December 1, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

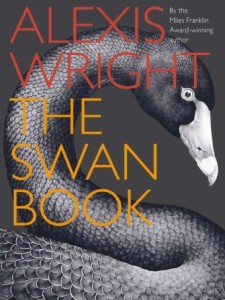

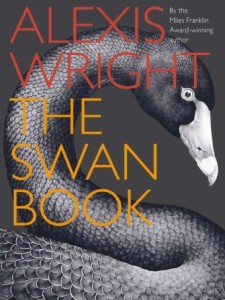

The Swan Book

by Alexis Wright

Giramondo, 2013

ISBN 978-1922146-41-0

Reviewed by MICHELLE CAHILL

The hallmark of a great writer is the capacity to renew and reinvent their creative vision which Alexis Wright achieves with startling virtuosity, sureness, wit and political astuteness in The Swan Book. This is an eclectic fiction, mythopoetic, a meta-narrative epic that takes Wright’s invigorated representations of Indigenous and wilderness mythologies to new levels. Her third novel, it follows on from the internationally-acclaimed Miles Franklin, award-winning Carpentaria, turning its focus to the future, to environmental crises as much as Indigenous crusades. But The Swan Book goes further. It places Wright’s work in a rich, transcultural literary tradition, its verbal pyrotechnics reminiscent of Salman Rushdie’s fiction and James Joyce’s Ulysses; its unflinching forecast written with the potency of Cormac McCarthy or George Orwell, it weaves outback realism with remixed Dreaming, classical references with political allegory, post-colonial and postmodern tropes.

The Swan Book tells the story Oblivia Ethyl(ene), a girl who never speaks after being raped by a gang of petrol-sniffing youths. She is dug out and rescued from the bowels of an ancient story-telling river gum by Bella Donna of the Champions, a European gypsy refugee from climate change wars who arrives on the coast of Australia and makes her way to Swan Lake. The lake has become silted into a swamp, a sand mountain littered with rusted craft, overseen by a white Army. It’s a dystopian future where the policies of intervention remain widespread; where the current wave of conservative thinking is used ‘to control the will, mind and soul of the Aboriginal people.’ The themes of belief, sovereignty of the mind and ancestral voice which were heroically rendered in Carpentaria, find a pessimistic and cleansing register in The Swan Book. Nothing is spared; Wright turns her acerbic lens to illuminate an encompassing scope of Australian political and cultural life, while the land, topography, birds and mutant wildlife flow sinuously in spates and epidemics through the braiding of the narrative. Some passages are written with penetrating zeal:

This was the place where the mind of the nation practised warfare and fought nightly for supremacy, by exercising its power over another people’s land ─the night-world of the multi-nationals, the money-makers and players of big business, the asserters of sovereignty, who governed the strip called Desperado; men with hands glued to the wheel charging through the dust in howling road trains packed with brown cattle with terrified eyes, mobile warehouses, fuel tankers, heavy haulage steel and chrome arsenals named Bulk Haul, Outback, Down Under, Century, The Isa, The Curry, Tanami Lassie, metal workhorses for carrying a mountain of mining equipment and the country’s ore… (165)

There is a sense of the journey of storytelling running through the book, tracing Oblivia’s passage from scribe, whose fingers trace the ghost language of dead trees into Swan maiden, from First Lady wedded to Aboriginal PM, Warren Finch and living in urban sanction to a widow returning to the swamp as guardian of a myth-making swan. Along this winding odyssey through dust storms, floods and cyclones that exist outside of linear time, Oblivia witnesses and internally records the plight of refugees, illegal crossings, the homeless hordes, the aberrant reptiles and displaced birds. One senses that Wright herself gives over to the textual process, surrendering to its detours, its meteorology, absorbing and weaving whatever arises along the way. Her dialectical suppleness and impressive knowledge makes for an innovative, politically-engaged Australian and translocal vision.

The centrality of language is signalled in the remarkable opening prelude, Ignus Fatuus, (meaning ‘illusion’, or ‘phosphorescent light over the swampy ground’) in which the narrator embodies the creative voice as a cut snake virus replicating ideas and firing serological missiles at intruders. It’s a perfect metaphor for the sceptical, chaotically mistrusting tone and establishes voice as an internal harbinger of environmental destruction. Ventriloquisms and shavings of literary allusions combine with popular cultural references ranging from Harry Belafonte’s Banana Boat Song to hybrid motifs such as an ‘Aboriginal tinkerbell fairy.’

Reading the opening chapters I almost felt assaulted by the insistent catalogue of swans: swans of all languages and lyrics are interpolated. The black swan in a Central Australian swamp is an unsettling symbol of Indigenity in its figurative miscegenation with the white swan of Bella Donna’s European folklore. But the brilliance of this excess is to intentionally fetishize the naming and discursive power of language so that the reader experiences language as invasion, as appropriation, as indoctrination, just as Bella Donna herself invades the swamp country of the Northern Territory like ‘an old raggedy Viking’ bringing stories of floating disasters, of refugees from zero geography. After she dies, the swamp people who had once rejected her stories begin to speak Latin in their conversation, becoming ‘Latino Aboriginals’. Wright subversively takes irony and parody to extremes as a way of destabilising not merely language but concepts of nation, deconstructing the colonial currency:

It appeared that the old ghost had colonised the minds of the swamp people so completely with the laws of Latin, it terminated their ability to speak good English anymore, and to teach their children to speak English properly so that the gap could finally be closed between Aboriginal people and Australia. (80)

In making this claim, the hyperbole exceeds stylistic effect and becomes predictive, a potent rehabilitation of colonial assumptions of control. Allusions to the European and White Australian lyric tradition of swans create ambivalence as they parody and place under pressure the authority and superiority of prevailing narratives. Instead, the omnipresent variety of storytelling is eclectic, transcultural and global, invoking inter-racial beliefs of future, past and present. Not only are all kinds of swans admitted into the way that stories are told, the characters are genetically diverse, or like Warren Finch’s minders, ‘inter-racially bred’. Half Life, the mild-mannered camel man who guides Oblivia during her Ghost walk tells her:

We are Aboriginal herds-people with bloodlines in us from all over the world, he added, and dreamily listed all the world’s continents that he could remember being related to these days, Arabian, African, Asian, Indian, European all sorts, pure Pacific Islander ─ anywhere else I didn’t mention? Well! That as well! Wherever! Even if I haven’t heard of it! No matter ─ we got em right here inside my blood. I am thick with the spirits from all over the world that I know nothing about. (315)

Wright’s work is reconstructive, seeking to operate outside of colonial paradigms and boundaries, refusing to be contained. She is able to seamlessly shift gears from third person narrator to interior monologue, from Warren to Oblivia’s point of view. Sections of the novel that contain more conventional dramatic prose such as those that describe Warren Finch meeting with the Aboriginal caucus are skilfully juxtaposed to provide relief from denser periphrastic prose. A descendent of the Waanyi people, Wright’s vast experience of activism, of policy-making bureaucrats and small-town, outback corruption is evidenced. One could argue that the meta-fictional structure of the novel feels somewhat contrived with a prologue and an epilogue used to frame a less self-conscious tension between the polyphonic narrator and the narration however the unevenness is intentional; Wright asserts herself as a highly skilful, erudite yet relaxed storyteller, warping the conventions to compromise aesthetic purity for the benefit of interrogation. The humour is eclectic, switching wavelengths and vernaculars arbitrarily so that languages and styles are remixed and mashed up.

Aside from its sheer literary brilliance, I find the strengths of this novel to be its refusal to seek order or resolution and the way it replicates so much diversity: indeed, as the narrator suggests, ‘How bold to mix the Dreamings.’ In her essay “On Writing Carpentaria” Wright speaks of memory and trauma, asserting that

When faced with too much bad reality, the mind will try to survive by creating alternative narra-tives and places to visit from time to time, or live in, or believe in, if given the space. Carpentaria imagines the cultural mind as sovereign and in control, while freely navigating through the known country of colonialism to explore the possibilities of other worlds. (1)

In The Swan Book she writes a mythopoesis of swan ghosting, of environmental havoc and (un) heroic Indigenity where the sovereign mind and colonial repression are in schism. If there is a swan song it is madness, but the many registers of Oblivia’s silence reinscribe themselves as a timeless Dreaming. This is a self-reflexive book, refusing paternalistic narrative conventions endemic to our literature. Wright compels us to read actively; to reconsider the violence that brutalises Aboriginal Australia and to deconstruct the assumptions and complacencies which fabricate our ideals of nature and nation.

