharto-era state violence or actually obscures the history of that period?

Linda Christanty (LC): There are a few expressions that people would use in the Suharto era, and especially language used by Suharto’s government. For example, most people, including any member of the military or the police, would very rarely say, “that person was arrested” or “that person was taken to prison.” Instead, they would usually use the phrase, orang itu diamankan – “that person was secured.” As all of us who were alive in that era, secured means that someone was arrested. It immediately had that connotation, conjuring up an image of someone who confronted the state apparatus and had to be “secured.”

It was also unusual, or taboo, to use the word buruh in the Suharto era. Worker, working class, labor. The government preferred that people use the word – employee – so that power relations would disappear. As a result, there wouldn’t be any apparent power dynamic between higher-ups and subordinates, bosses and workers, or in fact any oppressive relationship at all. That’s because the term karyawan in Indonesian relates to the term berkarya, someone who creates, someone who says something in the world. Buruh, on the other hand, means laborer, someone who only has the power to work. That person does not have authority over anything else; for example, they do not control the means of production. In that sense, when we use the word labor, it means resistance, because it means that oppression is present. When Suharto was in power, if a person used the word buruh it meant that they were also radical. Buruh is a word that collects or contains radical social movements and a long history of struggle. That was erased. So you would use more neutral terms: karyawan, which means employee, and kerja, which means work or job.

Then there’s one more example from when I was little. One day, I was talking to my grandfather in our house on Bangka Island. A man passed by out front, the father of a friend of mine from elementary school. My grandfather told me that this person, my friend’s father, wouldn’t ever be able work again at his company because he was terlibat – involved. In the Indonesian of Suharto’s New Order, the word terlibat always connoted being involved with the Indonesian Communist Party. ‘That person was involved,’ and people immediately or automatically knew that they had connections to communism.

There were so many euphemisms back then, you would hear the word terlibat and diamankan, and then the word buruh was erased, it never appeared.

LN: After the Reformasi period in 1998, when Suharto was removed from power and Indonesia returned to democracy, did these euphemisms continue?

LC: When Reformasi took place, or even before Reformasi when social movements were growing stronger and labor strikes and student actions were more and more frequent, people did start using the term labor, buruh, again. For example, when they would talk about labor or factory movements. And progressive students, the ones concerned about labor, would also use the term. Indeed the intellectuals at the time became a kind of driving force for change, recuperating this language that had been banned.

LN: For you, specifically, how has this influenced your writing?

LC: I started writing fiction when the New Order regime was still in power. Back then, if you wanted to write something or send a short story to print media, like a newspaper, the government had established rules. You couldn’t break the rules, so your story couldn’t contain any elements related to politics, religion, race, or anything that was seen as going against Indonesian society. The point is, you couldn’t have critical thought in your stories. But you could package it with something other than what you meant.

In fact, in the early 1990s I was writing fiction and news stories about the lives of marginalized peoples. And I also wrote stories about factory life. Usually, I wouldn’t write those for mainstream media, but instead for student magazines. At the University of Indonesia, which was my university, and also at other schools in Solo or Yogya, a subset of the student body was involved in the student movement. And some students who were quite forward-thinking, brave, and critical would publish work more freely, allowing people to write relatively unfettered by censorship, at least in comparison to mainstream media.

LN: In an interview with the online publication Arsip Publik, you stated that you don’t like the term “Reformasi literature.”1 I see your argument that this label makes it seem as though no one was openly writing critical texts before the transition to democracy took place. At the same time, I imagine that the experience of writing was indeed different before, during, and after the transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

If you don’t like the term “Reformasi literature,” how would you reframe shifts in the Indonesian literary world since the early 1990s?

LC: There are differences, of course, especially in what I was telling you about how certain words changed in their use. I still remember how, before Reformasi, right around 1997, we would usually use the term wanita (lady) when talking about perempuan (woman). The word for lady was seen as carrying more respect than the word for woman, as though the term perempuan had a certain negative connotation. But then, the Indonesian women’s movement was active at that time, and I still remember how in one issue of the magazine Kalyanamitra, they began to use the word perempuan to bring awareness to readers, to define the concept of perempuan and how it could in fact be emancipatory. The word perempuan, or woman, has something that could be understood as equality, a kind of strength. And so they began to use that term.

Writing under Suharto’s New Order is like what I already described. If you wrote for mainstream media, you would worry that they wouldn’t publish certain things. That wasn’t just about specific terms but also about certain topics. For example, it would of course be difficult to write realistic stories about Timor-Leste or disappearances. So writers like Seno Gumira Ajidarma, when he wrote about Timor-Leste, had to make the incident occur somewhere else, and make the characters from somewhere else so readers could maybe imagine this had happened in Latin America, for example.

I felt some of that myself, but I usually sent my stories to student publications because I wrote critically and said what I thought without allowing sensors to limit my work.

For literature after Reformasi, what’s actually very interesting is how varied the subject matter became. So many authors chose to write openly about their bodies after Reformasi. In the period before Reformasi, women were not free to write about their bodies. There are some personal aspects to that, but it also relates to how women’s bodies were associated with the leftist women’s organization Gerwani. During the Lubang Buaya incident2, these women allegedly danced naked and cut off the generals’ genitals. So, women’s bodies under the New Order regime were always associated with something evil, something immoral, something violent. And as a result, women could not easily speak openly about sex or sexuality.

But men could write exotic stories under New Order regime. No woman writer could so easily discuss the sorts of things that men wrote when they described women’s bodies or sex so openly. While men wouldn’t get any social pushback, women felt like it might be incriminating if they wrote about the same things. So, later, Reformasi was also marked by the appearance of novels that were more explicit because women were free to talk about their bodies, to write about eroticism and other aspects of their own experiences.

Of course, it was also during Reformasi that stories from the Suharto era—stories that people had been too afraid to talk about– started to be told. That includes political issues, injustices, and human rights violations that people hadn’t been brave enough to discuss.

LN: How about in the present?

LC: Actually, these problems from the New Order continue today. That includes, for example, human rights violations and gendered violence, which have continued since the New Order. Over the course of 50 years, not much has changed. Take women’s issues. Rates of sexual assault are still very high, violence is still very common. In 2019, the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) published a report3 stating that violence against women increased by 14% from 2018. It’s unclear if that’s actually because there are more victims or because survivors are more and more likely to come forward, but regardless, the rates are high and the numbers haven’t dropped. Now, in terms of human rights violations or the criminalization of environmental activism, those are things that happened during the New Order and that still happen today.

Today, when people defend their land, or defend land that companies want to seize from communities, or when they defend the environment and try to prevent heavy metals from destroying rivers and fish, that’s considered a political act. That’s taking a stand, not just against companies, but also against a sector of the elite within our government. During the Suharto era, a political act was understood only as speaking out against the state and the military. Now, activists who don’t want companies on their land are also taking a stance against the state. Environmental issues are very crucial, on the same level as other human rights issues.

