Visions of China: Ouyang Yu’s Translations of Contemporary Chinese Poetry by Tina Giannoukos

Subscriber Only Access

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Accessibility Tools

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Middle of the Night

Middle of the Night

by HC Hsu

ISBN 978-0-9904287-4-9

Reviewed by PAUL GIFFARD-FORET

HC Hsu’s essay work, Middle of the Night, is part of what might be called Asian American experimental literature, that combines elements pertaining to the migrant experience with avant-garde forms and styles of writing, such as prose poetry, without subsuming the one under the other. As Dorothy Wang argues in her book Thinking its Presence: Form, Race, and Subjectivity in Contemporary Asian American Poetry (2014), the error would be to “read the experimental as experiential” (164) and hence fall back into the content-oriented approach that consecrated canonical Asian (American) diasporic literary fiction such as Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior or Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. To start with, Middle of the Night employs the essay form, a “minor” literary genre working at the crossroads between fiction and non-fiction, the anecdotic/personal and metaphysical/universal. The book’s plasticity — its hybridity — seems to befit Hsu’s overall purpose, viz. to narrate one’s individual musings from sunset (18:03) till sunrise (05:25). So the book is not divided into chapters but into slices of time, rather, reflecting Hsu’s concern with the minutiae of existence. Hsu’s attempt at jotting down those little epiphanies, fleeting moments, small joys and silent pains that fill up our lives, is like a photographer’s effort to capture a pose’s pause. The vanity of such an endeavour is, paradoxically, what makes the reading of Middle of the Night a deeply moving experience. It reminded of a movie scene from the American drama The Hours (2002), partly based on Virginia Woolf’s life, in which Clarissa Vaughan (Meryl Streep) has to listen to her former lover and dying friend Richard (Ed Harris): “I wanted to write it all. Everything that happens in a moment. The way the flowers look when you carry them in your arms. This towel – how it smells, how it feels … its thread. All our feelings – yours and mine. The history of it. Who we once were. Everything in the world. Everything mixed up. Like it’s all mixed up now. And I failed.”

Failure at embracing an all-encompassing truth, as the philosopher Jacques Derrida intimates in his work, is in fact constitutive of the deconstructive process. Things move slowly in Hsu’s book, if they move at all, just as thought sometimes works, running in circles, or the way memory functions, through fragments that do not always match up; yet at the same time, everything vibrates in it with the shrill of intent. Hsu’s highly dense, (in)tense prose aggregates clauses or word clusters that, to paraphrase the postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha in his seminal text The Location of Culture, “add to” but “need not add up” (1994, 155). Hsu’s descriptive insight and eye for details seen from a multiplicity of takes, through close-ups or low-angle shots, confers on his writing a cinematic quality that appears suited to his Romantic task of reviewing the world from a fresh perspective. As he states: “To find the miraculous in the ordinary, in the spectrum of the in-between, I think, is my ‘homework’” (108). For Hsu, the object of writing itself stands for this in-between miracle (miraculous in being precarious) whereby reader and author meet across space and time. To paraphrase Bhabha again, writing then consists in the task of measuring “how newness enters the world” out of this three-dimensional (con)fusion of souls between reader, author, and text. Three images in particular from Hsu’s story fragments have retained my retinae’s attention here.

The first image is from a TV documentary aired in the middle of the night, when insomnia makes you watch anything, like soap operas, reality shows or animal documentaries. Here, Nature’s little wonders take the form of a one-thousand-pound man being airlifted in his bed to the nearest hospital for gastric surgery. Reminiscent of an angel, is the surreal vision of this anonymous man’s ascent into the sky, as if touched by grace, bed sheets flying around his naked body, and with the transfixed crowd cheering down below. Seeing him on TV, his former girlfriend, having left him because of his obesity, decides to nurse the man back to life, “because, she said, she sensed in him ‘so much pain and suffering’” (84). Through this unusual mismatch that reminded me of a Carson McCullers love relationship in her short story collection The Ballad of the Sad Café, the two of them do not so much complement (add up) as second (add to) each other, finding a supplément d’âme (solace to the soul) to their human predicament and deep sense of loneliness. The second image functions along a vertical axis, too, but deals with falling instead, bringing to mind Don DeLillo’s novel Falling Man on the aftermaths of 9/11. A female office worker accidentally raises her head from her desk towards the window of her office tower for a fraction of a second and sees the V shape of a woman silently falling down outside, her black hair floating around. These two parallel individual, self-centred lives briefly intersect, yet cannot feel more removed from each other at the same time. Insulated within the illusory safety of the air-conditioned, soundproof building, the office worker “couldn’t hear anything, or make out what was happening. Just point and trajectories” (96). Falling here entails the dissolution of matter into form, and vice-versa, like the raindrops that come falling onto Hsu’s window in the middle of the night in Central Texas, making time liquid.