NOTES

1. Wright, Alexis “On Writing Carpentaria” HEAT, 2007

MICHELLE CAHILL writes poetry and fiction. Her reviews and essays have appeared in Southerly, Westerly, Jacket, Poetry International Web and forthcoming in Wasafiri. She was the CAL/UOW Fellow at Kingston University. With Boey Kim Cheng and Adam Aitken she co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets.

November 26, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Christopher Pollnitz’s Little Eagle and Other Poems was a Wagtail publication in 2010, and his six “American Idylls” were in Mascara 11. He has written criticism of Judith Wright, Les Murray, Alan Wearne and John Scott, as well as D. H. Lawrence, and been a reviewer for Notes and Queries and Scripsi, as well as The Australian and Sydney Morning Herald. His edition of The Poems for the Cambridge University Press series of Lawrence’s Works appeared in 2013.

Christopher Pollnitz’s Little Eagle and Other Poems was a Wagtail publication in 2010, and his six “American Idylls” were in Mascara 11. He has written criticism of Judith Wright, Les Murray, Alan Wearne and John Scott, as well as D. H. Lawrence, and been a reviewer for Notes and Queries and Scripsi, as well as The Australian and Sydney Morning Herald. His edition of The Poems for the Cambridge University Press series of Lawrence’s Works appeared in 2013.

Satin bower bird

He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not

watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter . . .

Sartre

Black Prince of the undergrowth, to me his crackle

and hiss seem off-station, but you and he have a

thing together. As I finish each two litres

of juice, you put the lids out in the garden

and your pretty boy comes again and again carrying

awkwardly off in his beak the royal blue baubles.

So intense, so intellectual. I see him sitting

at a sidewalk café, trading Gitanes and banter

with Jean-Paul and Albert, him in lustrous leather

while Simone looks on askance from another table

or eavesdrops for news of post-existentialism

and clues on how to pick up. Smoke and mirrors . . .

It doesn’t do it for him, the bum-fuss and fluster

of hens flouncing in their pastels. Deep in his bower

blue-lit from below, magnified by his comb, I imagine

him preening, and know who it is he preens for

—him with his satin cloak and his rod of amber

his necromancy and his dark effulgence.

Subterranean cool that burns out—is this what maleness

amounts to? Brilliant fencer, prince, philosopher

or Freddie Mercury? Noting the uncollected

lids, you say He’s moved on, disappointed

but not surprised. You’ve other things to get on with

while I rack my brains conjuring up some witticism.

Kookaburra

Quem deus vult perdere, dementat prius.

Anon.

Whom the gods would destroy, they say, but isn’t it rather

since the gods are mad, their devotees drive them crazy?

That one at the barbecue, proper clever feller

left the bread roll in your hand, still with the sauce on

and stole the fire for his people, as well as the sausage.

And now this one, time and again dive-bombing

in the kitchen window his own adolescent image

—demented. We worry about him and the damage.

We tape up tabloids over the glass to distract him

but still he comes, kamikaze seeking his crystal.

One day it’s different, he approaches his rival close-up,

childish anger morphing to inquisitiveness.

You tell me I should speak to him more nicely

but my every word is laced with the mordant satire

reserved for watchers of reality television

or addicts of cooking shows who are just as stupid.

“Look here,” I say, making a chicken sandwich.

“This bird came in yesterday. His name was Hansel.”

Unperturbed he inspects the preparation bench and oven

—he doesn’t tweet but his eyes are bright with banter.

He peers in like Satan at this weird domestic Eden

little realising in his innocence what he’s seeing.

But hang on, if he’s innocent I’m the serpent

long, lithe and upright to his stocky Adam

and remembering how a kookaburra tackles

a six-foot common brown (a good yard dangling

each side of the beak, snake head a bloody tulip)

that gaze could terrify. No, no, forget it

—he’s a creepy bird, but he’s a bird for all that.

Comes another day, another stage of intimacy

—beak to the pane, and perched on the ledge of the window.

When I move towards him, he cranes even closer

when I step away, he edges back. Is he seeing

me in himself, outlined in his own reflection

Or is he seeing the greater Self ascending

to Nothingness with the ghostly Kooka Spirit?

I put the knife down, I fidget about the glasshouse

of my insecurities, my every move filled with

self-consciousness and loathing. I can’t bear his devotion,

he gives me the creeps, he gives me the creeps absolutely.

On the third day, you blow him a kiss through the window.

He pecks the pane and is off, to join the bush chorus.

He’s growing up perhaps, losing his religion.

White-bellied sea eagle

of ryal egle myghte I telle the tale,

That with his sharpe lok perseth the sunne,

And ys the tiraunt of the foules smale.

Chaucer

The Little Wobby eagle in my father’s death year

I remember like an incandescence burning

to burst from casuarina darkness, trawl the river

then flip back, and up again, with a wasp-like talon.

Had I been another Christopher I might have adopted

that estuarial Hawkesbury bird for symbol,

although, in hindsight, I’d rather take the little

smouldering wicks of the she-oak for my image

for there’s another candle that can light me:

us in the car park, the great swoop of coastline southwards;

their beaks like butcher’s hooks, gannet after gannet

mindlessly crashing into the cup of sorrows

that suddenly empties, as the eagle pulse-glide-pulses

overhead of all; and you in the car repeating

details of your friend’s cancer prognosis. All I could think of

was getting away overseas on leave and a conference;

and you—would she still be here on our homecoming?

Reviewing, Promethean eagle, your outstretched scalpel

drawn over the grey breasts and belly of the waters

I don’t yield much to my fear of you, nor do I take much

heart from your liverish victim. Given pharmacological

aid I can dispense with a demigod’s foreknowledge

(or doctor’s) of what I can endure for what duration.

Now it’s dementia I fear, particular losses

of others, and having no busy mind to distract me.

November 26, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Benjamin Dodds is a Sydney-based poet whose work appears in a variety of journals and magazines. Two fun factoids: (1) Benjamin collects Mickey Mouse watches, and (2) his first collection, Regulator, will be published by Puncher & Wattmann in early 2014.

Benjamin Dodds is a Sydney-based poet whose work appears in a variety of journals and magazines. Two fun factoids: (1) Benjamin collects Mickey Mouse watches, and (2) his first collection, Regulator, will be published by Puncher & Wattmann in early 2014.

Unsheathed

Split up the back like dirty

slips, the ghostly cases

stand unmoving in the heat.

They mark the places from which

these prawn-eyed death-rattlers

have lifted themselves

on broad leadlight blades into

summer’s ripening dryness.

A far-off version of

me holds one up close,

Yorick-style.

The alien skin balances on

up-turned palm, primed

to catch even the slightest breath of breeze.

It’s hard not to wonder

just how it might feel to peel oneself

from within a congealing shroud,

to leave a pair of crystal domes

where obsidian eyes

once nested

unblinking.

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Liang Yujing writes in both English and Chinese, and is now a lecturer, in China, at Hunan University of Commerce. His publications include Willow Springs, Wasafiri, Epiphany, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review, Bellevue Literary Review, and many others.

Liang Yujing writes in both English and Chinese, and is now a lecturer, in China, at Hunan University of Commerce. His publications include Willow Springs, Wasafiri, Epiphany, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review, Bellevue Literary Review, and many others.

Zuo You is a Chinese poet based in Xi’an. His poems have appeared in some major literary magazines in China. He is hearing-impaired and can only speak a few simple words.

Zuo You is a Chinese poet based in Xi’an. His poems have appeared in some major literary magazines in China. He is hearing-impaired and can only speak a few simple words.

The Hotel

Celestial trees stand upside down outside the window. The train a crackless gap

falling down from the clouds. Tonight I stay with bats,

crooning for darkness. Rocks contract their four fingers.

The wall gradually resembles the face of my grandma who died a decade ago.

Empty bells mingle with streetlight. Under the moon,

the tea is fragrant. A woman guest stays in the adjoining room, playing the flute.

One of her oil-copper breasts lies outside the quilt. Laden with grief,

she plays a series of vacant echoes.

Whose cat suddenly jumps on the table? A teacup rolls. It keeps up its courage:

tiptoed, it creeps into the hot edge of the woman guest’s quilt.

旅馆

左右

窗外倒立着天空的树。火车像云朵上掉下来的

没有裂痕的缺口。今夜我和蝙蝠们在一起

为黑暗低歌。岩石紧缩着四个手指头

墙面越来越和逝去十年的老祖母——脸庞吻合

空荡荡的钟,和路灯交杂在一起。月光下

茶香喷喷。吹笛的女旅客,住在我左手隔壁

她一只油铜色的乳房,掉在被外。忧伤满面

吹出空荡荡的回声

谁家的猫突然窜在桌面上,茶杯翻滚。它一直在鼓足勇气:

轻手轻脚,溜进女旅客滚烫的被角

Horary Chart

Cold night falls. It keeps raining. The air is fresh.