I see myself, along with Leila Chudori and Ayu Utami, as writers who grew up under the New Order and who were already in our twenties when Reformasi began. So we were born into that regime and lived under it through our early adult lives. That means our way of thinking, our memory, is very tied to that period. We are motivated to write about things like the 1965 Tragedy4 because that period, or stories about that period, are so strong in our memories. We write about what took place a bit later on, too, like activism under Suharto. That’s a common narrative in our lived experience. When we write about these topics, we’re also writing as witnesses, or maybe as people who grew up hearing these stories, as people who knew about or who may have been affected by the disappearances.

After us, there is a group that is far more distant from these stories. For some, their writing does touch on themes from our generation. But a different group has already moved on to write about other topics, which are not any less interesting but that also don’t necessarily depict authoritarian regimes or imagined dystopias.

For instance, Ziggy Zezsyazeoviennazabrizkie is one writer from the current generation that’s very interesting, in my opinion. She writes about a completely different world, and politics come through in her selection of symbols. Her novel, Semua Ikan di Langit (All Fish in the Sky) really impressed me. It takes place in a huge trash heap. Her main character is the corpse of a little boy. Her other characters are a cockroach and some fish, and they all ride together in a broken city bus that had been dumped in the trash heap. It turns out that the corpse becomes a certain kind of god or idol for these strange creatures. So the bus is flying along in this universe of trash, and one day it stops and a little girl gets on. The girl, who is actually the boy’s sister, is a Holocaust survivor. In this sense, Zezsyazeoviennazabrizkie writes about an event from the past, but her approach is very different from the one that my generation takes when we talk about similar topics.

LN: I’d like to hear more about your own approach. You’re a journalist as well as an author of fiction, and a lot of your stories have direct connections to real political issues. Your writing is far less surreal than Zezsyazeoviennazabrizkie’s, for example. When you write fiction, are your stories grounded in the kinds of events you yourself witnessed or in reportage about specific events?

LC: Well, let’s look at one of my stories, “Fourth Grave”. It’s about a young girl who is disappeared. Actually, I never say that she is based on someone real because she and her family are not real at all. In the story, there is an old married couple of Chinese descent, and their daughter is involved in politics. Up to this point, it’s all fiction. But were the disappearances real? Yes, they were. So I imagined a situation in which the daughter is kidnapped, like what happened to so many people who really were disappeared.

The story is about what I don’t know, like how a family would react if their child is disappeared. How does that affect the relationship between husband and wife? How do they remember their daughter? What is most painful in day-to-day life? It turns out what hurts are the little things, like when the wife wants to cook fish, but then all of sudden the husband says, don’t, our daughter might have been thrown in the sea. Memories arise, and they imagine what it might be like if their daughter had ended up in the ocean and then was eaten by a shark. And then they saw the fish in a totally different light, and they can’t eat it again.

LN: There are readers who say your stories are very sad.

LC: That’s true.

LN: I agree that they’re dark, but at the same time you include some whimsical elements. “Fourth Grave” actually has a lot of fantastical references to comics like Kho Ping Hoo, and “The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto” involves a supernatural flying horse, for instance. Could you comment on these dimensions of your work that are less realistic? What role does whimsy and fantasy play in political storytelling for you?

LC: Perhaps these elements, which many people would label magical or fantastical, are actually very everyday aspects of Southeast Asian societies. People believe that in addition to what we see in this dimension, there are also creatures alive in a different dimension. In belief systems or cultures around Southeast Asia, these elements are understood as ghosts or creatures on the threshold.

For example, where I was born on Bangka Island, people believe in 20 different kinds of ghosts. There’s a ghost that appears just as a head, for instance, called Anton, like the name for a little boy. Another one is called Hantu Burung Kuak, or Kuak Ghost Bird. If that one releases a specific kind of noise, it means something bad will happen. The ghost Menjadin can tear people apart. Aside from those, there are ghosts from Java that are pretty well known, like Kuntilanak, which is also called Pontianak in areas near Kalimantan. That means that in Malaysia, it’s also not uncommon to also hear about a ghost called Pontianak. Then there’s a snake ghost named Paul, like a white man. And there’s one called Mawang, too.

People who live on Bangka Island, in Sumatra, and even in the eastern islands of Indonesia, like Maluku or the Nusantara region, they take it for granted that these creatures are a part of their everyday lives. So when someone writes a story set in a society like ours, non-human characters are just normal. They aren’t strange. They just describe what’s going on in that other dimension.

When I wrote “The Flying Horse of Maria Pinto”, for instance, it was inspired by a trip I took by train. It was just one very brief moment. While I was in the train, I met a soldier. And during the New Order I really didn’t like soldiers, you know. I thought, oh no, a soldier is sitting next to me, how should I act? This was maybe five years before the New Order ended. Since I didn’t want to talk to him, I started reading some novel, I don’t remember which one.

That soldier wouldn’t stop talking to me, and then I noticed that he had a scar. From there, I started to imagine what I would end up writing in the short story.

NOTES

1. Sastra Reformasi, or Reformasi literature, is a term used in Indonesian literature to refer to an outpouring of openly critical literary production in the wake of the country’s transition from authoritarianism to democracy in 1998. Linda Christanty’s argument as to how this literary category obscures the tradition of critical writing before Suharto’s fall from power can be found in her interview with Arsip Publik: http://arsippublik.blogspot.com/2015/01/wawancara-linda-christanty-2.html.

2. Lubang Buaya is an area on the outskirts of Jakarta where seven Indonesian generals were murdered in 1965 in an incident that came to be known as the 30 of September Movement. The incident became the justification for Suharto’s military coup d’état and the ensuing mass killings, imprisonment, and persecution of members of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and affiliate organizations (including the Indonesian Women’s Movement (Gerwani) and the Institute for the People’s Culture (Lekra)), as well as people with any perceived connection to the aforementioned groups. For more information on Lubang Buaya and its role in the foundational myth of Suharto’s authoritarian regime, see John Roosa’s Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’État in Indonesia (https://uwpress.wisc.edu/books/3938.htm).

3. The full annual report can be accessed online here: https://www.komnasperempuan.go.id/read-news-siaran-pers-catatan-tahunan-catahu-komnas-perempuan-2019%20.

4.The 1965 Tragedy refers to the mass killings of 1965-1966 that took place in the wake of Suharto’s coup d’état. Estimates on the number killed range from 500,000 to three million people, and researchers have made the argument that the killings should be considered genocide. For more, see The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres by Geoffrey Robinson

and The Army and the Indonesian Genocide: Mechanics of Mass Murder by Jess Melvin (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/15/killing-season-geoffrey-robinson-army-indonesian-genocide-jess-melvinreviews).

This interview, translated from the Indonesian by Lara Norgaard, was edited and condensed for clarity.