The third image is from a movie scene in Hitchcock’s film Rear Window, in which a man spies upon a woman from across his apartment unit. The woman is standing by the “open, large rectangular window” (100) of her own apartment, pretending to be having a romantic dinner with her lover, kept hidden from view by a wall, “when, in fact, she’s alone” (101). The man and woman’s eyes never meet, wrapped as they are in their respective solipsistic, Hopperesque solitude. There is often a tension in Hopper’s paintings between the interior and the outside, as there is here, for although exposed to the man’s binoculars and to the film viewer’s gaze, the woman remains oblivious to her surroundings, as if “putting on a show, just for herself” (101). Hsu is a cinephile, and quite a number of his anecdotes are movie reviews of films he remembered watching. Is this because cinema, as a visual art, offers the kind of rear view window and perspectival insight that Hsu, as a diasporic writer, is particularly fond of? Hsu grew up in Yonghe in the northern part of Taiwan before moving to America with his family in the early 90s. Both of his parents have connections through relatives with Mainland China. Hsu recollects his first trip, flying from America, to his father’s home in Pingdu, situated in the northeastern province of Shandong, aged eight. There he learns about the unfathomableness of “ancestral”, family, communal times, meeting with unknown relatives and “generic” (78) Asian old ladies whom he would probably never meet again, yet who are at the same time implacably, absurdly, connected to him by blood. The arbitrariness of diasporic belonging to the transcendental signifier of China is for Hsu further compounded by his father’s complicated relationship with the “Middle Kingdom”, which the latter fled as a child, crossing the Formosa (Taiwan) Strait partly by swimming. For Hsu, China remains, like the middle of the night or the disjointed nature of human relationships, a foreign haunt to which he however keeps returning. His childhood memories of China are in particular associated with his grandmother’s funerals and with the event of having to witness his father’s near-death seizure: “My father later said, that night, he had a dream that my grandmother came to our hotel room, and asked him if he wanted to go on a trip abroad, with her” (80).

To conclude this review, I must admit Hsu’s meta-fictional comments on literary reviews made me rethink the role and function of this “minor” genre. According to Hsu, book reviews often amount to highly subjective and personal scribbling in the margin that is more indicative of the reviewer’s own worldview than it says something about the author, the book being reviewed, or its potential readers. Isn’t it, however, what writing, all writing that is, is about, and what Hsu’s adoption of the essay work form hints at in particular? Hsu argues that writing is altruistic (having in mind the absent reader), while reaffirming the primacy of life over art, which will appeal to carpe diem amateurs and art dilettantes alike. In effect, readers of Middle of the Night should not expect an underlying or overarching theme running through the book, as Hsu does not write for anyone or about anything specifically, his Asian American-ness (and homosexuality) being ultimately of “marginal” concern to him. Hsu is a process artist, that is to say that his primary concern, like the German dance choreographer Pina Bausch or the American photographer David Armstrong, to both of whom he devotes a “time slice”, is “neither of this world, nor of another, neither in the moment that’s past, nor in the one to come, but, in the space and time that is lost, between them” (73). Another scene-image from Hsu’s essay work resonates with me here, that illustrates the supplementary, intra-subjective and partial (ad)equation of re-views (“yourself plus the world minus me” as Hsu puts it), and the way re-views can also, by definition, provide new ways of seeing. An undefined, non-gendered, first person narrator sits in the public transports of a non-situated city, unbeknownst to his/her lover, who coincidently sits two rows in front. Instead of joining him/her, the narrator remains in his/her seat, preferring to watch his/her lover’s back. In doing so, the narrator realises how in their respective, self-immersed anonymity, s/he has never felt so close to connecting with his/her lover: “It occurs to me I had never up until then, seen you. In your completeness. In your solitude. I wonder what you are like without me. Yourself plus the world minus me. It’s a strange feeling, but I feel a lightness and clarity. A bright whiteness shines through me. I can see an outline of myself” (113-4).

PAUL GIFFARD-FORET obtained his PhD in Anglophone postcolonial literatures from Monash University in Australia. He works as a sessional lecturer in English at La Sorbonne University, Paris. He is involved in political activism and a member of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA).

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

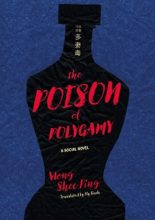

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

The Poison of Polygamy

Wong Shee Ping and translated by Ely Finch

Sydney University Press

ISBN: 9781743326022

Editors’ note: This research essay references Ely Finch’s recently published translation of The Poison of Polygamy (2019). While not a review of the book, the essay offers a point of resonance.