Inside me, a horary chart is turning without stop. Petals clinging to the ground.

A conscious wind gently knocks at my door. The sandglass on my lips has foretold:

my dream will go back to where you are lost.

桃花上的卦盘

寒夜来临。雨一直下着,带有清新的空气

身体里的卦盘旋转个不停,花瓣沾在地角

风随意识轻轻敲门。唇上的沙漏预告过我:

在哪里遗失过你,我就梦回哪里

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Zeina Issa is a Sydney based interpreter and translator, a columnist for El-Telegraph Arabic newspaper and a poet.

Zeina Issa is a Sydney based interpreter and translator, a columnist for El-Telegraph Arabic newspaper and a poet.

Khalid Kaki was born in Karkouk, Iraq. He moved to Madrid, Spain and has resided there since 1996. He is a poet, writer, artist and musician. He won the Grand Prize of Poetry at the International Poetry Nights at Curtea de Arges, Romania in 2012. He has published three poetry collections.

A belated message from “Halabja”

The children, the mules

and the dragonflies

fell asleep exhausted

in the shade of the village’s clay walls,

they will not wake up again…

Nor will the sunflowers

bowing their heads after the last sunset…

* * *

The women villagers

the harvesters of wheat,

the carriers of water from the spring,

the milkers of the morning’s first drop…

They shall stop

at this border in life,

despite the faithful sun

promising them much more

* * *

The singing voice of the pupils

spreading across the mountain’s map,

hurried towards the ringing bell of death

thinking it was time for class…

* * *

The sticky white clouds

did not distinguish the snakes from the sparrows,

nor the gates from the tiny windows…

They travelled through the houses and the alleys

and devoured the swallows’ nests,the village’s lamps,

its rocks and its fruits…

And they stretched, bleating inside the stables

like an animal spattering its poison and flames

* * *

Cadavers embraced

grabbing each other in fear…

The four cardinal points

were leading to the same direction…

They died on their land

it was the only direction

* * *

The deformed birds made of steel

dropped their weighty gifts on them…

Coated by wrappers of pain

they returned to eternity

* * *

The dreams, the shoes and the horseshoes

melted in the crucible of this little hell…

Death was a mobile well

drenched in captured lives.

رسالة متأخِّرة من “حلبجة”

الأطفال والبِـغال

واليـعاسـب

التي رقدت منهكـةً

في ظل الـجدران الطـيـنـيّـة في القريـة ،

لن يـستـيـقظـوا بـعد الآن ..

كذلك أزهار الشـمـس

التي أطرقَـت بعد الغروب الأخير..

* * *

نساء القريـة

حاصدات السنابل،

حاملات الـماء من الـنَـبع،

حالبـات ضرع الصـباح ..

سـيَـتَـوَقَّـفـنَ

عند هذا الـحد من الـحياة،

رغـم إن الشمسَ الـمخـلِصة

وعَـدَتـهُم بالـمَـزيـد

* * *

نَـشـيد التلامـيذ الـمُنتشرين

على خارطـة الـجبل،

لـحـقَ راكضاً بـجرس الـموت

ظانّـاً أنـّهُ الدرس ..

* * *

السُحُب البِـيـض الـلَّـزجـة

لـم تـميـِّز الأفاعي مِن العصافـيـر،

ولا الأبواب مِن الكـوى ..

سارَت في الـمساكن والشِعاب

والتهمت أعشاش السـنونـو،

وفوانـيـس القـريـة

وأحـجارها والـثِـمار ..

وتَـمـَطـَّت وثَـغـَتْ في الإسطـبـلات

كـحيوانٍ من نِـثـار الـسُم والنـار

* * *

تعانـقت الـجُـثَـث

تـتخـاطَفُ فـزعاً ..

إلـى بعضها كانَـت

تؤدي الـجهات الأربـع ..

ماتوا في أرضهم

التي كانت الـجهة الوحيدة

* * *

الطيور الـحديدية الشـوهاء

ألـقـت علـيـهم

هدايـاهـا الـثـقـيـلـة ..

مغمورين بالألـم الـمغـلَّف

عـادوا إلى الأبـد

* * *

الأحلام والأحـذيـة والـحدوات

ذابت في بوتـقة الجحيم الصغيـر..

كـان الـموت بـئـراً متحـركـة

تـنـضَحُ بأقـفال العُمرِ الكبـيـرة

He went and came back

He went to the orchard

and came back with a flower…

To the shops

and came back with bread

and a can of sardines..

To the war

and came back with a thick beard

and letters from the dead!

ذهبَ وعادَ

ذَهب إلى البستان

فعاد بزهرة..

وإلى السوق

وعاد بخبز

وعلبة سردين..

وإلى الحرب

فعاد بلحية كـثـة

ورسائل من موتى !

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Jan Owen’s most recent book is Poems 1980 – 2008. Her selection of Baudelaire translations has been accepted for publication in the U.K., and a New and Selected, The Offhand Angel, is also forthcoming in the UK with Eyewear Publishing.

Jan Owen’s most recent book is Poems 1980 – 2008. Her selection of Baudelaire translations has been accepted for publication in the U.K., and a New and Selected, The Offhand Angel, is also forthcoming in the UK with Eyewear Publishing.

La mort des amants

Nous aurons des lits pleins d’odeurs légères,

Des divans profonds comme des tombeaux,

Et d’étranges fleurs sur des étagères,

Ecloses pour nous sous des cieux plus beaux.

Usant à l’envi leurs chaleurs dernières,

Nos deux coeurs seront deux vastes flambeaux,

Qui réfléchiront leurs doubles lumières

Dans nos deux esprits, ces miroirs jumeaux.

Un soir fait de rose et de bleu mystique,

Nous échangerons un éclair unique,

Comme un long sanglot, tout chargé d’adieux;

Et plus tard un Ange, entr’ouvrant les portes,

Viendra ranimer, fidèle et joyeux,

Les miroirs ternis et les flammes mortes.

The Death of Lovers

We shall have beds imbued with faint perfumes,

and flowers from sunny lands on shelves above

the sofas deep and welcoming as tombs

will bloom for us as sweetly as our love.

Flaring up, our hearts will shine through space

like blazing torches spending life’s last heat,

with our twin souls, two mirrors face to face,

reflecting back their dazzling doubled light.

One evening born of rose and mystic blue,

a lightning flash will leap between us two

like a long sob heavy with last goodbyes;

and later on, half-opening the doors,

an angel slipping in with joyful eyes

will raise the tarnished mirrors and dead fires.

La mort des artistes

Combien faut-il de fois secouer mes grelots

Et baiser ton front bas, morne caricature?

Pour piquer dans le but, de mystique nature,

Combien, ô mon carquois, perdre de javelots?

Nous userons notre âme en de subtils complots,

Et nous démolirons mainte lourde armature,

Avant de contempler la grande Créature

Dont l’infernal désir nous remplit de sanglots!

Il en est qui jamais n’ont connu leur Idole,

Et ces sculpteurs damnés et marqués d’un affront,

Qui vont se martelant la poitrine et le front,

N’ont qu’un espoir, étrange et sombre Capitole!

C’est que la Mort, planant comme un soleil nouveau,

Fera s’épanouir les fleurs de leur cerveau!

The Death of Artists

How often must I shake my jester’s stick

and kiss this dismal caricature? Will I ever

hit the hidden target? Tell me, quiver,

how many more lost arrows will it take?

We waste our souls in subtleties, we tire

of smashing armatures to start again

in hopes we’ll stare the mighty creature down

that we’ve sobbed over with such hellish desire.

Some have never ever known their god,

and these failed sculptors branded with disgrace

go hammering their chest and head and face,

with one last hope, a capitol of dread—

that death sweep over like a second sun

and bring to bloom the flowers of their brain.

La Cloche fêlée

Il est amer et doux, pendant les nuits d’hiver,

D’écouter, près du feu qui palpite et qui fume,

Les souvenirs lointains lentement s’élever

Au bruit des carillons qui chantent dans la brume,

Bienheureuse la cloche au gosier vigoureux

Qui, malgré sa vieillesse, alerte et bien portante,

Jette fidèlement son cri religieux,

Ainsi qu’un vieux soldat qui veille sous la tente!