Lara Norgaard is an editor, essayist, and literary translator from Colorado. After graduating from Princeton University in 2017, she served as Editor-at-Large for Brazil for Asymptote Journal and directed Artememoria, a free-access arts magazine focused on the memory of Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship. Her essays, literary criticism, and translations can be found in publications such as the Mekong Review, the Jakarta Post, Asymtptoe Journal, Peixe-elétrico, and Agência Pública. Currently, she is a Henry Luce Foundation Scholar at the Lontar Foundation in Jakarta, Indonesia and will begin her Ph.D. in comparative literature at Harvard University in September 2020.

Lara Norgaard is an editor, essayist, and literary translator from Colorado. After graduating from Princeton University in 2017, she served as Editor-at-Large for Brazil for Asymptote Journal and directed Artememoria, a free-access arts magazine focused on the memory of Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship. Her essays, literary criticism, and translations can be found in publications such as the Mekong Review, the Jakarta Post, Asymtptoe Journal, Peixe-elétrico, and Agência Pública. Currently, she is a Henry Luce Foundation Scholar at the Lontar Foundation in Jakarta, Indonesia and will begin her Ph.D. in comparative literature at Harvard University in September 2020.

Scott-Patrick Mitchell (SPM) is a non-binary West Australian poet, writer and spoken word artist. SPM’s work appears in Contemporary Australian Poetry, The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry, Solid Air, Stories of Perth and Going Postal. In 2015, SPM performed THE 24 HOUR PERFORMANCE POEM… which was exactly as it sounds. A mentor to many emerging West Australian poets and recipient of a 2019 KSP Writers Centre First Draft Fellowship, SPM is the coordinator for WA Poets Inc’s Emerging Poets Program.

Scott-Patrick Mitchell (SPM) is a non-binary West Australian poet, writer and spoken word artist. SPM’s work appears in Contemporary Australian Poetry, The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry, Solid Air, Stories of Perth and Going Postal. In 2015, SPM performed THE 24 HOUR PERFORMANCE POEM… which was exactly as it sounds. A mentor to many emerging West Australian poets and recipient of a 2019 KSP Writers Centre First Draft Fellowship, SPM is the coordinator for WA Poets Inc’s Emerging Poets Program.

Us Boys Made of Smoke

When we first kiss, I taste tobacco on your lips: rum-soaked ash, calling. For an ex-smoker, this kiss is dangerous. You are dangerous. But the sandpaper stubble of your chin smooths out the edges of my concerns. I sink into your tongue, lick the inside of my mouth. You turn my breath to smoke.

– Do you want a cigarette?

You ask this question after two months of dating. Two months of nicotine craving. These cravings are just as bad as the ones I have for you, for your kiss, for your nakedness heaving into my skin, into me.

– Yeah… ok. But you’re gonna have to roll it…

In time I learn your perfection of rolling a cigarette with hands too small to hold the volume of my lungs. My rollies are crooked, jagging yellow stains across the interior of the middle and index fingers. They are too tight at the tip, too loose at the base. The butts keep sticking to my lips. They aren’t as smooth as yours.

Like our cigarettes, we too are opposites. You: lithe slender man made of smoke, hair a caramel curl cupping collarbones, eyes so blue I am convinced you have stolen them from a work of art, or some long dead god. Me: scrappy, short, shoulders too broad, black stubble chin matching the buzz cut blackening my crown, eyes dark like a forest of hazel trees, squinting out the sun.

In bed, we are opposites again. My hands are confident. They turn your body into rollie papers succumbing to spit. Your hands have a nervous shake, as if desperate to light up, fumbling with how to keep a match aflame. My body is a flammable material so unfamiliar to you that it takes three months for you to learn how exactly to make me burn. I discover your trigger points in a matter of days, reduce you to sizzle. Then, embers.

Balance comes when you finally take the time to teach me how to roll a cigarette properly. In exchange, I show you the points on my body that ignite under tongue. We learn how to cup our physicality into the other. We are not spoons: we are the whole damn cutlery drawer. How we knife, fork, ladle love. Two cooks, our bed a broth. Smoking after sex.

– What do you mean you don’t know how to cook? you say, surprised at how barren my fridge is.

– I… just never learnt.

– So what do you eat?

– Take out. Cereal. Toast.

You try to teach me recipes you know, but all I learn is that meals are just a precursor to having another cigarette.

– You smoke too much, you say.

I just cough.

Somewhere, in the tendrils between us, an image settles into our lungs: black, sticky, uncomfortable. I want to jab a cigarette into our conversations, burn the skin of our speech, say you brought these back to me. But instead, I just exhale another plume into the room. The furniture is beginning to stink.

Outside of this house, smoking is more illicit, unacceptable. The bars in our town have gotten rid of designated smoking areas, so we smoke out on the street. We smoke in places less safe, more dangerous. Out the front of the bar on James Street is where it happens.

-Ya got a smoke?

The guy asking? He is trouble. Mr I’m-so-sketchy. Mr I-haven’t-had-a-decent-night-sleep-in-a-fortnight kinda trouble. His friend is all hollow cheekbones, rat-tail eyes skittering the sidewalk, looking for cigarette butts, opportunity.

These are the type of boys who would return home, hands blackened with ash, clothes stung with arson, only to tell their mother that no, they have no idea who started the bushfire over at the next farm.

You hand them your pouch of tobacco.

– Yeah thanks…!

The guys laugh. They begin to walk away, your pouch of tobacco in hand, their grins sinister, mocking. The f word is hurled from both their mouths – Molotov cocktails hitting piled sticks – jeered and jeered again at us. Scrappy flames flick up my skin. Anger kindles inside me.

– Oi, give it back! I yell, stomping toward them.

– Or what?! The one holding your pouch snarls, squaring up. What ya gonna do, you fucking faggot!?!

More slurs burn up from their throats – pooftas, cocksuckers, AIDS junkies – and are hurled at us. I allow myself to combust. You see, the rage is always there. Part of you learns to live a moment away from being lit up. These bigots just open the door, allow the fireball to come through, glorious. Consumptive.

I reach for your tobacco pouch. Their ashen hands push me back. I mimic their movement, push the ringleader, hard, then his mate, harder. The fire in their faces is furious. I don’t see their fists swing toward me. But I feel them. I hear them. Blood fills my mouth as my nose cracks. I spit the fluid out, not realising I’m spraying these thugs with my blood. They almost wail, beseech. More fists come.

I take them. Do not buckle.

You don’t come to pull me away. You don’t even shout out in protest. You just shrink inside yourself. Something extinguishes inside of me.

Encroaching sirens scare them off. They scuttle, scurry, run. Like rats. Like vermin.

This is when I buckle, slump to my knees. I can feel all eight punches. You rush toward me, but the blood covering my face, my clothes, it halts you, as though you’ve been conditioned to fear the very thing that makes us pump. Not even your hand reaches out to calm me.

I begin to sob.

The police arrive a minute later. You kneel beside me, put an arm around my shoulder. There is no comfort in this.