The Poison of Polygamy (Chinese title Duo qi du, shortened as PoP in the following) is a novel published in serial form in the Chinese newspaper The Chinese Times from 5th June 1909 to 10th December 1910. Kuo states that its publication date is between 8 June 1909 and 16 December 1910 (222), but my research indicates the first episode was published on 18 April 1909, and the last on 9 November 1910 (Chinese lunar year). Their corresponding Gregorian calendar dates are 5th June and 10th December. And instead of being published in 52 instalments as mentioned in previous studies (Ommundsen 4), there were actually 53 instalments. There are two episodes with the same number, 25, dated 6 November and 2 December 1909 in the Chinese lunar calendar; the corresponding dates in the Gregorian calendar are 18 December 1909 and 12 January 1910. The author uses an alias, Jiangxia Erlang.

Considered the first novel about Chinese-Australians to be published in a Chinese language newspaper (Huang and Ommundsen 533-544), Duo qi du has gained the attention of critics and translators. Huang and Ommundsen first translated its title from Chinese into English as PoP, and have analysed it from the postcolonial perspective. Kuo has noted the novel’s emphasis on the value of kinship and brotherhood for Chinese immigrants, as well as its criticism of traditional Chinese values and manners. PoP is now being translated by Ely Finch, and the English version will be published by Sydney University Press next year.

The novel is set in China and Australia, beginning between 1850 and 1860, during the Taiping Rebellion, an internal revolt that ran from 1850–64, and which posed a major threat to the Qing dynasty (Dillon 663), and ending between 1880 and 1890. The story is told by an omniscient narrator who interrupts the narrative from time to time, commenting on an event, criticizing a social problem, or initiating a dialogue with the reader. As the title suggests, the novel’s focus is on the harmfulness of polygamy. The central character, Shangkang, is described as having a pointed head like a falcon, indicating his crafty, treacherous character, and foreshadowing the evil he’ll engage in.

At the start of the novel, Shangkang lives in a village of Guangdong and is addicted to opium. He and his wife Ma have been married for three years and are childless. They’re very poor, and when his mother falls ill they’ve no money for a doctor. Ma pawns her clothes and personal possessions to pay for witches and wizards to perform rituals to cure the old lady. When these have no effect, she asks Shangkang to pawn her new padded cotton coat and send for a doctor. However, after taking the formula concocted by the doctor, Shangkang’s mother worsens and dies.

After the burial, life becomes harder for husband and wife. Despite the threat of starvation, Shangkang pawns everything he can get for opium, while Ma forages for wild plants to use as food. One day she stops him from trying to pawn a broken pot; she tells him her cousin has just come back from Australia with a lot of money. Her cousin, she explains, is kind and generous, and she asks Shangkang to seek his help. Shangkang goes and sure enough the cousin, Mr. Ma, gives him money; however Shangkang spends it on opium, leaving little to buy food. He lies to Ma, telling her the money was given him by an old friend. The next day, when Mr. Ma visits, Shangkang’s lie is revealed. Ma tells her cousin it’s difficult for Shangkang to make a living in the village as everybody knows he is dishonest and untrustworthy. Mr. Ma agrees to pay for Shangkang to go to Australia, on the condition he give up smoking opium, and becomes diligent and thrifty. Shangkang agrees, and receives enough money to prepare for his trip and buy food; he asks for, and is given, additional funds to buy medicine to quit smoking. But predictably, Shangkang immediately goes to the opium den.

Mr. Ma arranges Shangkang’s departure, and when the time arrives, Shangkang is ready. Ma is reluctant to let him go, afraid he’ll spend the money on concubines. Shangkang promises he won’t forget her hard work and the hardships they’ve endured. They bid a tearful farewell.

On the voyage, Shangkang experiences seasickness. Fortunately, his co-passenger — whose formal name is Huang Peng, though is better known in the text for his style name, Chengnan — is very kind and nurses Shangkang carefully. Another passenger named Binnan is from the same town as Chengnan. The three men bear the family name Huang, so are referred to as clansmen.

There are over seventy Chinese workers on the ship; it takes seventy six days to reach Australia. When they finally dock, one of them offers to be their guide as he knows the rough direction of the mine where they’ll seek work. They climb mountains and wade across fords, trekking through vast wilderness. They quickly run out of food, and suffer from hunger and thirst. Many die. Some are bitten by venomous insects; and they have to contend with wild animals, heavy rains, lack of shelter, and homesickness.

Resting one day in a wood, they’re attacked by four Aboriginal people. A white hunter named George appears and defends them, though one man is captured and taken away by the ‘savages’ (referred to as Heiman in the text). The men learn they’ve taken the wrong way to the mine, and are now very far from their destination. George leads them to a Chinese farmer nearby who owns a vegetable garden. The gardener, Chen Liang, provides them with sumptuous meals and a place to rest. He helps the men find jobs and settle into the community.