Moi, mon âme est fêlée, et lorsqu’en ses ennuis

Elle veut de ses chants peupler l’air froid des nuits,

Il arrive souvent que sa voix affaiblie

Semble le râle épais d’un blessé qu’on oublie

Au bord d’un lac de sang, sous un grand tas de morts,

Et qui meurt, sans bouger, dans d’immenses efforts.

The Cracked Bell

How bitter-sweet it is on winter nights

listening by the fire’s flicker and hiss

to distant memories slowly taking flight

with the carillons resounding through the mist.

Faithfully the sturdy-throated bell

flings its holy cry abroad. Unspent

despite it’s years, it’s vigorous and well

—a veteran keeping watch inside his tent.

As for me, my soul’s cracked through with pain;

I scarcely hold a tune in sun or rain,

and often now my voice turns weak and thin

as the last rattling breaths of a wounded man

crushed under a mound of corpses piled up high

next to a lake of blood. Struggling to die.

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Tony Birch is the author of Shadowboxing (2006), Father’s Day (2009) and Blood (2011), shortlisted for the 2012 Miles Franklin Literary Award. His new collection of short stories, The Promise, will be released in 2014. Tony teaches in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne.

Father Divine

Walking home after the paper round one Saturday morning Sonny and me come around the corner and saw a furniture van parked in the street. Workers were unloading cupboards and tea chests from the truck and carrying them into the house next door to Sonny’s place. It had been empty for months and the landlord had cleaned it out, painted it up and fixed the roof on the old stable at the back of the house. The stable had been used as a carpenter’s workshop from a long time back, but had been padlocked all the time I lived on the street.

We stopped on the footpath and watched the removalists wrestle with a piano, standing on its end and strapped to a trolley. The workmen were sweating and swearing at the piano like it was some fella they might be fighting in the pub.

‘Fucken iron frame,’ one of them grunted to the other. ‘I hate iron frames. I’m marking up the job for this. Fuck it. Double time for the day.’

They stopped for a smoke. One of them looked over at us, leaning against Sonny’s front fence eyeing them.

‘What you two looking at?’ he bit at us. ‘Can you carry this cunt on your back? If you can’t, stop gawking and let us get on with the job.’

It was our street they we on, so we weren’t about to fuck off any place. I pinched Sonny on the arm and nodded. We shifted to the front of my place and sat on the front step.

‘You reckon he’s happy with his job?’ Sonny laughed.

‘Wouldn’t you be? No weight in that piano there. Your pushbike’s heavier. He’s piss-weak, I reckon.’

They finished their smoke and dragged the piano into the house.

‘My mum can play the piano,’ Sonny said.

It was the first time Sonny had spoken about his mother since she’d shot through on the family with some fella she worked with at the tyre factory some time last year.

‘You don’t have one in your place. Where’s she play?’

‘Before we came here. We lived with my auntie, mum’s older sister, for a time. They had a piano in the front room. Mum would play and we’d all sing.’

‘What songs did she play?’

He looked away from me, along the street, to the furniture van.

‘Just stuff. I forget.’

The men came out of the house and stood at the back of the truck. The one who’d abused us was scratching his head and looking over. He buried his hands in his pockets and walked toward us.

‘You two want to make a couple of dollars?’ he asked.

‘You just told us to fuck off,’ Sonny called back.

‘I was just pissing around.’ He held out his hand. ‘Jack.’

I shook his hand and Sonny followed.

‘We got a load of folding chairs in the back there, maybe fifty, sixty, and my mate, Henry, and me want to get away for lunch and a beer at the pub. You two want to give us a hand for a couple of dollars?’

‘What’s a couple add up to?’ Sonny asked.

‘What it’s always been. Two dollars.’

Sonny held up three fingers.

‘Two’s not enough. It’s a Saturday, so we’re on time and a half.’

‘Jesus, you a union organiser or something? Fuck me. Three dollars then. Let’s get cracking.’

The chairs were made of wood and weighed a ton. I grabbed one under each arm and followed the removalists through the house. It smelled of fresh paint. We crossed the yard and walked through the open double doors of the stable. The piano was sitting at one end of the room, next to a brass cross, stuck on the end of a long pole. Picture frames rested against a wall. They looked like the prayer cards the Salvos gave out on street corners, only a lot bigger. I read one prayer aloud.

There Can Be No Being before God, As God Has No Mother.

‘Amen,’ Sonny laughed, making the sign of the cross over his heart.

One of the picture frames was covered in a piece of green cloth. Sonny pulled it away from the frame. We stared at a painting of a man in a dark three-piece suit and tie. He had shining black skin, dark eyes and was posing in a big velvet chair. Kneeling next to him was a young woman with golden curls, flowers in her hair, and white, white skin. She was looking up at the black man and holding his hand. Across the bottom of the painting were the words Father Jealous Divine & Mother Purity Divine.

‘Fucken weird,’ Sonny said.

‘Yep. Weird.’

Jack, the removalist, called his mate over.

‘Henry, take a look at these two.’

Henry was stacking chairs against the far wall. He shuffled over, scratching the arse of his work pants. He stood next to me and crossed his arms and studied the painting.

‘She’s not bad looking, Jack.’

‘Look at the way that old blackfella’s into her with those eyes. Bet he’s fucking the pants off her.’

‘Fucking the pants off her,’ Henry agreed. ‘What do you reckon, boys? He fucking her or what?’

The black man looked old enough to be her pop, although he couldn’t be, I guess, seeing as he was black and she was white. Henry repeated the question to Sonny, who like me, was too embarrassed to answer.

I heard heavy footsteps behind me in the yard.

A tall thin man stood in the doorway of the stable. He was wearing a dark suit, white shirt and string tie. His silver-grey hair was cut short, and even from the distance of the other side of the room I could see his cold blue eyes burning a hole in Henry’s heart, who was rubbing his chest with his hand and showing pain in his face.

The man stepped into the stable, walked toward Henry and stopped maybe six inches from his face. He looked down at the ground, at his own shining black leather shoes and back up at Henry, who turned away, too afraid to look the man in the eye.

‘Your remark?’ the man asked, raising an eyebrow.

Henry licked his bottom lip with his tongue, trying to get it moving.

‘That wasn’t any remark,’ Jack interrupted. ‘We were just mucking about with the boys.’

The man turned and set his eyes on Jack, making him feel just as jumpy and uncomfortable.

‘Do you often speak on behalf of your co-worker?’

‘Like I said, we were just mucking about.’

No one moved. The man took a white handkerchief out of his coat pocket and dabbed his mouth. He looked around the room.

‘Please set the chairs in even rows, an equal number of chairs, separated by a clear aisle. And move the piano to right side of the room. Would you be able to hang the framed psalms? And,’ he looked down at the green cloth that Sonny had pulled away from the painting pointed to the end wall and said, ‘mount the portrait of the Messenger and Mother Divine in line with the aisle. Are you able to do that?’

‘The Messenger,’ Jack smiled. ‘Sure. We can look after him, can’t we, Henry? It ‘ll cost a little more … Mr Beck, weren’t it?’

‘Reverend Beck.’

Jack offered his hand. The Reverend ignored it. He wiped his hands clean with the handkerchief and put it back in his pocket. He took a small bible from his pocket and held it in his hand. His eyes flicked to the side, sharp as a bird spotting a worm. A girl had arrived at the stable door. She was around my age and wore a long plain dress, almost her ankles, and a scarf on her head covering most of her fair hair. Even in her costume I could see she wasn’t bad looking. The Reverend turned to face her. She blinked and bit her lip.

‘Selina?’ he asked, stone-faced.

She spoke with her hands held together in prayer.

‘Some of the followers are here, asking what work you need them to do.’

The Reverend opened his arms, raised his hands in the air and closed his eyes. And he smiled.

‘There is work for them to do here. In our church.’

He stared up at the roof. While Jack and Henry were looking at him like he was some circus freak Sonny and me slipped out of the stable, into the yard and jumped the side fence into his place.

‘Fucken lunatic,’ I panted. ‘Did you see his eyes?’

‘Seen them, but not for long. I was too afraid to look at them. And what about the picture of the old black boy?’

‘Yeah. Did you see the girl who come into the stable? She looked pretty, under that scarf.’

‘Your off your head. I bet she’s crazy too.’

‘Still not bad looking.’

‘And crazy. You hear what he said. A church? Must be against the law, putting a church in a back shed?’

‘Maybe. But then so is running a sly-grog. Or an SP. And the two-up. Police can’t close any of them down. Hardly gonna go after a nutcase running a church.’