In the days that follow, I learn that bruises heal but a broken nose is for life. Especially if you’re on welfare. I flinch under your touch. You don’t meet my gaze. I jump when you enter the room. My anger, undiminished, makes me pull inside myself for warmth. One night, drunk, I extinguish a cigarette on myself while you watch.

– What the…!? You exclaim, panicking, slapping my hand away from doing myself harm.

I just grin. I want you to hit me, again.

In the days that follow, I purposefully antagonise you. You make excuses to stay away, stay at yours, stay on the other end of chat and telephone. You take longer and longer to respond. Our love turns to smoke.

I throw out my cigarettes, my ashtrays, all the paraphernalia of flame you helped me bring back into my life. The burn mark turns to scar. My broken nose becomes familiar. Everything we have created together is unlearned.

The cops never catch those two thugs.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

On Being a Working-Class Writer

How does a working-class girl from the council estate become a poet? And what’s class got to with it anyway? What does it mean to be a working-class writer? Can I still be a working-class writer now that I work in a university? What do working-class writers write about? Answering these questions requires a story.

I became a writer by accident. When I was at school I wanted to be an artist. I loved art – my brother and I were taken to London art galleries quite often when we were growing up. Bus fares were cheap then and the galleries were free. My Dad was always looking for places outside of Walthamstow to take us out at weekends and holidays because my Mum worked night shift and was the breadwinner. Dad was an autodidact – a working-class man who taught himself how to paint and draw. He worked (when he was employed), as a self-employed sign writer and our flat always smelt of paint and turps. Dad died when I was young and Mum was too busy trying to keep us fed and housed, so as soon as I was old enough, I took myself into central London and visited the galleries again.

They became my happy places. At school I studied art, but there was no chance that a kid from the council estate was going to become an artist. So I left school and worked in retail.

I had always been a reader. We had books in our flat (1) – Dad read spy novels and racy thrillers. Mum never had time to read when we were young, but she told me that when she was a child she loved to curl up with a book, but would get told off for being lazy by her father (a London Transport bus driver). No one in her household had spare hours for reading – everyone had to work. Mum’s schooling was interrupted by WWII, and despite her wish to continue at school and study to be a nurse, she had to leave at 15 and get a job. I didn’t see her read a book until I was in my teens (although she always did the newspaper crossword). She began reading again when a mobile library started visiting our estate. She liked historical romances, especially those set during WWII. Until her eyesight failed in her 80s, she always had a book on the go.

As a child I spent many hours in libraries. I’d read anything, which is typical of working-class readers. There was no sense of what might be ‘good’ or ‘worthy’ literature. Any book blurb that looked interesting was added to my pile. My local library had an excellent collection of Caribbean and South Asian literature and I worked my way through everything on the shelves. On a school excursion I saw Dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson (2)

perform. His work showed me that I could write poems using my voice (I didn’t have to sound like Wordsworth or Tennyson – poets we read at school). This was a life-changing experience and the revelation that a non-posh voice could be valid stayed with me. At my working-class high school in the 1980s we had a visit from poet Carol Ann Duffy (3). None of us knew who she was, but a few from the English class went along to her workshop. This turned out to be another revelation. She knew how to talk to us working-class girls and she told us that our stories mattered. A poet from a poor neighbourhood like ours who understood our lives. It was clear to me from then that poetry was for everyone.

This love of poetry and of reading didn’t take me to university though. That was far from my reach. My dream of being an artist faded with the reality of leaving school and I started working full time at Hamley’s of Regent Street(4). I kept on reading (anything); I wrote poems in a notebook and created comical biographical poems for my co-workers between short snatches of time between customers on till roll). I carried on writing poems that I showed no one for years. After leaving Hamley’s to travel with a baby and partner in tow, I carried on writing but never considered publishing my poetry, although I gifted a few friends biographical poems about them. We travelled in our Kombi van around the UK and Europe and then left for Taiwan. I taught English in Taiwan with no qualifications (and likely was responsible for a cohort of Taiwanese kids with Cockney accented English).

Eventually I ended up in Australia with my Australian partner and child and we decided to ‘give uni a go’. When choosing what course to apply for I realised that the thing I’d actually always done consistently since I was a child was write poems and stories. My aspirations to be an artist gradually changed into wanting to be a writer, so I enrolled in a creative writing having little idea of what to expect. I’d never been on a university campus, and my understanding of tertiary education was formed through film and TV. I was required to submit a portfolio of writing with my application and I collected up all the things I’d written over the years and typed them up on a library computer (I couldn’t type – this process was excruciating. I was one of the only girls in my high school who didn’t take typing as an elective). I was called in for an interview at the university and told by the interviewer that my work had ‘potential’ – I had no idea what that meant.

I was accepted into the course and discovered that what I loved to write about was my experiences of being working class. Of my old home in London, my family, friends and the working-class community that I’d left so far behind in England.

My writing was well received by my tutors at uni and they were very encouraging and supportive. The first poems I started to get published in the late 1990s were centred on life on the council estate I grew up on, and by the end of my undergrad degree I had a collection in print (5). I incorporated Cockney songs into some of these early poems and enjoyed performing them to an Australian audience. I read at venues across Sydney and interstate. I even had a spot at at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in 2001. I was starting to make a bit of a name for myself but there were obstacles. I experienced dismissive and patronising comments from some well-established Australian poets. It was at this time that I realised that the gatekeepers of the Australian literary establishment were generally not interested in, or sympathetic towards, working-class poetry. So I started a PhD (6) investigating the lack of working-class representation in contemporary Australian poetry and discovered that working-class poets had been shut out of the literary mainstream. They found their work dismissed as simplistic or didactic. As sociological or overly political. Lacking in literary technique – not enough use of metaphor. Too focused on the everyday, the mundane. I saw it differently. Working-class poetry was full of life. It was about collective experience. There were poems that focused on hardship, poverty, trauma. Life living hand to mouth. Struggle was common. But there was also celebration of community, of working-class culture, and working-class diversity. The poems were often funny and the poets used humour as a survival tool. The language was simple, not simplistic. And metaphor might have been used sparingly, but that was because the poets wanted to represent the reality of their everyday lives – working class life often didn’t have time for metaphor.

The poets I talked to at the time had all found it very difficult to get published in mainstream literary journals. Many were very popular in their home towns, and drew large crowds to readings. Some self-published and sold many books on their own. Not many found their work reviewed in literary magazines, and they preferred to read at local events in pubs or worksites rather than literary festivals. Aside from a few notable exceptions, the Australian literary establishment gatekeepers were not interested in working class poetry. Or other working class writing. At this time (2000-2007), they were not interested in class at all, and this was a sentiment shared by academia too. As I started my academic career (as a casual academic for the first ten years), I began a battle with academics to recognise class as significant in Australia. I was told that class wasn’t a ‘thing’ in Australia, and I should leave my British class hang-ups behind. I was accused of having a class chip on my shoulder and asked when I was going to ‘get over the class schtick’.