Chen Liang invites the three Huangs to participate in a mining venture. Initially, he is reluctant to cooperate with Shangkang as he finds him wicked and unreliable; but Chengnan refuses to abandon Shangkang due to the bond that’s grown between them. For a time, their venture is prosperous; however a collapse in the mine results in the loss of their profit. They move to another mine and are prosperous again. Once they’ve earned a considerable amount of money, they plan to return home.

During Shangkang’s absence, Ma lives a miserable life of poverty and loneliness. Her mother attempts to persuade her to remarry as there’s been no message from Shangkang who might have died. Ma refuses, saying she would rather die if Shangkang has died, rather than marry another man.

When Shangkang returns to his wife after a separation of six years and sees how her youth and beauty has faded, he despises her. He considers buying a young and beautiful concubine; his indifference to Ma causes her deep pain. Shangkang resumes his opium habit and squanders his earnings, leaving no money for a concubine. They adopt a one year old baby son and name him Jinniu. Chengnan attends the celebration feast in Shangkang’s home and talks with Shangkang about going back to Australia. Shangkang immediately consents.

In Australia, Chengnan’s business prospers and he establishes several stores. He lets Shangkang manage one of his successful furniture manufacturing businesses, and Shangkang thinks again of getting a concubine. He learns that an eighteen year old slave girl named Qiaoxi has come to Australia for an arranged marriage, but refused to marry the man who she thinks is too old and ugly for her. Shangkang comes for a visit and is infatuated at the sight of Qiaoxi. He proposes through her chaperone Ma’am Lian. Qiaoxi agrees, not for his money, but because she believes she can take advantage of his seeming obtuseness and honesty.

After they are married, Qiaoxi meets often with her lover Shuangde while Shangkang works. One day, when the two are having a tryst at home, Ma’am Lian drops by and the two lovers’ adultery is exposed. Shangkang is furious at being cuckolded, but uxorious and entirely under Qiaoxi’s sway, does nothing. Qiaoxi gives birth to two daughters and the four live extravagantly. Chengliang’s business is almost entirely ruined by Shangkang’s neglect. Shangkang and Chengliang return to China. Before they leave, Shangkang asks another clansman Rongguang to run the business, and instructs him to abscond afterwards with the remaining profits.

In China, Qiaoxi asks Shangkang to build a villa away from the neighbours and relatives with the embezzled money. Though Ma is heartbroken to see Shangkang break his promise and dote on Qiaoxi, she succumbs to her fate and to the feudal rules. She is tolerant of Qiaoxi. The latter is jealous, nevertheless, when Ma becomes pregnant and gives birth to a son. Out of malice, she poisons Ma and smothers the baby. When Shangkang learns of the deaths, he grieves and is sorry for Ma and the baby. When he questions Qiaoxi, she grabs him by the throat, strangling him. He dies soon after.

After Shangkang’s death, Qiaoxi becomes more unscrupulous and lives a lecherous life in the villa. One of her lovers is Jing. Jinniu is now twenty and married to a young woman, Li. Jing nearly rapes Li when Jinniu is out one night. Li tells Jinniu, and he avows to avenge her. Qiaoxi overhears this and plots with Jing to kill Jinniu. Their plan fails when Jinniu’s cries for help are heard by nearby villagers; and the townsfolk, as well as people in Jinniu’s old village, decide to aid him by getting rid of Qiaoxi. They finally decide the best way is by lynching, and throwing her into muddy water. They believe the officials who are only interested in accumulating wealth and amenable to bribes, are incapable of carrying out justice. In the end, Qiaoxi is cornered and jumps into a deep pool and is drowned, while Jing and his gangsters are at large.

The novel is eloquently written in classical Chinese. The language is beautiful; the descriptions of the natural world embody and enact the inner life of the characters. The historical and literary allusions are pregnant with meaning. The plot is well-constructed; its social criticism is obvious — and this is related to its genre.

For Western readers and readers unfamiliar with Chinese literary history, PoP might be read as a picaresque novel, but its genre is ‘new fiction’, which has its origins in the magazine New Fiction, established by Liang Qichao in Yokohama of Japan in 1902 (Zhang 86). This genre was made known to the Chinese-Australian literary circle after Liang’s visit to Australia in October 1900 and April 1901 (Kuo 96), followed by the circulation of his New Fiction. During Liang’s visit, the Tung Wah News (former name of the Tung Wah Times) published Liang’s collection of speeches and thoughts, and circulated it widely in the Chinese-Australian community (99). The Tung Wah Times was an agent for Liang’s literary journal New Fiction and shared his opinion of the social value of the novel, and argued that the novel and other new forms of literature had the power to reform society (157). The Chinese Times carried on the reformist ideas of the Tung Wah Times. It sympathized with Chinese revolutionaries and shared their anti-Manchu notions, which is reflected in the novel PoP, consistent with Liang’s ideas.