Lots of people came and went from the house. Men in dark suits and women and their daughters in the same long dresses and head scarves that Selina went around in, although she didn’t go around that often. I never saw her in the street on her own, and if she went to any school it wasn’t to mine. I sometimes spotted her sweeping the front yard with a straw broom or sitting up on the balcony with a book. I made noises when I walked by the house to get her attention, but she never looked my way, not even from the corner of her eye as far as I could tell.

I was woken early one Sunday morning by banging in the street. I crept downstairs, so not to wake my old man, who’d got home in the middle of the night from a road trip, and opened the front door. It was cold out. The street was crowded with cars and people were pouring into the Reverend Beck’s place. I went back into the house, made myself a cup of tea and took it up to bed. I could hear the piano playing in the stable, followed by some singing of hymns and shouting and screaming out.

Sonny knocked at my window a few minutes later and let himself. He had sleep in his eyes, his hair was standing on end like he’d stuck his finger in the toaster and he was wearing the jeans and jacket he’d had on the night before. They were dirty and crumpled. He must have slept in them.

‘You look like a dero, Sonny.’

‘Fuck up. You’re no day at the beach yourself.’

He picked up my mug of tea and took a long drink.

‘You hear that racket going on next door?’

‘Yeah. It woke me.’

‘We should go take a look.’

‘It’s freezing out.’

‘Put a jumper on. Come on.’

‘Not me. I’m staying in bed.’

He finished off my tea.

‘Please yourself. Your girlfriend, that Selina will be there.’

He was halfway out the window when I called him back.

‘Wait. I’ll come. And next time don’t drink all my tea.’

I followed Sonny out the window onto his roof and down the drainpipe. A thundering tune was almost lifting the roof off the stable. Sonny unlocked his back gate and we crept along the lane. He put an eye to a crack in the stable door. I kneeled beside him and tried pushing him along so I could take a look. He wouldn’t budge and was muttering ‘fuck, fuck,’ over and over to himself.

‘Move, will ya?’ I hissed, ‘and let me take a look’.

He pointed to a knothole close to the bottom corner of the door. I lay down on my guts. The ground was muddy and I was soaked through in about two seconds. I put my eye to the hole. All I could see were hundreds of chair legs and the ankles of old women and young girls, escaping the hems of long dresses. I noticed one ankle, bone white. I reckoned it might belong to Selina. I followed it upward, tapping along with the hymn. I wanted to reach out and touch that ankle and slide one hand up its leg and the other down the front of my pants.

The singing ended and it went quiet, except for my heartbeat and Sonny breathing. When the Reverend’s voice boomed out across the stable, Sonny jumped and stood on my hand. I bit on a lump of dirt to stop myself from crying out in pain. The words the Reverend was preaching didn’t make a lot of sense.

‘… And we have been brought to this Holy Place at the call of the Messenger … God Himself, Our Father Divine has called us here from across the ocean … and Mother Divine, in her chaste beauty and purity calls us to abstain in this place, this House of Worship …’

‘You hear that, Sonny?’ I whispered.

He nodded his head and stuck his ear against the crack in the door.

‘… And was it not proven in the days prior to the Great Earthquake of 1906, that the Messenger attended the city of San Francisco, a site of pestilence and evil, at the behest of the Holy Spirit, and bought wrath upon the sinful … And do we not know that when the Messenger was imprisoned for His works his gaolers were struck down by lightning and He was able to free Himself …’

The more he went on with the Bible talk, the louder and deeper his voice got. Women in the audience started crying and the men called out in agreement. The Reverend stopped preaching and people in the room stood up and clapped and cried out. The piano struck up another tune and they sang some more. Sonny tapped me on the shoulder and called me back along the laneway, into his yard.

‘You ever hear stuff like that?’ I asked. ‘And all them women babbling? Gave me the frights.’

‘Look at you,’ he laughed. ‘You’ve been rolling in crap.’

The front of my jumper and the knees of my jeans were covered in a mess of mud and dog shit. I tried wiping it off, but all I did was move it around.

‘My mum ‘ll kill me.’

Sonny couldn’t stop laughing.

‘And after that your old man will kill you double.’

I scraped a handful of the mess from my jumper and flung it at him, whacking him on the side of the face.

‘Don’t think its funny, Sonny. She’s gonna flog me for doing this.’

‘Stop worrying. Come inside and I’ll throw the stuff in the twin-tub and dry it by the heater.’

We sat in Sonny’s kitchen, me wearing a pink frilly dressing gown that belonged to his mum, while my clothes went through the machine.

‘You got any toast, Sonny?’

‘I don’t have any bread.’

‘No bread? What about a biscuit?’

‘Don’t have any. There’s nothing left in the house,’ he said, jumping from his chair and tugging at the sleeve of his jumper.

‘Where’s your old man? In bed with a hangover?’

He sat back at the table and looked down at his hands

‘He’s not here. Haven’t seen him for two days.’

It made sense all of a sudden, why he looked like shit and why there was no food in the house.

‘Where’d he go? What have you been living on? Nothing I bet.’

‘Shut up with the questions, Ray. I can take care of myself. You want to play copper, get yourself a badge.’

‘I was just asking …’

‘Don’t ask. Or you can give back my mum’s pink gown and piss of home in the nude.’

With my father off the road we had roast for Sunday lunch. He never talked much while he was eating, but my mother loved a chat. Said that the table was the place for the family to come together.

‘Why’d you head off early this morning?’ she asked.

‘No reason.’

‘Come on, Ray. You’re never out of bed early on a Sunday unless you’re off with your mate Sonny somewhere you’re not supposed to be.’ ‘No place. I was in Sonny’s.’

‘Doing what?’ my father interrupted.

‘Nothing. Just hanging around.’

He poked his knife in the air.

‘You spend half you life hanging around with that kid. Ever thought of widening your circle of friends?’

I looked down at my half-eaten lunch.

‘Mum, Sonny’s father gone off some place.’ ‘What do you mean, gone off?’

‘Missing. He’s been gone for a couple of days and left Sonny at home on his own.’

‘Probably better off.’ My dad tapped the side of his plate. ‘His old man’s fucken crazy.’

‘Mum, he’s got no food in the house.’

‘None of our business,’ my father interrupted again.

She opened her mouth to speak. He slapped the table with his hand.

‘None of our business.’

I made it our business later that night when I climbed out of my window, knocked at Sonny’s window and told him I’d made a leftover roast lamb and pickle sandwich for him.

He licked his lips. ‘Where is it, then?’

‘On the top of my dressing table.’

‘Why didn’t you bring it here?’

‘Thought you might like to bunk at my place, seeing as you’re on your own.’

He didn’t want to make out like he was interested and shrugged his shoulders as if he didn’t care one way or the other.

‘Eat here. Or your place. I don’t mind. But what about your old man? I don’t think he likes me.’

‘Means nothing. He don’t like me a lot. Anyway, he’ll be asleep. Can’t keep his eyes open once the sun goes down after he’s been driving.’

He followed me across the roof, through the window and demolished the sandwich in a couple of bites. He sent me downstairs for a second

sandwich. The radio was playing in my parents’ bedroom. My mother would be sitting up in bed, reading a book and humming in tune to the music.

Sonny was a little slower on the second sandwich. He tried saying something but I couldn’t understand him because his mouth was full. He waited until he’d swallowed a mouthful of sandwich and spoke again.

‘What’s the time?’

‘Time. What do want to know the time for?’

‘Cause I’ve got a secret for you.’

‘And what is it?’

‘Tell me the time first.’

I pointed to the clock with the luminous hands, sitting on the mantle above the fireplace.

‘Nearly ten. Now tell me the secret.’

He wiped crumbs and butter from his lips.

‘Same time, every night, I been in the yard watching the upstairs back window of the Reverend’s place. First couple of times it was by accident. Putting the rubbish in the bin when I look up and see this outline against the lace curtain in the room.’

His eyes widened and lit up like he’d just told me he’d found a pot of gold.

‘An outline? What about it?’

‘The outline of that girl, Selina. Side on. I could see her shape. Tits and all.’

‘How’d you know it was her? Could have been the mother.’

‘Bullshit. You had a good look at the mum. She’d have to be twenty stone. No, it was Selina. I seen her there the first night. And the next, when I put out the rubbish again. I been checking in the yard most nights since. And she’s there. Every night.’

I swallowed spit and licked my dry lips.

‘What time is she there?’

‘Just after ten.’

The small hand on the clock was about to touch ten.

‘You think we should go down in the yard and take a look?’

‘Better than that. I reckon we should climb out of this window and cross my roof onto hers. We might be able to see something through her window.’

‘She’ll see us.’

‘No, she won’t. Not if we’re careful.’