But you can’t ‘get over’ being working class. It’s possible to hide a class background and learn to speak like middle/upper class people. An accumulation of educational and cultural capital can help with the passing. This means a rejection of family, friends, communities though. A class betrayal. Certainly not my intention. My working-class background has shaped me. I learnt how to survive hardship, to make the most of what you have. To always be ready to help others, to stand up for yourself and your community. My mother taught me these values. She kept us fed and clothed and kept the ‘social’ from the door. I watched her stand her ground in the DHSS office when they refused her emergency payments. She saw off bailiffs and loan sharks. She recognised who was at fault – the government, Thatcher in particular and later, all politicians who cared about making themselves richer. My mother looked after her neighbours and when she needed help, they looked after her. When I wrote my first collection of poetry, she was a big feature – a persona based on her was very important to the collection.

My working-class background is my old school, work friends, neighbours. It’s the council estate I grew up on, concrete playgrounds where I skinned my knees, the local newsagents where we bought sweets. Pubs I went to as a teenager, the street market, local caffs (cafes). Buses I rode, libraries I trawled. It’s everything. I’m proud of my working-class background. My university education and my academic job has not stopped me from being working class. I am a working-class academic. I am fortunate to now have a continuing position and earn a respectable salary, but that’s where my economic capital ends (no inheritance – my mother lived in a council flat until she died). I accumulated cultural capital as an autodidact before starting university as a mature age student. But I don’t have knowledge of the ‘classics’ like many of my middle-class colleagues. Middle-class pursuits are mostly not for me. If there is a working-class play being performed I might go see it, but I’m not interested in bourgeois theatre productions. Films are more my thing – and my love for independent, global art house cinema started off as a working-class teenager looking for cheap entertainment in central London after school (art house cinemas offered good concessions). If I go to a pub, I like one that sells Carlton Draught rather than micro-brewery craft beers. I resent paying more than $5 for a glass of wine that I don’t even like. I watch TV – lots of it. And I don’t have ‘guilty pleasures’. If I watch Love Island, it’s because I like it, not because I’m watching it ironically.

Things are changing. Not necessarily in the world of literary journals in Australia, but more widely. People are interested in class again (7). After all the years of working-class academics and writers ‘banging on’ about class, people are starting to listen. There is a growing volume of Australian fiction set in working-class communities. Books such as Peter Polities’ Down the Hume (2017), and The Pillars (2019) Luke Carman’s An Elegant Young Man (2013), Felicity Castagna’s The Incredible Here and Now (2013), Omar Musa’s Here Come the Dogs (2014), Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s The Lebs (2018), Tamar Chnorhokian’s The Diet Starts Monday (2014), Claire G. Coleman’s Terra Nullius (2016), Sue Williams’ Live and Let Fry: A Rusty Bore Mystery (2018) and Enza Gandolfo’s The Bridge (2018) show the ways in which class intersects with race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and religion.

Melissa Lucashenko’s Too Much Lip won the 2019 Miles Franklin award. The 2020 Sydney Festival includes Anthem – a play centred on working class characters written by Christos Tsiolkas, Andrew Bovell, Patricia Cornelius and Melissa Reeves. And I have a contract from a publisher to write an academic book on Australian working-class literature.

It’s hard to crack the literary journals though and in Australia there still isn’t a lot of working-class poetry appearing. It isn’t clear why this is the case, and I’ll be investigating this as part of my new research project. The working-class poets I included in my PhD, have mostly stopped writing. Cathy Young, from South Australia had one book published in 2004, but nothing since. Her partner and fellow poet Martin R. Johnson published three collections, but also stopped publishing in 2004. One of the poets who was most prolific at the time was Geoff Goodfellow (also from SA). Goodfellow last published a book in 2014, with a self-curated collection of previously published poems. He hasn’t published any new works since 2012. While I haven’t had a chance to catch up with the poets yet to ask why, it is clear that they were rarely published in Australian literary journals. Young and Johnson concentrated their efforts into publishing locally, and Goodfellow focused on publishing collections with small sympathetic presses such as Vulgar Press (now defunct) and SA Wakefield Press. Most of the other poets in my PhD published sporadically and then disappeared.

A quick survey of 2019 issues of some Australian literary journals reveals some working class poetry. Mykaela Saunders in Cordite with ‘For Cops Who Stalk Children on Houso Estates’ (8). Her poem shows how class intersects with race and gender. In ‘Those Days in the Dirt’ (9) from the same issue of Cordite – Tom Lewin’s narrator reminisces about his days as a manual labourer and the company and camaraderie found among working class men. There are some poems written about working class grandfathers, and there is also some class fetish. Ian C Smith’s ‘Sanctuary’ paints a picture of a homeless man, but the man is observed from a distance – he could be local wildlife. I haven’t come across much in Overland or Meanjin etc lately, but I need to keep digging. Melbourne poet Pi. O. has published a new epic 500 page poem, Heide with Giramondo. Pi. O.’s work has always focussed on working class life, but his obscurity means he is not often featured in the literary mainstream.

So why is working-class experience mostly absent from contemporary Australian literature? What are the reasons for the middle-class domination of the literary scenes? What is the potential impact of the lack of representation? How can this lack of representation be addressed?

Working-class literature is important, not just because it is the literature of marginalized people, but also because it includes a diverse array of literary styles, techniques and forms. At the same time, there are some commonalities that can be identified and which mark it as belonging to its own specific genre (10). Working-class literature is therefore a rich source of writing and there are various ways that working-class literature can be analysed. This analysis can also be framed around a series of questions; how does working-class writing engage with the working-class vernacular? Is there a sense of working-class culture that runs through the works? How does this manifest? Does work (or unemployment) feature in working-class writing? How is working-class literature political? Are politics explicit in the works or embedded in representations of the everyday for working-class people? And is the diversity of the working class and working-class experience represented?

I’ve been asking these questions for a long time, and every time I encounter some working-class writing, I find myself asking them all again. I have some answers. Working-class experience is missing from contemporary Australian literature because the gatekeepers have been middle class and not interested in working-class life. This middle-class domination is enabled due to structural privileges. Middle-class people are more likely to have university degrees than their working-class counterparts, and are more likely to have degrees in the arts, and to seek work in the creative industries. A lack of representation means that working-class people are not seeing their stories told – this reads as a cultural signifier that working-class experience is not important nor a worthy subject for literature, especially poetry. To address this lack of representation requires more working-class background people in gatekeeper roles, and a willingness on the part of middle-class editors to publish working-class writing.

To answer the questions that frame analysis of working-class writing is easy. Working-class writing employs a working-class vernacular, and poets use the colour of slang and dialect, and the rhythms of everyday speech in their work. Various elements of working-class culture run through the poetry – this includes working-class pastimes, food, popular culture and the more general culture of collectivism. Working-class poets write about work in all of its forms; manual labour, routine white-collar work. They write about precarity, about bastard bosses, unemployment, fighting Centrelink, union power and the camaraderie of work mates. Politics is embedded in working-class writing. If a poet comes from a working-class background and writes from a working-class perspective, then the poems are inherently political because they are published against the odds. And working-class writing reflects the diversity of working-class people and challenges the media representations of working-class people as white, blue collar male workers.