A prototypal novel of new fiction is Liang’s The Future of New China (1902). Liang was the founder and initiator of this genre; he aimed to improve the old genres, which he felt had failed to help ameliorate social problems. New fiction was to undertake the important task of enlightening the people and promulgating new knowledge and learning (Wang 14). However, what Liang and the other innovators of this genre in Chinese literary history stress, is that new fiction is not the outward form of fiction, but involves a specific method of narration, and specific subject matter. It still preserves the serial or chapter form of traditional novels, and many novels of the new genre still adopt an omniscient narrator, but the narrative pivots around the revelation of social darkness, emphasising social reformation and praising innovation (Xia 11). As PoP does, it venerates the rationality of monogamy, and embodies the progressive ideas of the time. Here ‘chapter’ and ‘serial’ do not mean the same as our understanding of them today. The genre ‘chapter/serial novel’ comes from the story-telling script of the Song and Yuan dynasties. In Chinese serial/chapter novels, the chapter/serial is marked by a number, just as PoP is. ‘Serial’ or ‘chapter’ means ‘scene’, or ‘time’. In Song and Yuan, the stories were told by a story-teller instead of being read, as many common Chinese people were illiterate at that time. The script of a story was too long for the story-tellers to finish in one sitting, so they often ended one fragment with ‘if you want to know what happens afterwards, please listen to me next time’ to attract the attention of the engrossed audience (‘Serial/Chapter’ 10). The length of each scene is nearly the same. Many chapter or serial novels have a title beside each number to summarize the main idea of a chapter, or rather, fragment. According to the contents, new fiction is divided into political fiction, social fiction, and historical fiction. PoP belongs to social fiction, that is, it criticises many social problems prevalent at the time.

Apart from its attack on the evil of polygamy (Serial 1 and Serial 37, the actual serial number of the latter should be 38), Pop is punctuated by the narrator’s criticism of superstition and opium-taking (Serial 1), of charlatanism (unqualified doctors) (Serial 3), the misogynous practice of foot binding (Serial 20) and lack of women’s right to an education (Serial 21). It follows the lead-in of Liang’s The Future of New China on the destructive force of polygamy, in which the narrator tells the tragic story of a man who practices polygamy, is bereaved of his wife and son, and then deprived of his own life — the concubine, in the end, receiving her due punishment. Ommundsen writes that ‘Horrible Poison’, a short story published in the Tung Wah Times, reflects the agenda of the Chinese Empire Reform Association, a movement dedicated to reforming the outdated and corrupt practices of China under Qing Dynasty (Ommundsen 4). In this respect PoP resonates with ‘Horrible Poison’. The editor of the Chinese Times, Chang Luke was a former editor of the Tung Wah Times, and embraced the idea of the newspaper promoting social reform. Early issues covered the reform of education, feminism, and the anti-opium movement (Kuo 84). The Chinese Times shared the Tung Wah Times’s purpose to increase revolutionary and anti-Manchu attitudes (118) The latter shifted from revolutionism to moderate constitutionalism after 1903 (149). The novel bristles with feminist ideas, and criticism of misogynous ideas and practices. At the same time, it is studded with the belittlement of women, the preference for submissive wives, and descriptions of female characters in pejorative terms, which warrants further study.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my supervisor and associate supervisor, Professor Wenche Ommundsen and Anne Collett, who have been very helpful in the proofreading of this paper. Professor Ommundsen has offered advice on its revision. I also appreciate my Chinese supervisor Binzhong Zhu and Zhong Huang, my academic brother, as is called in China, for their help. I also want to express my heartfelt thanks to the librarian staff of UOW for obtaining the microfilm of The Chinese Times for me. and to the editor of this journal, Michelle Cahill, for her patient and careful editing.

Notes

Chinese Times, The. 1909–1910. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria (microfilm).

Dillon, Michael. Encyclopedia of Chinese History. New York, NY: Routledge. 2016.

He, Manzi. ‘Serial/Chapter Novel and the National Style of Narrative Literature (zhanghuixiaoshuo he xushiwenxue de minzufengge)’. Knowledge about Literature and History. 1982(3).

Kuo, Mei-Fen. Making Chinese Australia: Urban Elites, Newspapers and the Formation of Chinese-Australian Identity, 1892–1912. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Press, 2013.

Ommundsen, Wenche. ‘The Literatures of Chinese Australia’. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, 2017. (http://literature.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-150.)

Wang, Zuxian. ‘Diversity of Fictional Genres and Subjects in Foreign Fiction and in Fiction of the Late Qing and Beginning of Republic China (waiguoxiaoshuo yu qingmomingchu xiaoshuo ticai de duoyanghua)’. Academic Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy and Social Science Version). 1993(3).

Xia, Xiaohong. ‘Discriminating the Meaning of ‘New Fiction’ of the late Qing (wanqing ‘xinxiaoshuo’ bianyi)’. Literary Review. 2017(6).