I looked over at the window and back to my open door. I walked across the floor, closed it and turned the light out. I nodded toward the window. Sonny opened it, climbed out and crept across his roof onto Selina’s. I followed him, trying as hard as I could not to step on a loose sheet of iron.

We sat under the window getting our breath back. Sonny stuck his finger in the air, turned onto his knees and slowly lifted his head to the window. When I tried kneeling he pushed my head down with his open hand, sat down, leaned across and whispered in my ear.

‘She’s got nothing on but he undies. Come on. Take a look.’

I turned around and slowly lifted my body until my chin was resting on the stone windowsill. Through the holes in the lace I could see into the room. Just like Sonny said, she had nothing on but a pair of white underpants. She had no scarf on her head and her hair sat on her shoulders. Her arms were crossed in front of her breasts. She was crying. And she was shaking. Her whole body.

I felt bad for staring at her and was about to turn away when the bedroom door opened. The Reverend came in, closed the door behind him and said something to her that we couldn’t hear. She turned away from her father and faced the bed. He took off his suit coat, slipped out of his braces, unbuttoned his shirt and took it off. The Reverend’s body was covered in dark hair. He moved closer to her and pushed her in the middle of the back with a giant paw. She landed on the bed, her sad face almost touching the windowpane. Suddenly it went dark and we could see nothing.

We both knew what we’d seen but didn’t know how to talk about it. I made Sonny a bed on the floor with my sleeping bag and spare pillow. I hopped into bed, my guts turning over and over. I couldn’t sleep.

‘You awake, Sonny?’

‘Yep.’

‘What are you thinking about?’

‘Not much. You?’

‘I was thinking about her face. I’ve never seen a look like that before. Never seen anyone so frightened and angry at the same time. Like she

was gonna die. And like she was about to cut someone’s throat.’

When the bedroom door opened I jumped with a fear of my own. My mother was standing in the doorway. She spotted Sonny’s bed on the floor and closed the door behind her.

‘Jesus, Ray. I thought you were talking in your sleep.’ She looked down at Sonny, who’d ducked into the sleeping bag. ‘You warm enough there, Sonny? Can I get you a blanket?’

‘No thanks, Mrs Moore. This is plenty warm.’

She leaned over the bed and looked at my face.

‘What’s up? You look like you’ve seen an ghost?’

I shook my head and answered, ‘nothing,’ without looking her in the eye.

‘Right then. Sleep now, and no chat. You don’t want to be waking you father.’

The next morning she knocked at the door with a spare pair of pyjamas under her arm.

‘Put these on, Sonny, and the two of you come down for breakfast.’

‘What about, dad?’ I asked.

‘Don’t worry about he pyjamas,’ Sonny interrupted. ‘I can climb back out the window here. I’m okay.’

‘You won’t be climbing out any window. You do what I said. Put these on and come down for breakfast.’ She tousled my hair. ‘And don’t worry about your father. He might have the bark, but I’m the only one who bites around here.’

Sonny and me didn’t talk about what we’d seen that night. I couldn’t speak for his feelings, but I knew I was ashamed of what I’d seen, even though I didn’t understand enough of it. I also reckoned that speaking about what we’d seen would be dangerous. I had nightmares about the Reverend turning into an animal, a bear, and other times, a wolf. When I passed him in the street I couldn’t take my eyes of the long hair growing on back of his hands, something I hadn’t noticed before. And if I came across Selina in her front yard I’d look the other way, full of guilt, like I’d done something bad to her myself, which in a way I had.

In the middle of the winter I was walking home from the fish and chip shop one night sharing a warm parcel of potato cakes with vinegar with Sonny when we heard the siren of a fire engine off in the distance. His father had turned up back at home after a week on a bender. He put himself on the wagon and an AA program and hadn’t had a drink since. Kept himself dry but miserable. But at least Sonny was getting a feed and the house was in order.

We turned the corner into the street. The scent of wood smoke was in the air.

‘I love that smell of wood. Means my mum will have the fire going and it ‘ll be cosy in the house. You’re dad put the fire on?’

‘Yep. Since he’s been off the piss, he orders in whole logs and chops the wood in the back yard. Doing his punishment. When he was on the grog he was happy to throw the furniture on the fire.’

I could see people were gathered at the far end of the street, and sparks leaping into the sky somewhere behind Sonny’s place. Or maybe my place. We started running. Sonny’s father was standing on the footpath out the front of his place with his hands on his hips.

‘Is it our joint?’ Sonny screamed.

‘Na. The religious mob next door. In the back stable where all the singing goes on.’

Less than a minute later the Fire Brigade tore into the street, lights flashing. The men jumped out of the truck and ran through The Reverend’s house, into the yard. Another fire engine turned out of the street, parked alongside the back lane. I could hear the old timber of the stable cracking and exploding. Selina was standing outside the house, holding her mother’s hand. She was wearing a crucifix and praying out loud. The Reverend was nowhere to be seen.

By the time the fire was out there was nothing left of the stable. It was burned to the ground, along with everything inside, including the piano, which turned to charcoal, on account of the intense heat. The police had turned up and one of the firemen was explaining to them that they hadn’t been able to get close to the fire until some of the heat had gone out of it.

‘And then we had to break the stable door down. It was heavily padlocked.’

While the copper was taking notes another fireman came out of the house and spoke to his mate.

‘We have a body. A male.’

‘Where?’

‘In the stable. Under a sheet of roof iron and framing. Would have fallen in on him. Got a decent whack in the back of his head’

The policeman looked up from his notebook.

‘I thought you said the door was padlocked from the outside?’

‘It was.’

‘You sure?’

The fireman looked insulted.

‘I know my job. I’m sure.’

Sonny stared at me and I looked across the street at Selina. Her face was as blank as a clean sheet.

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Too Afraid to Cry

by Ali Cobby Eckermann

Ilura Press

Reviewed by SOPHIA BARNES

Ali Cobby Eckermann’s elegant, confident and distinctive memoir is a slim volume for all that it contains. If a reader has the leisure to read it all in one sitting (as I did) the impact of its interwoven vignettes, interspersed with poetry, will be heightened. It is a book which rewards complete engagement and a willingness to follow the sometimes unanticipated shifts in rhythm of its fragmented form. Following the success of several collections of poetry and two verse novels, Too Afraid to Cry brings Cobby Eckermann’s ear for the cadences of memory to sharp, crisp, at times even blunt prose.

Each chapter, identified only by number, is short (the longest only stretch to three or four pages) and these chapters are frequently separated by brief, titled poems. This combination — a kind of verse novel (or verse memoir) in itself — serves to give a reader the sense that they are taking a series of interrupted glances at a tumultuous, changeable and rich life. Cobby Eckermann moves across stretches of time confidently, zooming in on moments of encounter, epiphany or conflict in such a way that we feel irresistibly pulled along with her, piecing together the intervening time through poetry whose loaded imagery is beautifully interwoven with narrative events. Occasionally the poems foreshadow, occasionally they meditate on what has passed (though never in an explicit or heavy-handed way), and together they underpin the rhythmic power which makes this memoir such compelling and affecting read.

Too Afraid to Cry opens with ‘Elfin’, a spare yet lyrical poem whose motifs of song and growth, of flight and emergence, are juxtaposed quite shockingly, but very effectively, with the almost uncannily abrupt scene of child sexual abuse which begins on the page opposite. As readers we know immediately that the territory of this memoir will not be comfortable or easy for us to traverse; yet what I found striking was that even as this horror of violation is bluntly introduced, we hear the young Ali’s voice, loud and clear. ‘Fat chance!’ she thinks, as she endures her Uncle’s fumbling. She may have experienced adult betrayal in the worst imaginable way, yet this young girl is no victim — that much is clear from the very opening, and it’s an impression which only becomes more concrete throughout.

Ali Cobby Eckermann grew up as in indigenous child in an adoptive family. There is real, if often unspoken, love between mother, father and adopted daughter; nonetheless, as Ali grows up she comes to feel more and more an outlier. The abuse to which she is subjected in her school years brings her to consciousness of her difference, and it is a realisation from which she cannot retreat. The tragic irony of the pressure under which she is put to adopt out her own child brings home to the reader the scope of an inter-generational story of dispossession and loss, as well as sacrifice. Along with her ‘Big Brother’, Cobby Eckermann shares the experience of being both familiar and foreign, in indigenous and white Australian society.