What would I like to see? Poetry that engages with the working-class everyday. This is poetry that doesn’t hold back, that reveals struggle, but also the positive aspects of working-class life. Writing about struggle works best when it’s been experienced first-hand, otherwise it easily turns into poverty porn. The working-class poetry I would like see is written by poets who understand how class works and how it intersects with race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality, ability. This is working-class life. It is diverse. Working class people are not a homogenous group. But there are shared understandings, commonalties such as bosses who exploit, economic insecurity, the fight for decent housing, education, health care. There are differences too – white working-class people experience class discrimination, but not racism. Working-class women often find themselves on the receiving end of sexual harassment at work (and can feel powerless to report). LGBTIQ+ working-class people can feel marginalised in some working-class communities. Working-class disabled people face daily struggles due to expenses involved in accessibility. I want to see all of this in the poetry that is published in Australia. Poetry written, by, for and about working-class people. Class is in vogue again, and hopefully this interest in academic work, memoir and commentary will spill over into poetry and emerging working-class poets will feel inclined to submit their work and show through poetry the struggles faced when working class. If anyone had told that girl from the council estate that one day she would be an academic and a published poet she probably would have laughed. The more that working-class poetry is published, the more likely it is that working-class young people will see literature and art as real possibilities and worth pursuing. And so, I remain optimistic.

Citations

1. bell hooks points to the importance of books in working-class households as paving the way for education and the potential transformation that comes with formal education, hooks, b. (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom, New York, Routledge, p 127

2. http://www.lintonkwesijohnson.com/linton-kwesi-johnson/

3. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/carol-ann-duffy

4. Hamley’s is a very famous toy shop in Central London.

5. The thesis is available online: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/2100/615/2/02whole.pdf

6. Hope in Hell (2002), published by Five Islands Press

7. For a good introduction to Working-Class Studies, see Linkon, S. L., Russo, J. (2005) New Working-Class Studies, Ithaca, Cornell University Press. For books on working-class literature see, Zandy J. (1990) (ed.) Calling Home: Working-Class Women’s Writings, an Anthology, Rutgers University Press and Fitzgerald, A., Lauter, P. (2001) (eds), Literature, Class and Culture: An Anthology, New York, Longman, Goodridge, J., Keegan, B. (2017) A History of British Working Class Literature, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, Coles, N., Zandy, J. (2006) American Working-Class Literature: An Anthology, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

8. http://cordite.org.au/poetry/peach/those-days-in-the-dirt/

9. http://cordite.org.au/poetry/peach/for-cops-who-stalk-children-on-houso-estates/

10. Zandy J. (1990) (ed.) Calling Home: Working-Class Women’s Writings, an Anthology, Rutgers University Press

SARAH ATTFIELD is a poet from a working-class background. Her writing focuses on the lived experiences of working-class people (both in London, where she grew up and in Australia where she lives). She teaches creative writing in the School of Communication at UTS. She is the co-editor of the Journal of Working-Class Studies.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Flood Damages

Flood Damages

by Eunice Andrada

Giramondo

ISBN: 978-1-925336-66-5

Reviewed by DARLENE SOBERANO

In her debut poetry collection, Flood Damages, Eunice Andrada never explicitly mentions the words, ‘New South Wales.’ Nor does she name ‘Australia’ in any of the 37 poems.

She opts for restraint, often using the word ‘here’ as a substitute for the name of a place. This can be seen in poems such as ‘autopsy’: ‘I complain about the weather here, / how the cold leaves my knuckles parched’; and in ‘Marcos conducts my allergy test’: ‘Maybe he grew up here and my accent isn’t quite / right yet, so he can’t understand me’. I am reminded of André Aciman’s essay, Parallax. Aciman details his ‘dreaming’ of Europe while living in Egypt and he declares, ‘Part of me didn’t come with me. Part of me isn’t with me, is never with me’. He eventually comes to this conclusion: ‘I am elsewhere’. For Andrada’s speaker, the exact place isn’t as important as the fact that it is elsewhere; that it is not the Philippines.

The most explicit name for ‘Australia’ I find in Flood Damages is in ‘alternate texts on my aunt’s lightening cream’: ‘o oceania your body an apartment block / cracked under the spanish the british the / americans the japanese the americans’. Here, even, Australia is referred to within the context of a group. Restraint as technique in poetry can often lead to a tepid vagueness, the poet invulnerable and hiding in the text. In Andrada’s hands, restraint is transformed into a compelling exploration of absence. By omitting Australia, Andrada leaves space for memories and dreams of the Philippines to fill in.

In ‘(because I am a daughter) of diaspora’, Andrada writes in water images to capture the sensory experience of moving through the Philippines—a country made up of over 7,000 islands. Water, for the poem’s speaker, becomes the sensory experiences through which all associations flow, even if she is not there. The ‘daughter of diaspora’ is ‘by default – / an open sea’, whose mother is shamed in their not-Philippine country; ‘They convince my mother / her voice is a selfish tide, / claiming words that are not meant / for her’. The ‘carcass of ocean’ makes ‘ragdolls’ of the speaker and her mother’s ‘foreign limbs’, an image that is immediately followed by this declaration: ‘In the end / our brown skin / married to seabed’. Here, water is a force that drowns as much as it is a force capable of returning the speaker home.

Most Filipinx immigrants flee the Philippines in search of ‘a better life’. Andrada offers two main explanations in Flood Damages: dictatorship (‘Marcos conducts my allergy test’) and displacement due to climate damage.

In ‘(because I am a daughter) of diaspora’, Andrada’s speaker, having fled the Philippines, looks back and discovers the loss of belonging, which is marked by the loss of language:

‘When I return to the storm

of my islands

with a belly full of first world,

I wrangle the language I grew up with

yet still have to rehearse’.

A ‘man in rags’ stops the speaker and asks her ‘in practiced English’ a question: ‘Where are you going?’ This question makes the speaker want to plead to him, ‘We are the same. / Pareho lnag po tayo’. Frantz Fanon wrote in Black Skin, White Masks that ‘mastery of language affords remarkable power’. In ‘(because I am a daughter) of diaspora’, the speaker is sensitive to the absence of language and therefore the absence of power. The difference between ‘the man in rags’ and Andrada’s speaker is so heightened that the speaker is made aware of even ‘the dollars in [her] wallet’—paper money, which is supposedly quiet, yet the speaker can hear them ‘sing another anthem’.