Zhang, Lei. ‘New Fiction and Old Genre: Review of Creative Wring and Translations of New Fiction (xinxiaoshuo yu jiuticai: xinxiaoshuo zhuyi zuopin lun)’. Collection of Modern Chinese Literary Research. 2015(4).

Zhong, Huang and Ommundsen, Wenche. ‘Poison, polygamy and postcolonial politics: The first Chinese Australian novel’. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 2016 Vol. 52, No. 5.

QIUPING LU is a Joint PhD candidate of Wuhan University, China, and University of Wollongong, Australia, Associate professor of Wuhan University of Science and Technology

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

by Tong King Lee

ISBN: 978-90-04-29338-0

Reviewed by A.J. CARRUTHERS

Debates have been raging, in avant-garde studies, over the terms that we might deploy to describe such cultural productions and the longevity of such terms. How do we name unusual literatures in the near present? “Avant-garde” or “neo-avant-garde,” or “avant-garde” and the “contemporary experimental”? Does the historical specificity of the vanguard then preclude usages outside of this, and if so, does “experimental” then sound better historically; the history of experimental literature then to be figured as including many historical moments and contexts rather than stemming from one, what sometimes, and irritatingly gets called the “historic avant-gardes” (as if any other vanguard was not also historic)?

In Brian Reed’s Nobody’s Business: Twenty-First Century Avant-Garde Poetics (2013) we were alerted to the possibility of extending the half-life of the term “avant-garde” in poetics. It brings up enough questions to thoroughly occupy any scholar or layperson starting out in the area, as the Preface states:

Since the 1960s, avant-gardism has a mixed, complex history as a critical concept. Can an authentic avant-garde still exist? Or can there only be shallow effete echoes of past movements and achievements? Can an avant-garde ever actually succeed in bringing about revolutionary social transformation? Does an espousal of vanguardist aims amount to enslaving art to the logic of the marketplace, especially the constant demand for new products and new fashions? Is avant-gardism inherently masculinist? Is it solely a Western phenomenon? The bibliography on such subjects is immense, beginning with Renato Poggioli’s Teoria dell’arte d’avanguardia (1962) and including such landmarks as Peter Bürger’s Theorie der Avantgarde (1974), Andreas Huyssen’s After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (1986), and Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991). One does not have to delve into the footnotes, however, to know that shock and resistance generally characterize the literary establishment’s response to an avant-garde’s emergence. (“Preface” xiii)

I am not interested in further wrangling over terms here, and the various ways that one can navigate this critical history, so much as getting to the works and to the poetics of this book; from this we might see how some of these questions, themselves, might be expanded upon or modified in new light. For that, Tong King Lee in Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics, published in Brill’s Sinica Leidensia series, going since 1931, is an excellent contribution to the field. The argument begins suitably skeptically: “Indeed, it is something of a paradox to speak of defining experimental literature, given that definitions are by their nature institutionalised, and hence to some extent, this runs counter to the spirit of experimentalism” (1).

Two broad elements in Lee’s argument are the materiality of the signifier and technology. How it plays out though will be culturally specific. The roots of these blooms of invention come from the Chinese language which “is often said to be highly visual thanks to the pictographic roots of many of its radicals and characters. On the aspect of sound, innovative poets are able to exploit numerous homophones in Chinese as well as onomatopoeia to create sonic effects that play out the malleable space between signifier and signified” (4). Significant here is that these sonic effects “play out” rather than “play out in” in the malleable space between signifier and signified. There is no sense of an in here, no internal space but rather some outfacing exteriors.

The case studies deal with literature and literary language but also intersect heavily with art practice, and the various ways that art practices have taken up the “semiotic operations” found in other experimental works and across modes (131). Chapter 2 focuses on Machine Translation in Hsia Yü, Chapter 3 on Chen Li, and Chapter 4 on Xu Bing, the well-known conceptual artist. The chapter on Hsia Yü builds off deconstruction, flirting with the notion of the Death of the Translator, an interruptive différance and authorial disavowal to get to HsiaYü’s Pink Noise, a literally transparent book, made of see-through polyurethane leaves, and the intriguing notion of “lettristic noise” (wenzi zaoyin 文字噪音). The emphasis here is on unoriginality, uses of dismantling and permutative means through the digital, and sampling methods. Pink Noise uses Sherlock translation software, and the use of a machine translator “fulfills the poet’s aesthetic expectations of producing irregular poetry by way of its blatantly literal, often unintelligible, and always non-fluent translations” which is to say further that in some bid “to defy the etymological notion of transference in translating (‘translate’ in modern English comes from Latin translatio, ‘carrying over’), the poet textualises the impossibility of ‘carrying across’ any determinate meaning from some perceived source text to some perceived target text by exploiting the openness of language though MT” (34). Google-Translate then allows for back-translation, and a certain degree of grammatical torque and distortion. Lee stresses the embodied and the monstrous here too: Hsia Yü’s use of machine translation intimate with a markedly corporeal poetics. I imagined another comparison with Pink Noise along these lines would be the works of Idris Khan.