Too Afraid to Cry narrates fitful travels through the outback, from town to town, taken in the years of Cobby Eckermann’s early adulthood, and it does so with unswerving honesty — the choices made or not made, the relationships begun and ended, the jobs gained and abandoned. This account of her movement through space, from job to job and finally through rehab to a place of family, creativity and healing is always counterweighted by the timelessness (it is undoubtedly a cliché, yet I can’t help finding it to be true here) which her poetry seems to evoke, or to capture — at the very least, to speak to.

There is the confronting clarity and bluntness of ‘I Tell You True’: I can’t stop drinking, I tell you true / since I watched my daughter perish […] Since I found my sister dead […] Since my mother passed away. Then there is the irresistibly continuity, the extending time of ‘Bird Song’: Life is Extinct / Without bird song / Dream Birds / Arrive at dawn / Message birds / Tap Windows / Guardian birds / Circle the sky / Watcher birds / Sit nearby / Fill my ears / With bird song / I will survive. Cobby Eckermann balances the unadorned prose in which she recounts her memories and her journey without apology or bravado, with the rhythmic undercurrent of her poetry.

As we become more aware of the myriad experiences of dispossession and of broken families which have so defined our colonial history in Australia we might risk a sense of being overwhelmed, of feeling as if we had heard ‘too many’ stories, of being unable to step back and to see afresh the scale of what was done, and to listen to the accounts of those to whom it was done. Ali Cobby Eckermann offers a fresh, unflinching and uncompromising iteration of a search for identity undertaken by multiple generations of adopted and adoptive indigenous children and parents. Yet she does not just tell her story to add to the existing record; she weaves a compelling narrative whose lingering emotion, for this reader, was a vital and entirely beguiling strength. A continued and unashamed pleasure in life, a love for colour and voice and land, sensation, interaction and perhaps above all, language, radiated from this memoir, and I think that stray lines of Cobby Eckermann’s poems will continue to surface in my resting mind for weeks to come.

SOPHIA BARNES is a Postgraduate Teaching Fellow in the Department of English at the University of Sydney, where her Ph.D has recently been conferred. She has published academic work internationally, and has had creative writing published in WetInk Magazine. In 2013 she was shortlisted for the WetInk / CAL Short Story Prize for the second year running.

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

Born in Shanghai, Jamie Wang is an Australian writer currently living in Hong Kong. She holds a master’s degree in business and worked in the field of business analysis before embarking on a writing journey to fulfil her long time passion for literature. As well as writing literary fiction, Jamie creates local art gallery press releases and does volunteering work. She is a member of the Hong Kong Writers Circle. Jamie is currently working on fiction and nonfiction stories and studying literature and arts part time.

Born in Shanghai, Jamie Wang is an Australian writer currently living in Hong Kong. She holds a master’s degree in business and worked in the field of business analysis before embarking on a writing journey to fulfil her long time passion for literature. As well as writing literary fiction, Jamie creates local art gallery press releases and does volunteering work. She is a member of the Hong Kong Writers Circle. Jamie is currently working on fiction and nonfiction stories and studying literature and arts part time.

FUNERAL

My grandfather passed away. He was 85. Died in peace. During his lifetime, he had five children; they all got married, and in turn had seven grandchildren. Sixteen of us, no matter where we were living in the world, all came back to Shanghai on weekend to see him the very last time.

The funeral was scheduled on Sunday, 4 days after my grandfather passed away. I had already been to the wake that my aunty set up. We made the paper money. We burned the incense. We stayed up for 3 days and nights to make sure the white candles at the altar did not go out.

The day my uncle arrived in Shanghai was clear and rainless. I looked through the window and saw him and my cousin get out of the taxi. He insisted on us not picking them up from the airport and went straight to our place after checking in to the hotel.

Tea was served. My mother apologized for not brewing it from fresh green tea leaves. It was almost the end of the year and new tea would be only ready in spring. My uncle sat in the middle of the couch, his arms folded, eyes red and swollen. My cousin was next to him. He grew up so fast. His body looked young and his muscles tightened under the shirt whenever he moved. The last time I saw him was years ago when I was on holiday in Hawaii. We had so much fun. I still have the photo of him snorkeling with all the fish nibbling his butt. I took it while I kept throwing bread to him from the boat. I was disappointed he did not make my wedding a few months ago. He had just started his first job after graduating from Berkeley.

“What happened to Pa?” My uncle sipped the tea and asked, his voice dreary and almost impersonal.

“Father was admitted into the hospital last Saturday; he was stable at first.” My mother went on telling how bad things then followed, how she had rushed to the hospital, how she had seen my grandfather the last time, how my father had cleaned my grandfather’s body. How she had held her grief to inform the relevant people. She would have repeated this so many times, the string of tears fell from her cheek to hands but she just kept talking. I wanted to stop this torture but I was not allowed to. It was her duty; the eldest, to report to the son that everything was properly done while he was away.

“I am the eldest, so I should pay for the biggest portion.”

“I am the eldest, so I shouldn’t let my sisters take the blame.”

She said this to my father and me so often that we got tired.

Sometimes I grew impatient and talked back. “So what, you take all the responsibilities and no one appreciated it. They only came when they needed help.”

This weekend she was not the eldest, as my uncle was there. He was the fourth of the siblings and the only son. My cousin was the son of him, which makes him the grandson. We else were just the third generation, as we did not bear the last name of Zhu.

“Ma, Jay kept talking about Yabuli, apparently Club Med built a new ski resort there. You must know that place right, somewhere in Heilongjiang?” My new husband was a huge snowboarding fan. He chased after the snow instead of sun. I asked my mother because she was sent there when she was 15.

“I had to go. It was the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Chairman Mao didn’t want us to study. He wanted us to go to the countryside to be farmers and learn from them.”

“Why did it have to be you?”

“I am the eldest, if I didn’t go, your aunts and uncle had to. I couldn’t let this happen.”

“Your mother got lucky,” every now and then some aunts would say this to me. “She went to Heilongjiang and got chosen to go to the army university. Then she became a lecturer and got sent to America. Not like us, we stayed in Shanghai, only graduated from high school then went to the factory and got laid off at 40.”

I smiled to them and nodded. I was a good niece.

“It was so cold there, the furthest part of China and bordered with Russia. Most of the time was negative 20 degrees,” my mother always opened her story with the extreme weather condition and geographical remoteness of the place. “If you lick a metal spoon outside the room. It would get stuck and hurt like hell when you tried to take it off.”

“What did you do there?”

“Everything, so long as it was deemed hard that we city people could benefit from doing it. We worked as farmers, as builders, or as anything Chairman Mao set his mind on. There were so many times I had to jump into the dirtiest water up to my waist to clean up the linen even when I got my period.”

“That’s gross.” I frowned, “What did you eat?”

“Potatoes. Stewed potatoes, stir fry potatoes, steamed potatoes, potato wedges, potato chips, whole potatoes, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes. Sometimes we had pork dumplings. Rarely, but that was the best. On those nights, the boys would play chess with the cooks and we girls would sneak into the kitchen to steal as many dumplings as we could, freeze them for the next few months.”

“But I never forgot studying. I smuggled books whenever I could. Oh boy, I could have got into big trouble if they saw the book underneath the red book of Mao.” My mother always finished the story as a good role model.

“Your mum was only 15,” my grandmother told me when I went to her to verify the details of the story, “I still remember the day I sent her to the train station. Your grandfather and I were heartbroken to see our little girl off to that place, so bitter and far away. She stayed there for four years.”

***

She is the eldest.

And he is the son.

She needed to report to him how they had tried their best to look after the old father after the son moved to America 17 years ago.

She needed to take the blame if the son was not happy with his sisters.

She needed to take the scolding from her younger sisters if they didn’t think

she defended them enough.

I sat at the other side of the room, watching.

A girl, an only child, an outsider.

I was the apple of my uncle’s eyes as he brought me up. But I was not allowed to participate in the discussion even though I was the eldest grandchild and I was 32. My little cousin was there, palms on his knee and silent. I wanted to take him away, cover his ears. He was tired, just had 16 hours flying and had to fly back in 3 days. He was too young to be involved. But I was not allowed to. He was the son of the only son. That qualified him.

The tea was getting cold and so was I. I almost forgot how cold Shanghai was in the middle of the winter. I had left so long, came back so little that some old friends of my grandfather no longer recognized me.

But I remembered. Once I was here, my body would carry me of its own accord, sit, talk and eat the way I was supposed to sit, talk and eat.

Deep fried Chinese doughnuts and sweetened soymilk. Jay opened his eyes wide when he saw me swallowing these down without a fuss.

“Guess someone is not allergic to deep fried food and white sugar anymore,” he said this to himself giving me a wink.