In contrast, Andrada examines communication between mother and daughter in the poem, ‘rearrangement’. In ‘rearrangement’, Andrada peers at the gap between two languages, Tagalog and English, and at two figures who each have different masteries of both of these languages. The mother pronounces ‘too hot’ as ‘too hat’, says ‘open the lights’ instead of ‘turn on the lights’. In contrast, the speaker struggles to say ‘hinihingal’, a word that means, ‘to be gasping’. ‘Hinihingal’ is pronounced in such a way that mimics a gasp; it is almost an onomatopeia. When the speaker ‘disfigures the [word] in [her] mouth’, it is struggle upon struggle; the speaker gasps twice. When the speaker and her mother are in conversation with one another, they constantly ‘mistranslate’ their words and phrases. Mistranslation should expand the gaps between mother and daughter. For Andrada, it is instead a site of wonder: ‘what careful, imperfect truths / we have birthed in this prose of error / and say it again, please’. There is no gap. When they speak, they are ‘saturating one language with another’.

Andrada achieves a similar effect in ‘harbour’. She writes: ‘Pasa sounds like the word / for soaked’. Pasa means bruise; the word it ‘sounds like’ is basa, which can also mean to read, depending on the way it is said. In other words, if there were no difference in the way that soaked and read were conjugated in Tagalog, to read could also mean to make wet. My personal grasp of Tagalog is limited. It is not a language of my present; it is the language of my childhood, with its psychic tendrils touching everything. In my particular linguistic landscape, basa is wetter than soaked; pasa is said quickly, so it is less distressing than bruise. The quickness of pasa also imitates the way in which the bruise might have been formed—object colliding with body. In this way, pasa can almost sound like a verb.

Fanon also wrote in Black Skin, White Masks: ‘To speak means to be in a position to use a certain syntax, to grasp the morphology of this or that language, but it means above all to assume a culture, to support the weight of a civilization’. Language is a tool with which we learn the stories of our lives and our histories before we were possible. The possibility of a voice, saying, This is where we lived. This is where home is. It will always be here. This is how we fell in love. This is why we left each other. This is how we appear human to one another, which is why the forced absence of a home, a site of history, is dehumanising.

The question, ‘Where are you from?’ is a question that many immigrants encounter anywhere—everywhere. A train, a bar, a classroom. In her poem titled, ‘where are you from?’, Andrada answers the question uniquely in two lines:

‘a woman’s ribs / cheating grandfathers /

the confession box / floodwater’.

Here, Andrada writes a complete and complex personal narrative with her first three answers. The tension between them are heightened by virgules. Each virgule reveals the building frustration of the speaker. Andrada ends ‘where are you from?’ with the answer, ‘floodwater’, a resounding word among sentences of the personal. This emphasis works as a reminder that the Philippines is a country that endures severe damage from typhoons year after year. Homes have been drowned, lives have been lost, important family artefacts have dissolved in water. Andrada’s poem, ‘photo album’, then, reads as a firm artefact against erasure—and yet, it is a poem full of physical silence. In it, the speaker imagines many different lives. She imagines her mother’s life in other countries. She is away working as an Overseas Filipino Worker. ‘photo album’ is constructed with sprawling white space, as if silence is Andrada’s true form and language is the failure. Language fails because it is not an alternative to the mother’s presence in the speaker’s life. The speaker’s yearning is so wild that, in her imagination, cities and bodies become equally large: ‘Abu Dhabi, 2009’ and ‘Singapore, 2001’ are captions just as, ‘across ribs, 1998’, ‘on subject’s cheeks (seen above), August’, and ‘pupils, March’ are captions. Similarly, in ‘soft departure’, Andrada constructs a space between every line as such:

‘earlier that day

she mashes chicken liver

into sliced bread

picks us up from school

commits no crimes’.

Viktor Shklovsky once wrote that ‘art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony’—that is, to defamiliarise the reader out of habitualisation, which can ‘[devour] work, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war’, and which can, as Shklovsky hints, help to normalise daily oppression. To make the stone stony is to undo the damage of habitualisation. Andrada never writes the word ‘deportation’ in ‘soft departure’. She writes around it, defamiliarises it, refuses to make it another overlooked part of daily life. There is ineffable grief within the many absences in this poem. It is necessary for language to fail, here, so that its failure may leave room for the mother’s return.

Absence in Flood Damages is striking because the book is a physical item. It can be found at a chain bookstore, like Dymocks. It can be found at independent bookstores, like Better Read than Dead, or Hill of Content. It has been shortlisted for the Victorian Premier Literary Award for Poetry in 2019, it won the Anne Elder Award in 2018. Flood Damages is a sizeable presence in the world. It is an artefact that floods cannot destroy. And in it, Andrada tells her many histories—personal, family, country—with lush, specific detail. It is an artefact against forgetting that brown immigrants and their brown families are people. In Flood Damages, that which is human in immigrant families cannot be taken away, despite all efforts to do so. For Andrada, cruelty is decidedly not the point, but its opposite: a tenderness that endures across oceans.

References

Aciman, André. André Aciman: Parallax. FSG Work in Progress, https://fsgworkinprogress.com/2011/10/13/andre-aciman-parallax/.

Andrada, Eunice. Flood Damages. Giramondo Publishing Company, 2018.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Pluto Press, 1986.

Shklovsky, Victor. Art as Technique. The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, 1917.

DARLENE SILVA SOBERANO is a Filipino poet. Their work has appeared in Mascara Literary Review, Australian Poetry, and Cordite Poetry Review. They tweet from @DLRNSLVSBRN

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

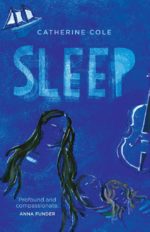

Sleep

Sleep

By Catherine Cole

ISBN:978 1 76080 092 5

Reviewed by Julie Keys

‘Will You forgive me?’ Monica asks her daughter, Ruth, in the opening paragraph of Sleep.

‘Forgive?’ I thought. What is there to forgive?’ (1)

As a child Ruth does not understand the angst behind her mother’s question and is dismissive of it. The memory, however, leaves an indelible mark, one of many that resurfaces as she tries to understand her mother’s life and her death.

Ruth is seventeen and a schoolgirl when she meets the elderly French artist, Harry, in a café in London. There is a bond, a recognition of similarity in one another as they converse. Both have experienced trauma and loss. Ruth’s mother has died, and Harry grew up in Paris before and during its occupation in World War II. It is in sharing their stories that a friendship is formed.

Ruth and Harry’s tales intertwine. Author Catherine Cole takes us back to Harry’s childhood in Paris, to the quirks and allure of life beside the Canal St Martin. We hear the voice of his mother calling him from a fourth-floor window. There is his aunt’s cello, his fascinating and vibrant twin cousins. We witness the exact moment Harry stands beside his father observing a painting and decides he will become an artist. This comfortable and contented life sits alongside a shifting political climate. Some ignore the changes but the more vigilant escape Paris and France while they have the chance.

Like Harry, Ruth talks about her family. The resilience of her sister Antoinette and her father, family outings, the sleep therapy that had been the treatment of choice for her mother’s depression as a young woman, and the mother she knew with her increasing propensity for sleep: ‘She’d begun to sleep anywhere: at the kitchen table, on a blanket in the garden, on any one of our beds’ (133).