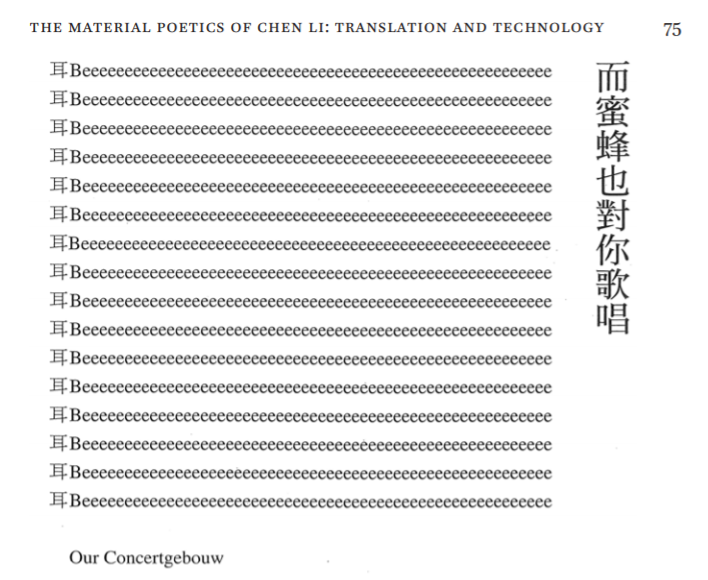

Examining Chen Li’s various works both online and in print, Lee then brings the material elements more closely into focus, putting text to theory around technology and the digital. Chen Li’s poetry embraces concrete poetry, or tuxiang shi 圖像詩 (‘picture-image poetry’), and “visual play on the architectonics of the Chinese character,” elements that fit well with the language: “The pictographic quality of the Chinese script makes it especially amenable to such manipulation” (70). The semiotics of this is compounded and exploded when it comes into the context of bi,- and tri-lingual innovation. Lee offers a reading for the visualist piece “Our Concertgebouw”

Lee brings the materiality of the Chinese signifier in Chen Li precisely to the “technologisation of the word” in way that, in other works like “A War Symphony” show translation to be part of the process of writing itself, not just living in the temporal afterlife of an original. In Lee’s reading of Xu Bing’s language-art works, the complementary Tian-shu 天書 (A Book from the Sky) and Di-shu 地書 (A Book from the Ground), the latter published in an edition from MIT Press, and which is comprised of color-printed emojis that complete a fairly straightforward narrative of one man’s day (somewhat a modernist troping) which I originally read as a novel. As Lee points out, Xu Bing’s purpose is to get beyond the notion of English as a universal language; it is, so to speak, a pre-Babelian vision, one that both harks back to Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian cuneiform and the fate of the written word in digital communication. That is to say, the sheer interactivity that goes on in translation and between modes and text-types is more than a metaphor for intra, or transculturality; these Books seem like, with a dash of art-conceptual irony, real attempts to break through and take a shot at getting beyond translation altogether.

As is of utmost importance to the literary critic, Lee succeeds in bringing the clarity of terms to the specificity of texts. Lee is smart with terms and engages subtle argumentation, outlining the underlying differences between intracultural (within cultural spheres) and transcultural (across or between cultural spheres), and he aptly uses the term intersemioticity which allows us to regard non-verbal signs as “semiotic entities in their own right” (7). I think the term intersemioticity is very wise indeed, when taken back into a properly literary-critical context. Intersemioticity implies also that the seminating influence effects modes and modality. Intersemioticity is especially useful in making sense of Chen Li’s poetics; alongside interlinguality and intermediality. Multimodality is useful in discussing machine translation in Hsia Yü, and we see too in his readings of Xu Bing the value of W.J.T. Mitchell’s work — the imagetext — in normalising and expanding upon the techniques of visual reading, attention to pictoriality and the iconocity of literature.

If it is true that most sizeable literary cultures (or national literatures) have their experimental front lines; inventors, innovators, avant-gardes or neo-avant-gardes, call them what you may, it is also true that not every one of these has a critical industry built around analysing the experimental texts that they produce. Happily, the scholarship and more specifically, literary criticism dedicated to identifying the tendencies of specific avant-gardes and decoding or reading poems outside European and North American contexts, is growing steadily. Over the past ten to fifteen years, comparative studies have shed light on neo-avant-garde practices in transnational, transcultural / intracultural, regional and hemispheric contexts, shifting to explorations of the diasporic avant-gardes and studies of too- much-neglected figures who circulated among the early twentieth-century avant-garde, like Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. One might speculate how the seeming “exhaustion” of current European and American experimental poetics might be reawakened through these interlingual contexts.