Or perhaps I hadn’t changed, perhaps this was the real me with my roots.

No one can be exempt from their birth place. Not even my cousin, who left Shanghai at a tender age of five

The funeral started.

“Let us share five of our favorite stories of our father,” said my uncle. “I’ll share mine first. When I was born, my father got a call from the hospital notifying him the news. He didn’t ask if my mother was okay, he just asked was it a boy or a girl? Once he heard the baby was a boy he left work immediately, went to the shop, bought a pram, and went to the hospital. This had never happened to any of my elder sisters and would not happen to my younger sister later when she was born.”

My mother was crying, the eldest. She told her story; the loving father magically multiplied the dumplings in her bowl by eating none himself.

My aunts were crying, the sisters. They told their stories. A kind father picked up his daughter from the work place every day for years until she married because she finished work after midnight. Later she was picked up by the husband.

Then another story plus another story.

Bow three times.

On your knees, bow three times.

The last prayer, bow another three times.

My mother stood there in black with a white flower in her hair, looked even smaller than the rest. She was the eldest, but the shortest among all the siblings, 160 cm as opposed to average 170 of all my aunts. Zhu’s family were very proud of their height.

“It must be because we sent her to that god damn place when she was still growing.” My grandmother always said this whenever someone mocked my mother’s height.

“Does he have any grandsons?” asked the officer from the funeral place.

I was silent, along with another 5 of us. We knew he was not asking about us.

“I am.” My cousin raised his hand.

“Well, you need to hammer the last nail to seal the coffin.”

The coffin was dark red, solid wood.

Done.

“Well, you need to take the picture of your grandfather and lead the procession.”

Here we were, 16 of us, the son, the eldest, the sisters, the third generation along with the others, following the grandson to walk the last part of the journey of my grandfather.

The funeral was over.

The ceremony would then last 49 days. The prayers would be sung by the monks in the temple every seven days. I was secretly glad that Jay and my cousin would have left by then. Their nostrils were not used to the smell of the burning incense. They sneezed crazily after staying in the room for a while.

The echoes of their sneezes were immediately swallowed by this city. The city of the grandfather. The city of the eldest. The city of the son. The city of the family.”

November 25, 2013 / mascara / 0 Comments

When My Brother was an Aztec

When My Brother was an Aztec

By Natalie Diaz

Copper Canyon Press

ISBN 9781556593833

Reviewed by AIMEE A. NORTON

Natalie Diaz’s debut collection is a book about appetites. It contains raw, narrative poems that pivot on her brother’s meth addiction. Lyric surrealism is interspersed throughout and serves both as a welcome reprieve from the brutality of the narrative, but also expertly explores the universal hunger that brings people to their own personal tables of conflict and gluttony. The setting is the Mojave Indian Reservation where Diaz grew up and where she currently works with the last fluent speakers of Mojave to save the severely endangered language.

Diaz’s poems grind with a savagery that doesn’t often make it onto the page. The Aztecs are a culture known for ritualized violence and a theater of terror epitomized by state-organized human sacrifice. Diaz does well to sew the Aztecs together with drug culture in the Southwestern US which is an area saturated with narcotics related violence. Addiction itself is shown as a ritualized self-violence. The title poem ‘When My Brother Was an Aztec’ begins hauntingly.

He lived in our basement and sacrificed my parents

Every morning. It was awful. Unforgivable. But they kept coming

back for more. They loved him, was all they could say.

The poem ends just as hauntingly when Diaz describes her parents searching for their missing limbs, looking for their fingers…

To pry, to climb out of whatever dark belly my brother, the Aztec

their son, had fed them to.

Readers witness the violence of meth addiction, see the blackened spoons and the sores on her brother’s lips, hear the tribal cops outside on the lawn, understand from the poem titled ‘As a Consequence of My Brother Stealing All the Light Bulbs’ that her parents live without light. The tone is unapologetic and fierce. It is unblinking on a topic that breaks many families. Yet a close read reveals unmistakable joy in the writing. Diaz celebrates that language can express these truths, even if they are hard truths. The poems are alive on the page, delivered with a skill that often hides underneath the intensity of the material.

The characters devour, feed, starve, gorge, thirst and more. In the poem ‘Cloud Watching’, Diaz writes “So, when the cavalry came, / we ate their horses. Then, unfortunately, our bellies were filled / with bullet holes.” In ‘Soiree Fantastique’, her brother sets a table for a party attended by Houdini, Jesus, Antigone and others. It ends when the poet explains to a distressed Antigone “We aren’t here to eat, we are being eaten. / Come, pretty girl, let us devour our lives.” The effect of all this devouring on the reader is that it makes one insatiable for more of Diaz’s poems.

There are three parts to the book. The first section serves as an introduction to life on the reservation. We meet ‘A Woman with No Legs’ who “curses in Mojave some mornings Prays in English most nights Told me to keep my eyes open for the white man named Diabetes who is out there somewhere carrying her legs in red biohazard bags”. We visit a jalopy bar called ‘The Injun That Could’. We learn of a literal dismantling of the Hopi culture when a road is cut through Arizona in ‘The Facts of Art’. This section feels more historical and cultural than personal. For the lovers of form, Diaz scatters a Ghazal, a Pantoum, an Abcedarian, a list poem and prose poems throughout the collection.

The third section contains a handful of love and lust poems such as Monday Aubade:

to shut my eyes one more night

On the delta of shadows

between your shoulder blades –

mysterious wings tethered inside

the pale cage of your body – run through

by Lorca’s horn of moonlight,

strange unicorn loose along the dim streets

separating our skins;

The surrealism persists in the love poems. Often, the act of loving is portrayed as a kind of sacrifice. The answer to the poem titled ‘When the Beloved Asks, ‘What Would You Do if you Woke Up and I Was a Shark?’ ‘ is clear: “I’d place my head onto that dark alter of jaws” and “it would be no different from what I do each day – voyaging the salt-sharp sea of your body”. It’s obvious that Lorca has been a substantial influence on Diaz. She places a passionate poem titled ‘Lorca’s Red Dresses’ smack in the middle of the third section as well as mentioning him in ‘Monday Aubade’ and other poems.

The engine of the book is the second section. These poems cast and recast the brother as various characters: a Judas effigy, an Aztec, a Gethsemane, a bad king, a lost fucked-up Magus, a zoo of imaginary beings, a Huitzilopochtli (a half-man half-hummingbird god) and various characters from myth. The theme of the book is being present in the face of a powerful destroyer, or living through an encounter with the destroyer, witnessing the wreckage and not turning away. Ruin is wrought by her brother’s meth addiction. There’s a reach to her talent that challenges the importance of her work being limited by identity. I read a few of her poems to Plath’s ghost saying, “Look here, you aren’t the only one that can plate up mouthwatering, award-winning anger for male relatives”.

Destruction of Native American culture by Europeans settlers and the continued, historical bigotry is featured in the poems. Ships appear throughout the book as harmful things. Take the wonderfully-titled poem ‘If Eve Side-Stealer & Mary Busted-Chest Ruled the World’ which is an alternative retelling of first people and creation, the last stanza reads:

What if the world was an Indian

whose head & back were flat from being strapped

to a cradleboard as a baby & when she slept

she had nightmares lit up by yellow-haired men & ships

scraping anchors in her throat? What if she wailed

all night while great waves rose up carrying the fleets

across her flat back, over the edge of the flat world?

I struggled with the question in this poem: what if? Diaz refuses to answer it. The mind still asks: What if we erase just this one chapter where the Hopi’s burial sites are dug up for a new road? Or, what if a daughter is not stoned to death? What if Diaz’s brother had not gone to war and had not crawled into bed with death? Diaz knows this can not be. It is as likely as the world being flat. Her answer is a refusal to see anything other than the violent, beautiful world we have that is full of lightning. This is a brave approach. Yes, destruction is also generative. If there was an end to violence, then nothing new could be born.

Still, I wonder whether the perspective and tone in When My Brother Was an Aztec, which is in part the powerful backstory of Diaz’s life, will shift now that this fearless narrative is spoken. I predict that the book breaks open a future to be found in Diaz’s not-yet-written poems to show what a world would look like if she were the boss goddess. One truth is: the future exists. Another truth is: we get to help shape it. I confess that I read utopian science-fiction, so I know that Diaz has exactly the kind of brutally honest mind that should broker destiny by introducing a few options and answering that question: what if Eve Side-Stealer and Mary Busted-Chest ruled the world? I still want to know. I’m hoping her second book tells me. Diaz signed my copy of this book with “sumach ahotk” which is Mojave for “dream well”. Yes, let’s dream well.