Trauma, loss and shared memories are not new subjects for Cole. The author of nine books, her work reflects a range of interests and eclectic skills that includes fiction, non-fiction, memoir, literary, crime and short stories. Sleep is an extension of the themes of love, migration, forgiveness and refuge first explored in her short story collection, Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark (2017), shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards in 2018. Just as the impact of an elderly artist in the life of an up and coming student was initially examined in the author’s memoir of her friendship with A.D. Hope in The Poet Who Forgot (2008).

Skill and experience are put to the test in Sleep as Cole delves not only into the complexities of these issues but steers away from a traditional plotline – a choice that highlights the novel’s intricate themes and serves the narrative well. This is Ruth’s version of events, her recollections. She narrates the story from a present-day visit with her Great Aunt Elsie and from the safe haven of the Yorkshire Dales. The plot emerges via a kaleidoscope of memories, beautifully rendered passages that draw the reader into each moment as the story finds its shape and unfolds.

Elsie is a natural counterpoint to the memories that consume her niece. She is lucid, sharply outlined, rooted in practicality, a contrast to Ruth’s mother Monica and her torpid life. Elsie has her own memories of Monica, revealing previously unknown layers to Ruth. She moves around her house and Ruth’s life ‘setting things to rights’(32). There are pots of tea, the smell of lavender, stories about the war and the depression. She bids Ruth not to spend her time on Harry’s stories at the expense of her own and warns, as her mother once warned her to ‘be careful what you remember and when’ (33).

Cole brings a familiarity to the settings – London, pre-war Paris, and the Yorkshire Dales – and is tender in her portrayal of Monica, ‘a shadowy figure behind the door, a lump of sadness on the battered couch, a pair of long white feet under a red and purple hippie skirt. Hair across her face, she weaves, moans’ (161). But Sleep does not always follow a comfortable line. As a reader, I felt unsettled over Ruth and Harry’s meeting. Was it really the result of chance? There was also some discomfort in observing Ruth and her growing obsession with unravelling Monica’s past as she tries to forage out those who might bear some responsibility. As in life, nothing is straight forward and moments of ill ease provide fuel for reflection.

Harry reminds us that despite trauma there is the possibility of resolution. For him art is the healing salve, the restorative that has provided some balance to what has happened in his life: ‘Art allows us to make something lovely of self-delusion and pathos and longing and fear.’ (105). Harry is his most persuasive as he encourages Ruth to find the art in her own life. The conversation between the older Harry and the younger Ruth who equate with the past and the present, threads its way through the narrative debating the conundrums. Can we always forgive regardless of the circumstances and is consolation a worthy alternative to justice?

Harry argues that; ‘You must forgive. Revenge hurts only those who desire it’ (63), all the while understanding that it is Ruth’s decision to make.

In her acknowledgments Cole describes Sleep as ‘a generational conversation about art and loss [that] speaks also of the need to ensure that we learn from history by understanding how easily past horrors can resurface while we sleep or turn a blind eye.’ (246). In this sense Sleep is a timely novel that extends beyond the last page as we ponder the shifts in the world around us and contemplate how our own somnolence has contributed to the social, environmental and political catastrophes that to some degree we now live with and have come to accept.

JULIE KEYS has recently completed a PhD in Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong. Her Debut Novel The Artist’s Portrait was shortlisted for the Richell Prize for Emerging Writers in 2017 and published by Hachette in 2019.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Nadine Schofield is an emerging writer living in Wollongong. She is a high school English teacher helping young women find the magic of words and the power of their own story. Nadine is completing a Master of Writing at Swinburne University.

Nadine Schofield is an emerging writer living in Wollongong. She is a high school English teacher helping young women find the magic of words and the power of their own story. Nadine is completing a Master of Writing at Swinburne University.

Serenity

‘As I begin to write now a feeling of peacefulness comes over me as if I need not for inexplicable half-hidden reasons refrain from writing any longer… it is often not possible to write about events until they are over or sufficiently of the past, … secrets, if they are revealed completely, become mere facts, something extra to real life.’

—Elizabeth Jolley, The Vera Wright Trilogy

* * *

I was thirty-eight. We had been married for two months. And then we were going to be parents.

What to Expect When You Are Expecting (Murkoff) became our manual, our source of wisdom. In his radio voice, Colin would read aloud from the couch the weekly update of what was happening inside my body. A strange food motif runs through the week-by-week descriptions:

Then the fruit was replaced with a heartbeat; the ‘lub-dub’, a ‘fetal symphony’ (Murkoff 181).

* * *

The Women’s Ultrasound and Imaging Clinic is behind a working construction site; a single level red-brick building with long corridors of brown carpet illuminated by exit signs at regular intervals. The smell of concrete dust is cut through with disinfectant. We find the right door to the right waiting room and, after repeating names and dates and numbers, we are called into the imaging room by a young nurse. The room is a cave, illuminated by two computer monitors and a dimmed light over the bed. The nurse is friendly, and the directions come quickly.

‘Everything off from the waist down. Up on the bed and I’ll put this over you.’ She is holding up a sheet of paper. I am embarrassed to be pulling my pants down in front of my husband and a stranger.

The purpose of the ultrasound is to date and confirm the viability of the pregnancy via a transvaginal examination. The nurse sheathes the transducer with a condom and cold gel and asks me to spread my legs. Colin and I watch the shadowy, swirling mass appearing on the monitor until the nurse ends the guessing game and we hear the baby’s heartbeat: a fast, rhythmic sound like a wobble board.

‘155 beats per minute, but that’s normal,’ she informs us before withdrawing the probe.

* * *

What did we hear? What is a heartbeat? Any medical textbook defines the human heart as an electrical system; the heartbeat is the sound of ‘atria and ventricles at work pumping blood’ (Clinic). In these terms, the human heart becomes a switch, a light that can be turned on and off. The Oxford Dictionary defines the heart as evidence of ‘one’s inmost being; the soul, the spirit’; ‘the seat of love and affection’ (“Heart”, 879).

We made a heartbeat.

We take each other’s hand and with the sun in our eyes we walk back to the car, our large white envelope in hand. We haven’t expected a photo, not so soon, and we sit in the car looking at our shadowy mass with three straight arrows pointing at it, so we know where to look. Is this going on the fridge?

‘We made a heartbeat,’ I whisper as I turn to face Colin. And there he is, a father. He has become a photograph, caught shirtless with our child curled into the wiry, grey hairs of his chest, head lowered, and eyes half closed.

* * *

At the worst moment, What to Expect When You Are Expecting becomes our doctor. There is a chapter on miscarriage. ‘Signs and symptoms can include cramping or pain, heavy vaginal bleeding, similar to a period’ (Murkoff 534). In Emergency I cannot speak. I go to the bathroom several times to check that we need to be in Emergency. Parents come with vomiting children, bruised children and bleeding children. Colin and I sit in silence.

I answer the questions of a trainee nurse about my pain and when it started and how many hours and my periods and how many pads and then Colin is asked to wait outside.