Given the context in which this review appears, it is worth adding that developing work on Australian experimental writing might also contribute to this scholarship, widening the reach and regional applicability of such concepts. It is curious that Australian criticism has struggled to find ways of fruitfully speaking about inventive writing, and that no full book has yet been produced on Australian experimental poetics.

I read Experimental Chinese Literature with pleasure and with hope that its sharp critical observations can be of broad use to the contemporaneous flourishing of avant-garde studies, and bring new questions to the field.

A.J. CARRUTHERS is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from Gauss PDF.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people.

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China.

| Reminiscence Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) 碧云天, 黄叶地, 秋色连波, 波上寒烟翠。 山映斜阳天接水, 芳草无情, 更在斜阳外。 黯乡魂, 追旅思。 夜夜除非、 好梦留人睡。 明月楼高休独倚, 酒入愁肠, 化作相思泪。 Nostalgia in Autumn Fan Zhongyan 纷纷坠叶飘香砌, 夜寂静, 寒声碎。 真珠帘卷玉楼空, 天淡银河垂地。 年年今夜, 月华如练, 长是人千里。 愁肠已断无由醉, 酒未到, 先成泪。 残灯明灭枕头欹, 谙尽孤眠滋味。 都来此事, 眉间心上, 无计相回避。 Slow Song Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) 怎一个愁字了得! 寻寻觅觅, 冷冷清清, 凄凄惨惨戚戚。 乍暖还寒时候,最难将息。 三杯两盏淡酒, 怎敌他、晚来风急? 雁过也,正伤心, 却是旧时相识。 满地黄花堆积, 憔悴损,如今有谁堪摘? 守着窗儿, 独自怎生得黑? 梧桐更兼细雨, 到黄昏、点点滴滴。 这次第, | Yellow-leafed earth. On the autumn-tinted river, A green mist floats the waves. Under a sky merging into waters, Hills frame a glorious sunset. The grass stretches endless Into the sun and sky. Home-yearning soul, Travel-weary heart. Dreams, my only refuge Through these endless nights. The moonlit balcony is not for the lonesome traveller. When the wine reaches my sorrow-stricken heart, It turns to tears of longing. Blue clouded sky, Leaves fall on paved steps. In the tranquil night, I hear broken whispers of the cold. Curtains open, I linger alone on the balcony. The Milky Way drapes low across a pale sky. Every year on this night, The moonlight a silk ribbon Stretching thousands of miles. My heart is stricken beyond a drunken cure. Before wine reaches my lips, It had already turned to tears. Watching the lamp flicker as I lean on my pillow, I have long understood the taste of sleeping alone. It hovers between my brows and drifts across my heart, Refusing to be pushed away. Empty solitude, Bleak misery, Despair. I am restless as the warmth makes way for the cold. A few glasses of wine, No defence against the evening wind. Wild geese fly past my heavy heart, My old acquaintances. Petals collect in my garden, Wilted gold. Long past their prime. Standing by the window, I have no courage to face the black night. Tiny raindrops fall among silent trees, Dripping and drizzling into twilight. Everything becomes one word: Sorrow. |

|---|

Translator’s note

I have selected three ci poems from the Song dynasty under a common theme of coping with loneliness. The ci was traditionally a form of song, which later evolved into written poetry with a unique lyrical quality. In order to capture the musical quality of these poems, I used a more liberal approach in my translation and re-created them in a more contemporary style using the English language. My aim was to show the rhythm of language in these poems, which is often lost in traditional literal translations of classical Chinese poetry. I had chosen to de-emphasize the exotic setting of these poems in my translation in order to highlight loneliness as a human condition common across all cultures. In particular, Li’s poem reminded me of English-language confessionalist women poets, and the form and language used in the translation was intended to reflect that similarity.

Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty ci to American confessionalist poetry. Translation has been her passion since childhood, with a special interest in translating poetry from Chinese to English. Her original poems have appeared in Dubnium.

Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty ci to American confessionalist poetry. Translation has been her passion since childhood, with a special interest in translating poetry from Chinese to English. Her original poems have appeared in Dubnium.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Cyril Wong has been called a confessional poet, according to The Oxford Companion to Modern Poetry, based on his ‘anxiety over the fragility of human connection and a relentless self-querying’. He is the Singapore Literature Prize-winning author of poetry collections such as Unmarked Treasure and The Lover’s Inventory. A past recipient of the National Arts Council’s Young Artist Award for Literature, he completed his doctoral degree in English Literature at the National University of Singapore in 2012.

False Labours: Eight Immortals Passing Through

Knuckles on chest, leg under heftier leg:

how we get trapped under and cannot move.

I seem to weigh less every morning.

My tibia is Han Xiangzi’s flute

whittled from golden bamboo

and played with a broken heart; his lover

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.

Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.